Denmark tears Eritrean families apart

Immigration Service misinterprets the registration of marriages in Eritrea, and thus separates hundreds of spouses from each other and many children from their parents

FACTS:

Since 2014, 4,300 refugees from Eritrea have gotten asylum in Denmark. Out of these, around 2,700 have applied to have their children and partner brought to Denmark. Many have waited for over two years for a reply to their applications and as of March 2017, the average waiting time for Eritreans was up to 437 days (link in Danish).

After the long waiting time, 52% of applications on behalf of partners end up being rejected – a figure only surpassed by rejected Somali cases. In all, over 400 spouses have had their applications rejected during the last 17 months.

In 2016, 65% of permits given to Eritreans went to children, but some of these children have been granted permission simultaneously with a rejection to their other parent.

Denmark does not have many years of experience with Eritrean cases. There has been a sharp and sudden increase in their number from 10 in 2013 to 1,511 applications in 2015.

Source of numbers: statistikoversigt page 12-13 and årsstatistik page 27-28 (in Danish only).

What do the authorities investigate?

As a refugee, you are entitled to bring your immediate family (spouse and children) and therefore don’t have to live up to all the other criteria that normally apply for family reunification. However, you must be able to document (as far as possible) that you really are family. Applicants must fill out a long and detailed form and submit a range of documents. The Immigration Service compares with the refugees’ asylum interviews, which contain answers to questions about family relationships and cohabitation. Afterwards, the family member in question can be called for an interview at a Danish embassy and can also be asked to provide DNA-tests for children included in the application, if the documentation is deemed wanting.

Apart from missing documents, rejections can be given if the spouse is an Ethiopian citizen, if the couple has given conflicting information, or if the refugee said that he/she was unmarried during the asylum application.

There is a risk of cheating if the papers aren’t entirely reliable. For example, you could bring your sister here if you pretended that she was your wife – or your sister’s children, if you said they were your own. People can also marry a distant acquaintance shortly before leaving, and perhaps also receive payment to do so.

However, when 52% are rejected, it must also impact on a number of genuine and honest families.

Marriage certificate not recognised

Even the 48% that do get permission is not granted that on the basis of the marriage, but on that of co-habitation – even though they are actually married. The marriage certificates they supply are simply not recognised.

It would appear that the Danish authorities have misunderstood the validity of Eritrean marriages. In Eritrea, there are three forms for matrimony – religious, traditional and civil – all of which are fully lawful. Both partners must be over 18 years of age and present at the ceremony. According to law, all marriages must be registered afterwards at the local national registration office. And this is where the Danish authorities’ misunderstanding comes into the picture, as they demand that couples must have evidence for this civil registration.

Almost all Eritreans in Denmark have been married in an Orthodox Christian church in Eritrea, and almost all can provide the genuine certificate from the church. However, very few have ever gotten a certificate from the civil register as there is seldom any reason to acquire such a certificate in Eritrea and it is also only possible to do so in the larger cities.

Marriage certificate from church (extract)

Civil registration of marriage (extract)

Information detailing that all marriages must be registered at the civil office comes from Eritrea’s own ambassadors and the government’s website. In many ways, this closed dictatorship wishes to give the impression of being an effective and modern administration, something which is greatly at odds with reality. Rather, the country’s administration and government are generally slipshod, full of corruption and very underdeveloped. Even in the capital, there are electrical outages several hours a day. According to several experts and concurrent statements from the many Eritrean refugees, civil registration of marriages occurs seldom and if it does, you get no physical proof of it. And, most importantly, registration is not necessary to make the marriage lawful.

Although the law states that you must be 18 to marry, it still happens – especially in the countryside – that girls are married before they turn 18. Young girls can be called for military service from around 16 years of age but they can avoid it if they get married and become pregnant.

Dates form another element of risk in the family cases. In Eritrea, two calenders are used: the Gregorian (the one we use) and the Geez calendar, which differ around 8 years. If an Eritrean marriage took place 10.02.2008 according to our calendar, it might say 02.06.2000 on the Eritrean marriage certificate. The applicant is rarely aware of this problem. Birthdays are usually only celebrated for small children, and the date of birth doesn't carry much significance. Therefore many Eritreans do not know exactly when they were born. Even the country's authorities might put a random date of birth on a paper, and there is no central register.

