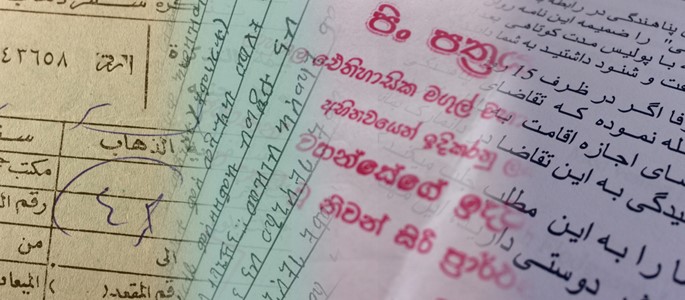

Interpretation in asylum cases 2:2/ Practical experience and examples

An interpreter and a case worker share their experience, and a number of examples illustrate the extent of the problem

Read more in our first article about translation in asylum cases: Facts concerning legislation and standards.

To let them speak freely, we made both the interpreter X and the case worker Z appear anonymously here. The examples have been collected from many sources, which you will find at the end of the article, where you can also see the recommendations from Refugees Welcome on this subject.

Case worker Z:

Z held a job for several years as a clerk and a case worker at the Danish Immigration Service asylum department, but today Z has another job. Z also happens to speak one of the languages which is the mother tongue of many asylum seekers.

Z experienced interviews that had to be cancelled because the interpreter and the asylum seeker did not understand each other. The main issue is often with different dialects of Arabic, where the differences can be very significant. According to Z it’s a problem that Afghan interpreters (Dari) are often being used to translate for Iranians (Farsi) and vice versa. Though the two will normally be able to understand each other, they will use very different words and expressions. If you had a Farsi interpreter during your first interview and a Dari interpreter for the second, it may appear as if the applicant changed his explanation, and for this reason can be found not credible.

Examples of words which have been translated incorrectly:

“armed soldiers” translated to “men” (Somali)

“sick” translated to “leave” (Russian)

“brother-in-law” translated to “brother” (Dari) (source D)

Example of a wrong translation which changed the meaning of the sentence:

An asylum seeker said that he had lived close to the Ibn Hanifah mosque. The interpreter translated this to mean that he had been a follower of the Islamic school Ibn Hanifah, which is a fanatic Islamic party (source D).

If an asylum seeker is not feeling comfortable with the interpreter, it is according to Z very hard to make a complaint or to ask for another interpreter. A complaint can lead to several months of extra waiting time. There is also no balance in the power between the parties, as the asylum seeker sees the case worker and the interpreter as part of the authorities (which is true). Many asylum seekers are afraid that a complaint or any kind of discontent will harm your chances of getting asylum (which is not true). Finally, there is time pressure on both interpreter and case worker to get the interviews done within a certain number of hours.

Example of a case where the applicant was not feeling confident with the interpreter, but was afraid of the consequences of a complaint:

A female asylum seeker from Syria tells that her interpreter at Immigration Service had Bashar Al Assad as a cover picture on his smartphone. During the break he asked her about her family and assured her that there was no reason to flee from their area. Her daughter and son were at that time both held in a prison in Syria, and she was terrified that the interview might harm them. For that reason, she said almost nothing during the interview and got a rejection. Later she was granted asylum in the Refugee Appeals Board. (source D)

Z was working for Immigration Service during the large number of arrivals in Denmark 2016, and Z found that anybody could be hired as an interpreter at that time. This did not only affect the lingual level, but also caused ethical problems. E.g. one time when Z overheard an interpreter making fun of a homosexual person during a break.

