Can you survive on integration benefit?

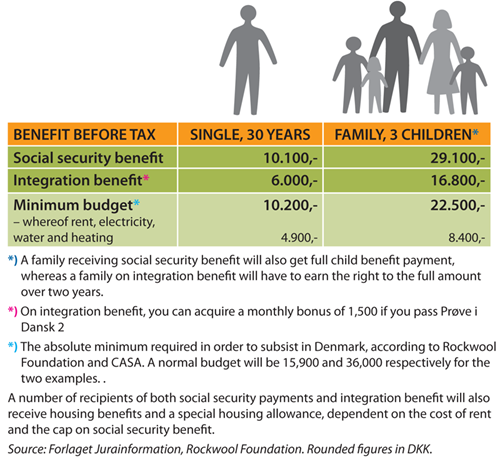

Many refugees are living on an income that is just half of what researchers estimate to be the minimum required to exist in Denmark. See budgets here.

The introduction of a cap on social security benefits was given great attention by the Danish media, but there were few stories concerning the 26,500 who were hit by the introduction of integration benefit on July 1st – apart from those focused on the fact that a number of Danes would also be affected by the reduced benefit.

Recently, Rockwool Foundation and CASA have carried out an investigation (in Danish) into how much it costs to live at an absolute minimum level in Denmark. The amounts are roughly equivalent to the current social security benefits after they were capped, whereas integration benefit equates to ca. half the amount.

Disposable income

Recipients of integration benefit have a far lower disposable income than those receiving social security benefits, as outgoings for rent are the same regardless of which payment type you receive. Many claim that real poverty doesn’t exist in Denmark but the figures below show that 26,500 new Danes quite simply don’t have enough money to put food on the table.

As the table demonstrates, those on social security have just enough to survive in Denmark, if they keep their costs to a minimum. For example, the budget for a single adult earmarks 1,900 DKK for food and drink. But this is impossible for those on integration benefit. After tax, a single adult receives 5,100 DKK and even the cheapest accommodation, incl. water, heating, electricity and licence will cost ca. 3,800 DKK. This leaves a disposable income of 1,300 DKK for food, clothes, transport, medicine, telephone and so on. Insurance, sport and new purchases are absolutely out of the question. Make your own calculation here (in Danish).

Many single refugees have less than 1,500 DKK each month, even with housing subsidies. Local municipalities are obliged to find a permanent residence – but only once – and there is a shortage of cheap, small apartments in most districts. Municipalities have also been granted permission to lodge two people per room, and this ‘temporary’ accommodation can easily stretch for more than a year.

A refugee has no option to move to an area with cheaper apartments as they are tied to the local municipality district chosen by the Immigration Service for the duration of their 3-year integration period. It’s not always possible to move within a municipality either, as the administration won’t approve private landlords or loan money out to cover a new deposit.

EXAMPLE:

Berhe in Ikast has just gotten a job, but before that, his finances looked like this:

Integration benefit after tax: 5,084 DKK

Special subsidy §34: 804 DKK

Income in all: 5,888 DKK

Rent (61m2, 1 room) w/heating and antenna fee but without internet and licence: 4,087 DKK

Electricity: 550 DKK

Basic fixed outgoings in all: 4,637 DKK

DISPOSABLE INCOME: 1,251 DKK

The municipality refunds the cost of transport to and from language school.

Family reunification

A specific problem arises for the many refugees who have come here alone, but have applied to have their partners and children brought here through family reunification. If they move into a small apartment, the municipality will just have to find a larger one before too long, and they can’t always guarantee this. Therefore, many end up living in larger apartments that cost far too much for one person and the housing subsidy doesn’t reflect this. Waiting times for family reunification have been increased and many have waited for more than a year.

