Danish Immigration Service in conflict with human rights conventions

The Paradigm Shift exposes refugees to unnecessary stress, abuses public resources and serves no purpose

In November 2022, the Refugee Appeals Board put its foot down in a decision on a young Somali, rounding off with a direct message to Immigration Service: the board finds it "somewhat difficult to argue for" revoking the residence permit in view of Danish law, and finds a revoking to be "obviously" in violation of international conventions.

But first, try to put yourself in the young man's place. Imagine that you came to Denmark 14 years ago, and you had a residence permit for 11 years. You get up and go to work with your colleagues, you speak and write Danish all day, you listen to the news on Danish radio. Your closest friends' names could be Marie and Jesper, and you granted a woman called Birthe the role as your mom – having lost contact with your real mom years ago.

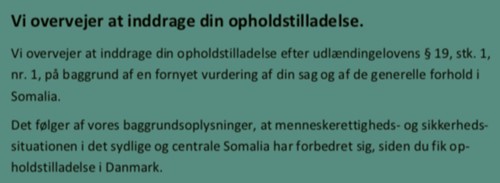

Suddenly you get a letter from Immigration Service in your digital mailbox, along with payslips and notices about interest rates from the bank. You think it might be a reply to your application for permanent residency. But it says: "We consider not to extend your residence permit". You tried this before, 4 years ago. It feels like a nightmare. Back then, things worked out after a long struggle, but then why are they writing again? Your heart races, you get dizzy and feel like vomiting, thousand thoughts start flowing through your brain day and night. Back to Somalia, where you haven't been since you were a teenager? You don't know one person there. Where should you stay, how will you survive? Can you ever come back to Denmark, which is your home, and where you have your whole life?

You keep repeating to yourself: But I have done everything you expected from me! I learned Danish, I have friends and network, I took an education, I work more than fulltime. Denmark shaped me, I belong here now. Can I never get peace to make a future for myself? Do I have to lose everything once again, and start all over again, alone in a strange country? I can never go back to my place of birth, it's too dangerous.

I have done everything you expected from me!

You call Immigration Service and ask what will happen now. They say you will be called in for an interview. Just like the first time, several months pass by, where you have a hard time seeping or concentrating. The interview takes three hours and the questions are exactly the same as last time: what's your problem in Somalia, how is your life in Denmark and your family relations? Two weeks later you get a letter: "Immigration Service will not extend your residence permit." But things went well, there was no use for the interpreter, the lady was friendly? You know you have second chance at the Refugee Appeals Board, but that's a long way ahead.

You struggle to go to work, even if you're totally beside yourself. Your boss calls you in – she also received a letter from Immigration, and she understands it as if it will be illegal for her to have you employed! You break down and think that now it's all over, how will you even pay your rent now?

Thankfully it's a misunderstanding as the letter is very ambiguous, so you keep your job. Another 7 months pass by before you go to the Refugee Appeals Board. And once again you're lucky: you have a good contact who asked one of the best lawyers in the country to take your case. You didn't sleep the night before, and you feel very nervous, even if you just have to answer questions about your job, your friends and family. Luckily it turns out well, as it did 4 years ago. The judge agrees that you belong here in Denmark, now you can breathe again. But will it happen again? And what was the point of it all?

Paradigm Shift and attachment

Before 2015, refugees in Denmark would generally not need to worry about losing their residence permit, which would sooner or later turn into permanent. This is still the situation in most of Europe where the majority of countries will grant temporary stay for 5 years and then turn it into permanent, and most refugees obtain citizenship within the first 10 years.

But today the situation is very different. The first big step was taken in 2015, with the very temporary status due to general conditions under article 7(3), and the net one was in 2019 with the passing of the so-called paradigm shift, changing the criteria for attachment, extension and revoking. Those refugees granted a stay because of general conditions in their country of origin must have their permit reviewed every second year, and it will only be extended if even the slightest improvement has not occurred. Usually, the opposite principle is used, as the UN Refugee Convention requires “durable and stable” improvements to revoke a refugee’s residence permit.

However, Denmark does not regard refugees without an individual asylum motive as “real” refugees, and therefore making a different assessment of possible return. UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, strongly disagrees with the perception from the Danish government. In November 2022, the Stockholm office wrote (again) to Denmark that our 3 kinds of asylum status should be aligned, that all refugees should be granted 5 years stay and that access to permanent residency should be considerably eased. And very specifically, that Denmark should refrain from the mandatory re-assessments of the residence grounds.Danish Insitutte for Human Rights wrote a report about the legal challenges of revoking refugees's residence permits: "Man kan aldrig føle sig sikker".