Eritrean culture

Marriage and family are the foundation for the entire culture, and the majority of Eritreans are very religious. People often marry at a young age and it’s not unusual to have many children. Women are as a rule younger than their husbands and people choose their own marriage partners, after an engagement period and with the permission of the families. Weddings are – where the budget allows – large parties with several hundred guests and can even take place in two towns over two days if the couple comes from different places.

The ceremony in the church takes several hours and even poor families scrape together the fee for a video recording and special wedding photos – although cameras and smartphones are rarities outside of the largest cities. Legally, it’s very difficult to be divorced. There must be a special reason and you must also be granted permission from the local council of elders. It occurs rarely. All in all, Eritrea has a very romantic and traditional culture, where marriage plays a big role.

Impossible to get documents after leaving

Given that it’s illegal and punishable to leave Eritrea, no passports are issued – apart from those for official representatives. Neither can you request to get an official document sent after you’ve left, unless you sign a ‘letter of repentance’ and pay 2% of your income to the Eritrean state – a practice the UN has declared illegal and which is paradoxical in that the person has been granted asylum because they require protection from the self-same state.

Nonetheless, the Danish authorities demand that people provide the civil certificate – which almost nobody has. This leads to three scenarios: 1) The majority inform the authorities that they don’t have one and can’t acquire one. 2) Some pay for a fake certificate, often made in Sudan, which is then rejected as such. 3) Some few manage to get family members in Eritrea to acquire the certificate through bribery and the right connections. However, the Danish authorities do not necessarily approve these certificates.

Even asking family members to help acquire a certificate is not without risk, as the Eritrean regime has a tradition of punishing families collectively: if a son has fled, his father may be put in prison. He won’t be brought before a judge and will be imprisoned in inhumane conditions until his family can buy his release.

Cohabitation and interrupted cohabitation

The 48% of spouses who actually do get permits for reunification generally never get it because their certificate was accepted but because they have lived together for a period deemed long enough. The permit states, “We have not recognised your marriage. You have been granted a permit as cohabitors. You are registered as married and must, therefore, present yourself at the Citizen Services Centre in order to have this corrected”. They can then get married again in Denmark.

The magical time limit of establishing a family life the Immigration Service has set is ca. 18 months. If you’ve lived together for less time than that, it is deemed insufficient. And this also applies even if genuine cohabitation has been shortened due to one or both of the partners having been imprisoned or forced into military service. Almost everybody is enrolled in military service, and this can go on for 10 years – sometimes in the other end of the country, and only permitted to leave once a year. This puts some limits on cohabitation. Immigration Service also demands that you had your own place to live – it’s not enough to have lived in a room at either set of parents. In Eritrea, you will normally not live together before getting married.

Finally, cohabitation can also be viewed as ‘interrupted’ and here little regard is taken as to whether this interruption was voluntary or not. Often, it occurs because of forced military service, prison or fleeing from the country. On this point, Refugees Welcome has, however, succeeded in getting the Immigration Service to reopen a number of cases for re-examination. There remains though, a degree of uncertainty in terms of a number of cases where the man fled to Israel several years ago and the wife later ends up in Denmark. Israel is now suspending the two-month residency visas, which many Eritreans have had - and they have never had the chance to get their families there.

Desperate situation for the families

The Danish state is thus separating families that have a right to be reunified according to article 8 of the European Human Rights Convention, as they are lawfully married and not separated by choice. This also gives rise to almost irresolvable situations as nearly all of the spouses awaiting permission – the majority of whom are women – have left Eritrea illegally and are now in Ethiopia, where they live in refugee camps from which they cannot return home. They cannot, and will not, get married again as they are already married.