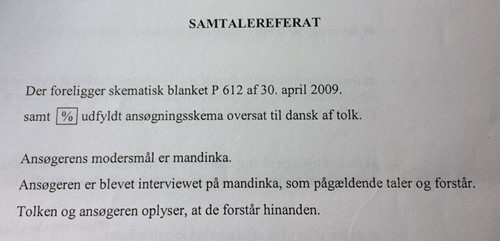

Example of missing interpreter:

An elderly lady from Eritrea has during her years in the asylum system picked up a handful of English words to make herself somewhat understood. However, it is not possible to have a real conversation with her in English. At several meetings with the police about cooperation and return it has been noted in her files:

”The conversation was done in English, which the applicant understands.” (source F)

Z recommends that all interviews should be recorded and filed by the authorities together with the written summary. As long as this is not being done, Z urges asylum seekers to make their own audio recordings on a smartphone (not secretly, but openly – you’re allowed to do it). This has two advantages: Firstly, both interpreter and case worker will be more aware of speaking politely, translate correctly etc. Secondly, it will be possible to prove misunderstandings later through another interpreter.

In Z’s opinion, all interpreters with less than 10 years of experience should go through a special training and certificate program. The interviews with Immigration Service will determine the future of the applicants, and great weight is put on single sentences, words and descriptions – this is used to assess the credibility. Therefore, the quality of translation is essential.

Mandinka is one of the 20 languages spoken in Gambia, a country of only 1.9 mio inhabitants.

Interpreter X:

X has worked for many years as an interpreter in Tigrigna and Amharic, spoken in Eritrea and Ethiopia, both mother tongue languages of X. X has another education from Denmark, but works now as a self-employed translator within asylum and court cases.

According to X, the skill level of interpreters in Denmark is unacceptably low, and only 10% would live up to serious requirements on ethical or linguistic skills. As an example, X has been asked by a countryman to explain the contents of a letter he received from his municipality – and this person was himself working as an interpreter. X also mentions a municipality where they hire newly arrived refugees, still under the integration program, as interpreters for other refugees in the same municipality.

Example of a wrong translation leading to a serious situation:

A young boy under 18 was asked during his asylum interview through an interpreter whether he saw himself as “a fool”? He was so offended that he left the room and stopped the interview. Another interpreter found out that the word “mature” had been misunderstood by the inexperienced interpreter, and the interview could be continued. (source G)

X has witnessed several times that interviews have been stopped because the interpreter was too bad. But afterwards the same interpreter has been booked again for other interviews.

In general, X finds that the standard is lowest at the municipalities, in the health sector, and with the police. Immigration Service and the court system have somewhat higher demands and make sure to block the worst ones. X finds that the highest standards and most professional way to work with interpreters is at the Refugee Appeals Board.

Examples of lacking requirements for the linguistic level:

“The applicant read aloud from the attached forms in fluent Turkish (the writer does not know about Turkish, however, but it sounded smooth and effortless).”

Quote from a police department, assessing an application to be approved to work as an interpreter (source A)

“The interpreter is not able to translate special, professional terms, e.g. Christian concepts or job descriptions within military or police. Therefore, translation takes a long time, the interpreter has to look up words (…).” From case worker about an asylum interview. (source A)

A patient had been tested HIV positive, and it had been translated as a good – ‘positive’ – news, so the patient thought he was safe and sound. (source C)

X mentions a serious problem during the asylum interviews with Immigration Service. When the interview ends, the written summary made by the case worker is translated orally from Danish to the asylum seeker. Each page is signed by the asylum seeker as correctly understood, sometimes with minor corrections added. According to X, this should be done by another interpreter, as this procedure is not a guarantee in any way – a misunderstood word will be repeated in the wrong meaning, as it is done by the same interpreter. The Refugee Appeals Board refuses to consider any kind of translation errors because the asylum seeker signed the summary as correct – this signature should be given less significance, and an audio recording could disclose any misunderstandings.