Somalis and Syrians

Re-assessment of the general conditions in the country of origin has so far led to two waves of revoking (the technical term is often ‘denial of extension’ but in practice the same thing). Firstly, it was the group of Somalis who were granted residence in 2012. Between 2017 and 2018, 1,350 Somali refugees and their family members lost their permit to stay from Immigration Service – when considering their attachment to Denmark, 5-6 years was not sufficient. Even though 50% got their permit back from the Refugee Appeals Board, many left Denmark without waiting for that – some were granted residence in other countries.

Next wave, it was the Syrians’ turn, and that got much more attention. Around 1,200 cases were scrutinized, and two out of three actually got a better kind of status due to an individual asylum motive. But more than 600 lost their permits and had to pass through the Refugee Appeals Board. Here, the percentage of overturned decisions rose from 50 to 80 during 2021 and 2022. In the end, it was just a question of time until they got their permit back, as any public criticism of the Assad regime was enough to get a new asylum motive. But during the waiting time you had to put up with living in the deportation camps and putting education and job on hold, and especially young women find themselves in that situation.

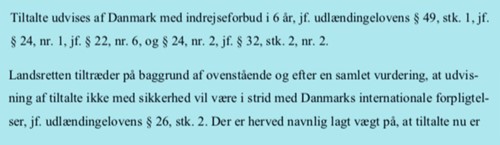

Simultaneously, automatic expulsion takes place whenever a foreigner receives any criminal sentence in Denmark, even conditional. This leads to any sentenced person losing their residence permit at least for a while, and must move to a deportation centre, even if in many cases they will get the permit back when their attachment is assessed in comparison to the seriousness of the crime in the light of the human rights conventions.

Other nationalities

Besides the Somalis and the Syrians who got their permits due to general conditions in their home countries, revoking and withdrawal – or the threat of it – also targets many refugees with individual asylum motives. It could be if Immigration Service receives an anonymous tip from someone who wishes to harm that person, or if a suspicion arises that there was some fraud concerning the identity. Usually, the suspicion turns out to be groundless, but the slow case processing leads to many months of fear and anxiety, not even knowing what the case is about. When asking Immigration Service why they stress people for no reason by sending letters many months before calling them in for interview, they reply that they have a legal obligation to inform the person.

Aida from Iran was granted asylum due to personal persecution, and she educated herself as a social worker. "After 6 years residence permit, I suddenly received a letter that I should come to interview with Immigration Service – they had new information in my asylum case, and they considered revoking it. I went into shock, I couldn't sleep or eat. Several months passed before the interview, and afterwards also a long time before they told me it was okay after all. It was a terrible period; every second I was thinking about what to do – I could not go back to Iran. I had to postpone an exam, I was not capable of doing anything."

I went into shock,

I couldn't sleep or eat

Frank from Uganda was granted asylum due to political threats more than 10 years ago, and later his son joined him. "I got a letter from Immigration Service in August 2021, saying they had new information in my case, and would call me in for an interview. It said nothing about this new information. I got extremely scared, especially because my son has been living here so many years now, he is 15 years old, I can't send him back now. I didn't want o s care him, so I didn't tell him how serious it was – but he could see how bad I felt, and he had also heard about others who lost their permit to stay. It took 5 months before I came to interview – and there they told me that a person from my home country had given them fake information about me. Almost 3 months went by before I got the answer. Luckily, they believed me and let me stay. They could also see that I was well integrated. I work in a nursing home and I'm educating myself on the side. But it was a horrible time, pure torture."

Waste of resources

Earlier on, a residence permit as a refugee or for family reunification would not expire until after 5-7 years, and the extension was more or less automatic – the caseworker just needed to check that there was nothing speaking against an extension. Today, all permits expire after only two years, and they have to be scrutinized with the opposite intension: is there any chance of revoking? Of course, it puts a heavy workload on the caseworkers at Immigration Service.

But the new practice also creates large and unnecessary expenses in several areas. An interview with Immigration Service can take a whole day, and an interpreter is almost always called in. If the case continues to the Refugee Appeals Board, the state pays for the secretariat and fees to the lawyer and the three board members, and an employee from Immigration Service is also present. A number of cases are returned by the Board, which means sent back to Immigration for another review, obviously generating more salary expenses.

If you are sentenced to expulsion, you lose the right to work, study or receive benefits, and you must leave your accommodation while staying at deportation centre – it usually takes 6-8 months until the case comes to the Refugee Appeals Board. Staying at Kærshovedgård costs the state 300,000 dkr per year: much more than a person on social benefits which only amounts to 60,000 per year after taxes. And in many cases, we are talking about a lost income to the state and to society if that person was working. When you get your residence permit back, you have to find a new place to stay and start all over again.

Human costs

The economic and societal costs are bad enough, but the human ones are far worse. Refugees are now living day in and day out in uncertainty about whether their future is in Denmark or not. They are now always scared to lose the security and safety which they finally achieved after deeply traumatic experiences and a life-threatening journey to come here. They have painstakingly built a new life in a strange country, but they risk that their very foundation is pulled away from under them again. Their children go to Danish schools and kindergartens but have no guarantee to stay. Families are split up because they have different kinds of residence permits, even if they might have arrived together. Young women lose their permits while their parents and brothers get to stay. Mothers lose their permits when their children turn 18.

