European asylum-colonialism? / Martin Lemberg-Pedersen

The EU paid Gaddafi millions of euro to keep refugees away from Europe – and the idea of establishing refugee camps outside of the EU has also been heard before

During just one week in April 2015, more than 1,300 boat refugees drowned near the Libyan coast when two ships sank. The majority of them had fled from the brutal civil war in Syria, the oppressive regime in Eritrea, the failing state of Somalia, and, Afghanistan, which during the last decade has continually topped the list of countries generating the greatest amount of refugees. The Syrian conflict has produced 8 million internally displaced Syrians and over 4 million are displaced abroad. Until now, the majority of the externally displaced Syrians had remained within neighbouring countries, and countries such as Turkey (2 million), Lebanon (2 million) and Jordan (800,000) have shouldered an incredible responsibility but have since begun to close their borders again. Since Gaddafi’s fall, Libya, where many people had travelled to in order to find work, is falling into chaos. The refugees’ neighbouring countries are either unstable or reaching maximum capacity.

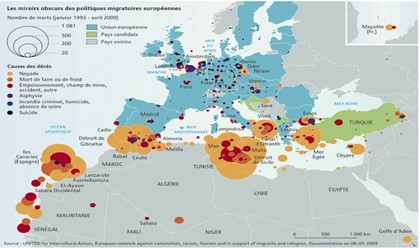

These factors help to explain why the number of boat refugees has risen during 2015. If it continues with the same pace, 2015 will end as a year record numbers undertaking the exodus towards the EU from the Middle East and Africa. And as the rate of exodus increases, so too does the death rate: the number of deaths in 2015 is already nearing 2,000, compared with 3,500 for all of 2014. Since 1993, over 22,000 people have lost their lives at the borders of the EU, the majority within recent years. In other words, people are so desperate, that they are willing to take the ultimate chance and pay human-smugglers for the boat trip to Europe.

New words, same old tune

Following the tragedies in April, first, the EU’s Foreign Ministers met and agreed upon a ten-point plan, then the Ministers of the Interior and Ministers for Justice, which culminated in a common plan. This plan though, was just new words sung to the same old tune: reinforcing border control, tackling the smugglers, concerted planning and action in terms of the EU’s political and military efforts, establishment of a large deportation programme and efforts at co-operation with a third-party country. In all honesty, there’s not a single one of these proposals that isn’t already EU policy. Even more absurd – within the last 15 years, the majority of these proposals have already been hailed by both Danish and European politicians as solutions to refugee crises.

The Commission did, however, emphasis some ideas that contain the seed of more forward-looking solutions, although they have already been presented in the past; namely, an acute redistribution plan internally within the EU and a pilot project with resettlement of refugees from neighbouring countries. Other voices also underlined that re-opening the possibility of seeking asylum from the EU countries’ embassies and consulates would undermine the people smuggling market. Many member states dismissed these ideas immediately, leading to the continuation of a decade-long conflict between the EU Commission and the Justice and Home Affairs Council: the Commission has long supported the idea of redistribution, while the Council – comprised of national ministers – expresses shock at the prospect of more refugees and has instead decided to tackler smugglers and so-called illegal immigration. And of course, the then Danish Prime Minister, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, used the Danish opt-out clause as grounds for an equally categorical dismissal of every potential Danish involvement in a redistribution or resettlement.

From the 1980’s ‘neighbouring states strategy’ to Tony Blairs ‘new vision for refugees’

In Danish debate, many have criticised the cynicism and irresolution of the EU leaders. One of these voices was Asger Aamund, who in an editorial, ‘Sea of Horrors’ wrote, ‘In the EU, we don’t want to appear as brutal racists, who won’t help black Africans find a new existence in Europe. But neither do we want them to be here. So we take the easy option. And that, as we all know, lies at the bottom of the Mediterranean’. The argument that politicians are cynical and irresolute is difficult to challenge, but the devil lies in the detail, and Aamund’s main aim is to launch the idea of establishing so-called ‘refugee communities’ in neighbouring countries, where the refugees can go, from where they can seek asylum and, from where European industry can choose the cheap labour that it requires. A neo-colonial ‘work and protection’ zone, if you will.

This proposal is nothing new. Aamund’s own party, Liberal Alliance (LA), together with Dansk Folkeparti (DF) have previously suggested it, but the idea actually stems all the way back to the time of Anders Fogh and Tony Blair, and even further back to the Schlüter government.

The idea of moving the handling of asylum cases to refugee camps outside of European territory was first formulated in 1986 by the Schlüter government in the UN’s Third Committee. Here, Denmark launched what was called a new strategy for a ‘world community with refugees’. This should include greater support to the neighbouring areas together with UN controlled ‘refugee centres’, from where people could apply for asylum in Europe. These centres were intended to relieve the application process in the individual countries. The suggestion was formulated as humanitarian, but in reality, was aimed towards changing the whole system of protection for refugees by removing the link between the territory of a country and their duty to offer protection. The proposal was rejected by the UN and roundly criticised by several countries. However, the idea continued to exist within the European political imagination and resurfaced again in 1993, when the Dutch Minister for Justice, Aad Kosto, re-launched it at a meeting with his colleagues.