Mouhamad from Syria lives in Kolding municipality, which he came to in February 2015. Just three weeks later, he submitted his application to have his wife and four small children brought to Denmark from Turkey, where they had been living in squalid conditions and without an income. The Immigration Service told him this process would take 3-4 months. He therefore asked the municipality to find a larger apartment. However, it ended up taking 15 months to get their permission and for eight months, Mouhamad paid rent that was higher than his integration benefit. Read an article about his case in Information (Danish only)..

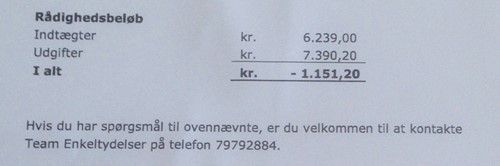

A Danish friend helped him to apply for special subsidies from the municipality. In October, the municipality told him that he’d have to move to a smaller apartment, but that same month, his application for family reunification was approved. He received just two months support in order to survive with the argument that ‘you’ve managed to support yourself from February until October’. In the same letter, the municipality calculated that Mouhamad’s disposable income during the months in question had been -1,151.20 DKK. By some miracle, he had survived with help from friends, the local Arabic organisation and the local branch of the Red Cross. For the first 7 months, he was in full-time work experience at Bilka, but in the end he was forced to stop as his mental health had been so negatively effected by the family’s situation.

When Mouhamad’s wife and four small children arrived in November, all of the children got a fever and a rash. When the doctor finally had an appointment for them three weeks later, it turned out to be scabies. Medicine and ointment cost 1,600 DKK but his wife and their children had not yet received any money from the municipality as they were waiting on the NemID and bank account. They applied to the municipality for emergency help for medicine and were informed that there is a 4-week handling time for applications and that there would also be closure for the Christmas holiday.

In two similar examples with men waiting alone for their families in large apartments, they had just 875 and 494 DKK left when the main outgoings had been covered. Both have been in this economic situation for ca. 1 year.

When their families eventually get permission to come here, the next problem arises: how can they raise the money required for flight tickets and embassy fees? The latter costs 1,500 DKK per person and tickets for a wife and three children from Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan or Lebanon can easily cost up to 15,000 DKK, those from Turkey, a little less. The Danish state no longer helps to cover these costs and it’s impossible to loan from banks or the municipality. Minister for Integration, Inger Støjberg, has stated (in Danish) that people must save up to cover the costs. However, the reality of the situation is that it couldn’t happen without the myriad of private donations from neighbours and friends. Refugees Welcome takes applications for a subsidy towards the costs, which so far has been funded by private donations. Family members abroad generally have no income and survive on a shoestring in refugee camps or with relations.

Establishing a life in a new country

As a newly arrived refugee, you have the right to a start-up subsidy from the municipality, to cover things such as a minimum of furniture and equipment for your new home. It goes without saying that when you come directly from an asylum centre, you need everything from towels to cutlery and a fridge. Municipalities have very different interpretations of what this amount should be and how it should be administered – there are no national guidelines. One municipality might transfer 20,000 DKK to a bank account and also offer to cover transport of the new purchases, while others buy some basic things in Ikea on behalf of the refugee in question.

Often it’s just the first one to arrive who gets start-up subsidies. If more family members arrive at a later date, they won’t be given any support to cover the cost of more beds, wardrobes etc. As a newly arrived refugee, it’s impossible to borrow money or buy things on credit so long as you can’t present pay slips for the last three months.

Asif, a young man from Afghanistan, moved into Holbæk municipality the year before last and spent the first winter months living in a cabin at an empty camping site. When he finally got a room in a shared apartment, the municipality told him that he’d already received the start-up support of 4,000 DKK when he first arrived. He had used these on food and train tickets to cover the gap that occurred in between payments from the asylum system and the first benefits from the municipality. Had it not been for a good Danish friend, who brought an extra mattress in her car, he’d have been sleeping on the floor for the first months.