Example of this:

During the interview, an asylum seeker used an Arabic word in the meaning “unauthorized” about a document. It was translated to “fake” which the word can also mean. When the interpreter reads up the summary at the end, he uses the same word in Arabic – so the asylum seeker will not know that there was a misunderstanding (source H)

Example of a case where the translation was crucial to the outcome:

In 2015, a number of Eritreans were rejected by Danish Immigration Service with reference to the exclusion clauses of the Refugee Convention. They were found to be responsible for human rights violations, and therefore excluded from asylum. The persons concerned had told how they, as part of their forced military service, had worked as a kind of guards at a prison. If translated to “security guard” it means a job ranking above the police and with a great personal power. But correctly translated it was actually just a gate keeper, which is a person letting vehicles in and out of the area who has no personal authority (“sikkerhedsvagt” / “portvagt” in Danish). In the Refugee Appeals Board this was clarified by lawyers and good interpreters, and all the persons in question were granted asylum.

X recommends that an education and a professional evaluation of an interpreter’s skills should be introduced. X took the 1-day course which exists now and finds it totally ridiculous. X also recommends that asylum interviews are recorded in an audio file which can be checked later. Actually, X always imagines that the translation sessions are being recorded – in that way, it’s easier to keep the professional attitude.

According to X, an interpreter must be able to translate correctly and precisely, but you also have to choose the right expression and metaphor, depending on the context, and this requires a deep understanding of the culture of both languages. A perfect interpreter is like an invisible tube between the two persons – they should communicate as freely as possible, and at best almost forget that the interpreter is there. As an interpreter you have to choose words and expressions as close to the original as possible, for instance you can’t eliminate a swearword or correct something that you know to be actually wrong. The only exception to the neutral behaviour is when a person is telling about a rape or other serious abuse which are very hard to talk about – then, a good interpreter must show sympathy and empathy in order to make the person feel safe.

Examples of problems with the interpreter’s own opinion:

An interpreter refused to translate swearwords and rough expressions in a court room, and the court meeting had to be cancelled and rescheduled with another interpreter. (source G)

One of the working Iranian interpreters has a son who is a mullah and travels back and forth between Denmark and Iran. This interpreter might one day be asked to translate for a homosexual or a convert. (source F)

An interpreter was fired because she refused to translate a conversation between a doctor and a woman who was about to have an abortion. This was in conflict with her own Catholic faith. (source E)

Example of unethical use of children as interpreters:

“The patient speaks poorly Danish, but his daughters speak Danish well.” (2 daughters translate for their father about erection problems and blood in his semen). (source C)

Carina Graversen from the Danish Translators Organisation share the views of X. At Folkemødet 2017 she was explaining that interpreters without education are a problem for both asylum seekers, patients and others who are not getting the correct information, and who are themselves being misunderstood. But it is also a problem for all the highly educated and skilled people in the public service who are not allowed to use their competences without proper translation. Read the fact sheet from the Danish Translators Organisation (in Danish).

What does Refugees Welcome recommend?

DANISH PARLIAMENT:

- Examination and certification of experienced as well as future interpreters at different levels, courses in subject-specific terminology and a short basis education in ethics and techniques.

- Publicly available lists of interpreters and their abilities and a gradually introduced requirement that the authorities may only use interpreters with the necessary approval.

- The establishment of a state-recognised interpreter education with different levels of examination, supported by the state education grant.

- Audio recordings of all interviews should be filed.

- Extra focus on not using children as interpreters in the health sector, municipalities, lawyers or in asylum centres.

ASYLUM SEEKERS:

- Stop the interview if you experience any kind of problems with the interpreter's language skills or ethical behaviour. The asylum case is more important than extra waiting time.

- Make audio recordings of your interviews on your smartphone (openly, you're allowed to do it).

- If you are fluent in English or French, insist on using this language in the asylum form and the interviews. Interpreters in those languages are competent and have no connection to your home country, and many case workers understand these languages themselves.

Sources for quotes:

A) Report from Danish National Audit Office, March 2018

B) Lawyer Marianne Vølund, master thesis 2000

C) Morten Sodemann, Indvandrermedicinsk Klinik

D) Article about interpreters in New Times, Sept. 2013

E) Doctor with Iranian roots

F) Refugees Welcome, from the counseling

G) Interpreter X

H) Professor in law Eva Smith: Asyl i Norden, 1990