Fast forward to 2001, where the new Danish VK government, lead by Anders Fogh and with the parliamentary support of DF, attempted to revitalise the idea once again. ‘Reception in neighbouring countries’ became a buzzword repeated at many press conferences, and throughout Denmark’s presidency of the EU, they worked closely with the UK and Holland to make the proposal official EU policy.

Camps in neighbouring countries as a tool for deportation

The idea of camps in neighbouring countries demands co-operation with a third party, but Fogh’s government were already quick on the defensive: in some conclusions from a 2002 meeting in the Justice and Home Affairs Council, it is stated that a close co-operation with Gaddafi’s Libya in order to prevent ‘illegal migration’ was not just ‘desirable, but essential’ – despite the fact that Libya failed to acknowledge the Refugee Convention.

The year after, in 2003, the idea gained even more momentum as Fogh’s ally, Tony Blair, presented a comprehensive version of the proposal under the name ‘A New Vision for Refugees’. Exactly as with the Danish and Dutch proposals, the British government repeated the assertion that the existing asylum system was flawed, and that the only solution was to export the handling of asylum processing to Eastern Europe and North Africa.

Although the basic idea in the Danish, Dutch and British proposals was the same, the British version was to a greater extent formulated as security policy, and far less as humanitarian innovation. Among other things, the British government argued that the existence of external camps would make it possible for the European countries to deport asylum seekers en masse to the camps, and thereby away from European territory. Other ideas included plans to attack countries in order to prevent mass movement of refugees, which also tallied with the fact that Great Britain, Holland and Denmark were at the same time involved in planning an invasion of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. The British writers were very clear about the fact that these plans would be in breach of both the Refugee Convention and the Convention on Human Rights:

However, the ‘New Vision for Refugees’ met a sorry end at the EU’s Minister meeting in Thessaloniki in 2003 and also invoked strong criticism from the UNHCR, Amnesty International, the European Parliament, as well as from Sweden and France.

The development of the ‘neighbouring states’ proposal in EU politics: RPPs and Schilys ‘The Libyan Option’

However, the proposal had yet another chapter, when the Justice and Home Affairs Council asked the Commission to continue working on the idea. In June 2004, the Commission also presented the idea of Regional Protection Programmes (RPPs), which should ensure safe access to asylum for refugees, distribution after their arrival by voluntary agreement, resettlement of vulnerable people from neighbouring countries and recruitment for work. The RPP idea was, however, met with strong resistance, and even though small pilot projects were supported in the Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova and Tanzania, their development was hampered by the EU states’ reluctance in terms of accepting re-distributed refugees. The plan to develop external access to asylum was therefore quickly put to bed. The somewhat diplomatic explanation provided by the Commission stated that the EU member states didn’t have ‘sufficient common perspective and belief’ in order to realise this policy. The following years would see the idea of externalised access to asylum being in reality integrated into a deportation and control system, which offered refugees anything other than protection and access to asylum.

At the end of 2004, the Commission arranged a Technical Mission to Gaddafi’s Libya, to investigate the country’s suitability as a close EU partner, something both the Danish and British governments had argued in favour of. While there, the Commission found that a developed co-operation between Italy and Libya already existed, consisting of 47 Italian deportation planes, and the Italian sale of GPS equipment, 6,000 mattresses and 1,000 body bags to the Libyan border guards.

The Technical Mission established a report, which turned a blind eye to Libyan systematic abuse of human rights and the fact that Libya was not a party to the Refugee Convention. The report avoided specifically assessing Libya’s suitability as an RPP. Instead, it recommended that the union send more money and equipment to Libya, and also advised the country to increase the number of border guards from 3,500 to 42,000. The Council for Justice and Home Affairs wrote in 2005 that, ‘any cooperation with Libya can only be limited in scope and take place on a technical ad hoc basis’. Although that formulation might sound hesitant, in reality it covered up the expansion of the EU’s co-operation with Gaddafi in terms of intercepting refugees. Between 2004 and 2006 alone, via the financial Aeneas program, the EU supported ten pilot projects in Libya.

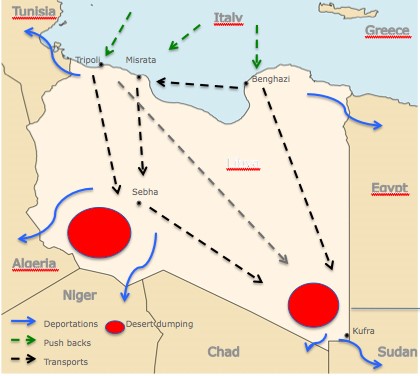

One of these, called ‘Across Sahara I’ involved the Italian Ministry of the Interior and the Libyan army and was intended to ‘combat’ illegal immigration from Libya to Italy. The EU commission paid €2.6 million of the project’s combined €3.2 million. Later on, from 2009, Italy and Libya also co-operated on a ‘push back’ of boat refugees in the Mediterranean. This involved Italian ships intercepting boats, refusing to receive the people on board as asylum seekers and instead, delivering them to Libyan military units, which imprisoned the refugees in Libyan camps.