The majority of spouses and children have been forced to leave Eritrea during the application process, something that is punishable, comes with great risk of imprisonment and invariably involves the payment of large sums of money as bribes. They have been forced to do this in order to be able to furnish the DNA tests for identifying the children, which the Danish authorities almost always demand. They must also leave the country in order to be ready to collect the permit when – or if – it comes at the Danish embassy in Ethiopia or at the Norwegian embassy in Sudan.

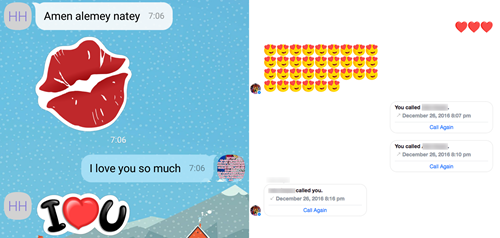

The spouse who then has their application rejected loses the last of their trust in their partner living in Denmark, who has already been pushed to breaking point by the long waiting time and the often minimal economic support he has been able to send to his spouse. Many become angry and accuse their husbands of having found someone else or of abandoning them. A common factor for almost all of them is that they have suffered greatly during their separation and cannot imagine a life without each other. This is borne out by the correspondence between couples, which Refugees Welcome has seen during appeals.

Viber and Messenger messages from rejected couple

Children are separated from one parent

If the DNA test proves that the refugee resident in Denmark is indeed father or mother to the relevant children, they almost always get permission to bring the children here. However, the other parent does not necessarily get permission. In letters of rejection, the Immigration Service write directly that it is up to the parents to choose whether the children should live in Denmark or remain with the other parent – which often means living in a refugee camp in Ethiopia. In this way, children are cut off from living with both of their parents, which is in violation of articles 9 and 22 of the Children’s Convention. The child cannot even hope to maintain regular contact with both parents as both Denmark and Ethiopia have strict visa rules and both parents are refugees.

Mothers often don’t believe that the state can seriously come with such as Solomonic solution and therefore accuse the fathers of attempting to steal the children and abandon them.

In January, the news paper Information wrote about a father from Sudan (in Danish), whose three small children got permission while their mother got rejected. It was one of Refugees Welcome's cases, and it was reversed shortly after. But many Eritreans are still in similar situations.

EXAMPLE:

Filmon was granted asylum in Denmark in 2014. He has been engaged to Senait since 2009 but could not get leave from military service to marry her and was forced to live in a military camp. He visited her as often as he could; luckily, he was stationed close to her and they saw each other often. They had a daughter together and shortly afterwards he was forced to flee the country. He applied for family reunification and waited a year and a half for the answer. Meanwhile, Senait had fled to Ethiopia with her daughter and DNA tests proved that Filmon was the father. The daughter was granted permission but her mother was rejected. The reason: the mother and father had not established a family life. The girl is now 4 and lives with her mother in a refugee camp. Her mother is in despair, as she won’t send the little girl to Denmark on her own but if they return to Eritrea, she’ll have to serve a long prison sentence for illegally leaving the country.

Memo on the problem

Refugees Welcome sent a letter outlining the problems concerning Eritrean family reunification to the Danish foreign authorities in January 2017 and after six months we received an answer from the Immigration Service (the Ministry and the Immigration Appeals Board have not replied). The Service cites a list of sources that actually support our assertion that there is a lack of precise information concerning the registration of marriages in Eritrea. Despite this, they continue to insist that a civil certificate must be submitted. They had no response to the question of children being separated from the one parent.

Refugees Welcome have run a series of appeals for Eritreans, some of which have led to reversals of decisions by the Immigration Service, others of which have not yet been processed by the complaints board of the Immigration Appeals Board.

Dutch experts in agreement with Refugees Welcome

In Holland, the practice is the same as here in Denmark and a court in Amsterdam has recently ruled that a religious marriage from Eritrea is not necessarily invalid just because it’s not registered at the civil register. In May, an expert hearing, together with a report from Amsterdam University’s Faculty of Law, stated that religious marriages are lawful in Eritrea, that spouses are rarely in possession of a civil registration and that they cannot be expected to acquire one after they have left the country illegally.

More info on Eritrea: Martin Plaut: "Understanding Eritrea" (Hurst, London, 2016)