Refugee children are especially poor

Children make up ca. 40% of newly arrived refugees, and two out of three of those who are arrive later via family reunification are children. It must therefore be concluded that there are many children on integration benefit. Adults with dependents get a higher payment than single adults, but this difference doesn’t begin to cover the extra costs entailed in supporting children, according to the calculations made by Rockwool Foundation – here, it’s families with children who have the most difficulties making ends meet. Newly arrived refugees also don’t receive the full child benefit payment but must wait for the full amount to be paid gradually over two years. The government has suggested extending the period of accumulation to five years. The whole point with child benefit payment is that it’s supposed to cover some of the costs involved in having children – so this represents direct discrimination against refugee families.

How do people get by?

Luckily, newly arrived refugees are often in contact with some fellow countrymen, often relatives, who have been here for a longer period and who can help in various ways. Some of the ethnic and religious associations here have funds to offer financial support, with the expectation that the recipients will contribute themselves when they are able. Many local Danes also offer great support for their new neighbours, both financially and practically, for example by collecting furniture and clothes in second-hand shops.

However, daily housekeeping expenses and the continual cost of transport and telephone are a big worry for the majority. Many eat just two meals a day and cannot allow themselves a healthy and varied diet. Insurance is completely out of the question, so a break-in or accident can have catastrophic consequences. It’s difficult to participate actively in society when you live in such poverty and this in turn hinders integration. It’s also clear that increasing numbers will be forced to turn to crime and black labour in order to survive.

At the moment, many of the new refugees are engaged in full-time work experience, but this doesn’t afford them a single krone extra. Quite the opposite in fact, as some have experienced that the municipality don’t always cover the transport costs immediately and working physically all day also generates greater hunger. The effect of unpaid work-experience is limited: you have to be in a job with wage-subsidies in order to increase your chance of getting a regular job.

Why was integration benefit introduced?

Integration benefit is a new version of the ‘start help’ that was introduced by the VKO coalition government in 2002. Back then, the reason for its introduction was solely to force people to get a job, but now there is also an extra reason, namely, that Denmark shouldn’t been seen as an attractive country for asylum seekers. While in practice, ‘start help’ had the honour of getting 14% into employment after 5 years, in contrast to the 9% of social security recipients, but was also met with sharp criticism as it also gave rise to unnecessary poverty (link to article in Danish) and was counter-productive in terms of integration. It was scrapped again by the SRSF coalition government in 2011.

The economic argument isn’t particularly relevant during the first years, as it typically takes 1-2 years to complete Danish language education and there are very few jobs that you can get if you can’t speak Danish at all. Getting a job in Denmark is also greatly influenced by the network and experience you have. The Swedish model appears more logical, where you get normal benefits during the integration period, which covers the first two years and it is then reduced to 2/3. The Danish municipalities have become much more focused on integration, language schools and job training, so the numbers of new refugees in employment will most likely increase, regardless of the decrease in the level of benefit payments.

According to the government’s calculations, 21,000 would be affected by integration benefit, when it was fully introduced on 1st July 2016. However, Danmarks Statistik claims it affected 26,500 and that number remained relatively unchanged up to October. The government’s prognosis stated that ca. half of those affected would be children. The actual number of children cannot be seen in the tables, but 19,200 were involved in the integrations programme, which means they have arrived within the last three years.

The state reimburses 50% of the operative costs and integration benefits given to refugees within local councils and the rest is covered by the budget guarantee (settlement of the block grant). This also applies to the special expenses incurred for deposits and renovation of accommodation. On top of this, the municipality also gets a special bonus of 48,000 for each refugee they get into active employment and 36,000 when the Danish exam is passed within 5 years (see a memo from Allerød council – Danish only). It is curious then, that most municipalities are so prone to penny-pinching and that they reject appeals for help from their new residents, even when they come and tell them that they can’t afford to eat. Grants given under §34 vary greatly. In the three examples of a father waiting on his family, which we named at the start of the article, they received 322 DKK (which was increased to 3,300 DKK after two months), 1,157 DKK and 1,236 DKK, respectively. Berhe, who is single, received 408 DKK.