In 2005, Otto Schily and his Italian counterpart, Guiseppe Pisano, developed the now altered idea of externalised refugee camps further, with a focus on mass deportations – both of all spontaneous asylum seekers on European soil as well as the boat refugees rounded up in international waters. They repeated the dismissal of the proposal to process asylum applications in camps outside of Europe, but were able to accept that the camps would asses and rank people, and issue temporary working visas to the migrants that European industry had the need for. As Schily and Pasano said, both Germany and Italy had good colonial experiences with African work regimes. The idea of secure European asylum processing for refugees outside of European territory was transformed beyond all recognition. The focus was now on deportations away from the EU and on intercepting refugees before they made it as far as EU territory. The official European rhetoric about the need for secure access to the European asylum systems for refugees disappeared right around the time that the informal, ad hoc and EU-supported co-operation with Gaddafi’s Libya began to gain traction.

Brutal Libyan conditions for refugees, in the past and present

Today, EU ministers use the existence of cynical and brutal smugglers as the reason for a military intervention in Libya. But are brutal conditions really something new? In the 2000s, beatings and abuse of refugees was commonplace in the Libyan camps but back then, the EU leaders didn’t even raise an eyebrow over it. In 2009, Human Rights Watch described the conditions in the Libyan camp regime as ranging from ‘inadequate to brutal’. The same year, a female refugee told the following story about her time in a Libyan camp to the Jesuit Refugee Service:

Year after year, organisations such as Human Rights Watch, Médecins Sans Frontières and Amnesty International have documented masses of similar cases in Libya. The co-operation with Gaddafi continued undaunted, and was even defended by the EU. The then vice director for Frontex, Gil Arias-Fernandezm commented as follows on the Italian-Libyan push-back practice:

That paradoxical humanitarian argument for co-operation with the brutal Libyan regime has a present-day parallel: the EU argues that military intervention against the people smugglers that operate out of Libya would stop the dangerous boat voyages. It is doubtful that the route can be closed, but even if it could, this argument choses to ignore the conditions refugees who have no possibility for escape would then be exposed to in Libya.

Watch 27 min video about the rescue action off the coast of Libya and Libyan detention facilities.

EU and Gaddafi

The EU ministers indignation over the smugglers treatment of refugees therefore rings a little hollow, when you remember the many years of tacit co-operation they have had with Libya as the EU’s unofficial outpost. As late as 2010, shortly before the so-called Arab Spring, advanced plans existed for an RPP project in North Africa, at a cost of €3.4 million. At the same time, in autumn 2010, the Commissioner for Justice and Home Affairs, Cecilie Malmström, also travelled to Tripoli and promised to pay the Gaddafi regime €60 million, if it continued with the control and camp system. This wasn’t exactly the best PR for EU asylum politics, and after Gaddafi’s fall, efforts have been made – without success – to establish an EU Border Assistance Mission to fill the void. The EUBAM ended with the majority of the EU officers returning home again and this fiasco underlines the massive problem with the concept of ‘refugee societies’, namely, the assumption that you can ‘just solve’ Libya.

A terrible answer would be to send European military forces into Libya – this would be nothing more than new colonialism of the one-time Italian colony, this time motivated by a regard for asylum policy. Nothing suggests that these countries, or indeed, the permanent members of the UN Security Council would accept this. Even if they did, in all likelihood such a ‘boots on the ground’ approach would not deter unrest. Rather, it would result in a common enemy, which the competing Libyan governments, militias and IS-factions could unite to fight against.

The concept of applying for asylum from neighbouring states is not something that’s just appeared out of the ether. It has a history, and a particularly bloody one that that, characterised by political lip service, resulting in the camp system that intercepted refugees and hindered them in seeking asylum in European territory. Instead, they were circulated as profit between the military, police and smuggler networks and subject to constant attacks. Despite the fact that the suggestion of ‘refugee communities’ is formulated in humanitarian language, we risk, consciously or otherwise, reactivating the political desire to deport all asylum seekers from EU soil. We also run a much more fundamental risk – that it would result in exporting Europe’s responsibility for the protection of refugees away from our territory. Based on the current political climate in Europe, it seems doubtful that the connection between territories and humanitarian responsibility could ever be re-established, should it first be allowed to break.

Sources:

Martin Lemberg-Pedersen, 2015, ’Losing the Right to Have Rights.’ I Andersen, E.A. and Lassen E.A. (eds) Europe and the Americas: Transatlantic Approaches to Human Rights. Brill.