A growing number of refugees and migrants live in Denmark on a temporary paper, many thousands are even born and raised here, making Denmark their actual home country. The criteria for permanent residency and citizenship have been heightened again and again. Education and part-time jobs do not count, and even a conditional sentence can exclude you forever.

Barrier for integration

On the long run, both researchers, employers, municipal caseworkers and not least the refugees themselves warn that this policy will have a negative effect on integration, and that refugees' mental health, which is already fragile due to trauma, will deteriorate. Where is the incitement to learn Danish, get an education, provide for yourself, save up for old age, raise your children in Danish culture – if you can any day end up in deportation centre or on a plane to a war-torn country that you left many years ago?

During an interview with Immigration Service, carried out in Danish, a young man is quoted for the following:

"X would like to add that he hopes to have his residence permit extended, as he is very fond of Denmark, Denmark having helped him and developed his competencies which he wishes to make use of in Denmark. For this he is very grateful. He is very sad that his permit has to be reviewed again, as he feels he has done a lot to integrate into Danish society, and therefore he wishes to stay in Denmark so that he can contribute to Danish society with the resources that he has achieved here. X states that he feels himself to be Danish and that Denmark is his home today."

The eagerness of Immigration Service

As ministers for integration, both Inger Støjberg and Mattias Tesfaye gave orders to Immigration Service to revoke as many permits as possible, as long as international conventions were not violated. Immigration Service, willing to serve, revokes one too many rather than one too few, and even produces their own country of origin-reports, which sources have later distanced themselves from and criticized for being biased. On the other hand, the latest of their own reports describes a serious and arbitrary risk for any returned Syrian to face abuse, which has however not led the asylum office to stop revoking permits.

But in fact, we don´t know where the limit goes when it comes to the conventions. No other countries than Denmark would dream of revoking the permit to a refugee who has been here for many years, behaves nicely, even pays taxes and carry out a specialized job which is in high demand. International practice only exists in relation to expulsion for crime or fraud.

In the comments to the law package called the Paradigm Shift, the civil servants from the ministry admit that nobody knows how the European Court of Human Rights look upon revoking a residence permit to a refugee if that person has done nothing wrong:

"There seems to be no practice from ECHR concerning the situation where a residence permit to a person who was granted asylum in that country has lost that permit due to conditions which led to the permit have changes so that the person is no longer at risk."

The Refugee Appeals Board directly criticizes Immigration Service for going too far in their recent decision concerning the Somali man mentioned at the beginning of this article. Immigration Service took away his permit not just once but twice, but both times he got it back from the Refugee Appeals Board due to strong attachment and good integration:

"After a consideration of the situation as a whole, the Refugee Appeals Board finds that it would very clearly be in violation of ECHR article 8 to deny an extension of the claimant's residence permit in Denmark. (…) The Refugee Appeals Board finds reason to make a general comment that in a situation such as this – where the Board in the spring of 2018 made a decision that a revoking of the claimant's residence permit would be particularly burdensome according to Danish Alien Act art. 26 (1) and where the following [more than four and a half year] have been no "negative" changes in the claimant's personal situation including namely his job– or integration related conditions – it would seem somewhat difficult to argue that a denial of extension of the claimant's residence permit in Denmark would not be in violation of art. 8 of ECHR." See the whole decision on fln.dk under Praksis: Soma/2022/44/mima

There is also the fact that Immigration take the initiative to send a letter to a person's employer with a wording which is totally impossible for that employer to interpret, and which can only lead to groundless layoffs and thereby harm the person further: a break in the employment history will destroy a person´s chances of obtaining permanent residence permit later. Immigration writes this to an employer:

"X (…) has received a decision from us which may mean that he person in question will lose his permission to work in Denmark. (…) We cannot inform further about the decision we have made, as it contains personal information. (…) We hereby inform you that if the person in question is a refugee and had his residence permit revoked or denied extension the case will automatically be appealed to the Refugee Appeal Board. The person in question will have the right to stay and work in Denmark until the Refugee Appeals Board has decided on the case. In case the person in question is a refugee and the residence permit has lapsed, there is no automatic appeal and the person in question will not have the right to work. (…)"

One may wonder why a public office which is supposed to be neutral, is so eager to pursue a political agenda. Human considerations might be too much to expect, but Immigration's practice goes against international law, good administration standard and reasonable use of limited resources. And it contributes very much to producing what some politicians have started naming "crazy cases" – where one could expect a more flexible case handling and professionally funded warnings to governments when their restrictive legislation goes too far.

You read the article for free.

Become a member or make a donation

to keep us running!