Women in an asylum system for men

Neither asylum legislation, procedures or accommodation facilities are designed for women, despite the fact that they make up 30% of all asylum seekers

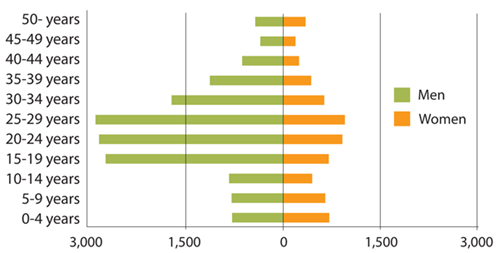

ASYLUM SEEKERS IN DENMARK, GROUPED BY GENDER, 2015

Women and the conventions

The UN’s Refugee Convention was written in 1951 when the world looked very different. It was a reaction to the Second World War and the situations of persecution created by both the war and Nazism. Persecution on the basis of gender and sexual orientation are not named under the definition of a refugee, even though Denmark and other countries now take these aspects into consideration to a limited extent when assessing asylum applications.

The classic refugee is a man. It is typically men, who are involved in politics, are imprisoned, tortured and come into conflict with other groups within society. It is men who join up or are forced into military and rebellious movements. It is also men who are the most active in religious contexts, write critical articles or end up having problems because of their job or position within society. All of this means that men, more often than not, can fulfil the criteria for persecution of an individual and concrete threats.

Of course, there are also women around the world who are politically active and critical journalists, but they are only a fraction of their male counterparts. When women flee, it is often because of situations in which they have had a much more passive role, or where they are in fact fleeing because they are women. The general conditions in a country, as well as ethnic and religious backgrounds, play a greater role for female refugees. Many women flee because of their husband’s problems and are as such dependent upon his application and explanation – or, they are fleeing from their own families.

The UN ratified the Convention on Women’s Rights in 1979 (CEDAW Convention). However, as with the Convention on Children, it requires that the individual state is duty-bound to uphold the rights of its own citizens – when a state obviously doesn’t do this, it can lead to persecution and the Convention on Refugees comes into play. But where exactly do the conventions intersect? In reality, you could argue that the majority of women in, for example, Lebanon, Iran and Afghanistan are entitled to asylum because they cannot obtain protection from the authorities, solely due to the fact that they are women. Recently, the CEDAW Convention has been successfully applied in a handful of cases in Denmark and a small group of lawyers are working actively with it (see more on asyltilkvinder.dk).

Asylum motive: I am female

Some women’s motivations for asylum are gender related, such as forced marriage, bride-kidnapping, circumcision, violence in the home, rape, honour killings, forced prostitution/trafficking, homosexuality or expulsion from the local community/family due to ‘disobedience’ or violation of religious rules. They, therefore, belong to both a persecuted social group and are also vulnerable to concrete abuse and threats from family members or the authorities. It is a type of abuse that provokes guilt and shame, and which you don’t wish to relate to a stranger (especially a male). Carrying out abuse that generates shame and self-recrimination is an age-old and effective mechanism of oppression.

In a number of countries, the law directly allows husbands or brothers to kill an adulterous woman. A man’s suspicion and words weigh far more heavily than a woman’s – no proof is needed at all. Women are the property of men and have no rights. In Afghanistan, a father can sell his teenage daughter to a man 40 years older and she can do nothing to resist it – an influential man can also force parents to give their daughters away in marriage. In Pakistan, many women are murdered in their own homes, without the men ever coming to trial.

The Danish asylum authorities regard these sorts of cases as ‘civil law conflicts’ and women are often directed to seek the protection of the authorities in their homelands. This is, however, not possible in countries where the law, police and religious leaders grossly discriminate against women and define them as disobedient on the basis of claims by male family members. In addition, in many countries, it is a practical impossibility for a woman to live alone and support herself without running a great risk of attack and exclusion. She is therefore entirely dependent upon her persecutors.

Rape is not viewed as torture in an asylum case, not even when it occurs in a prison or systematically in connection with warfare. The risk for female circumcision (FGM) has, in only a limited number of instances, lead to asylum in Denmark, also when dealing with cases from Somalia, where 98% of all girls are mutilated.

As a rule, belonging to a persecuted minority is not sufficient grounds in itself, and the general conditions within a country must be extremely dangerous in order to be granted asylum – as can be seen with Syria at the moment.

All it all, it can be concluded that women are in a worse position when it comes to the specific motivations for asylum.

Weaker protection

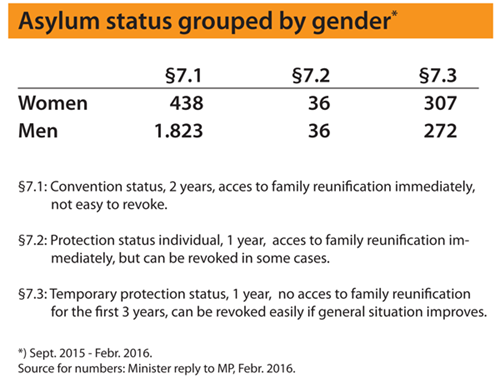

In the case of Syrians, the majority of men are granted convention status (due to forced military service), which is the strongest form of protection, while nearly all women are granted far weaker protection under §7.3 (due to the general conditions in the country), which only grants asylum for 1 year without the right to family reunification for the first 3 years, and which can easily be revoked again. The table shows all asylum approvals – not just Syrians. It appears that 4 men for every woman are granted the strongest protection (§7.1) and that more women than men are granted the weakest (§7.3).

Family-related conflicts will often lead to asylum under §7.2, which is also more uncertain than convention status and which, just like §7.3, can also be revoked.

Single women from Afghanistan are a particularly vulnerable group. As a woman, it’s impossible to survive if you don’t have a family to support you. This fact can give rise to residency visas in seldom cases, but according to the Aliens Act, it falls under humanitarian residency (§9b), which is a weak and short-term type of protection, even though it should fall under §7.2 as it has more to do with protection against inhumane treatment than humanitarian considerations.

Finally, it is a typical pattern that men flee in advance and leave their wife and children either in their home country or in another country along the way. This is often perceived as men abandoning their families, but in reality, it is a decision that the family are forced to take. Firstly, it is often the man who is in the greatest personal danger and secondly, ‘Fortress Europe’ forces refugees to take an expensive and dangerous journey, which men try to avoid inflicting on their wife and children.

The consequence of this pattern is that the man is granted asylum and afterwards gets his wife to join him through family reunification. The majority of those who come under family reunification are women and children. This also places the woman in a weaker position, as she is now fully dependent on her husband, in order to be able to stay in Denmark. Should they be divorced, she would have to leave the country, unless she can prove the violence and has built her own attachment to Denmark over minimum two years. She has the right to apply for asylum when she arrives. However, the majority are not aware of this and even if they were, they would run a great risk of having their applications rejected, as this article has shown.

Asylum procedure

The way through the asylum process is long and seems mostly concerned with establishing the applicants’ credibility. Here, women are once again in a worse position than men, when it comes to writing their stories down, going through personal interviews as well as seeking information and guidance.

This is because women from the countries in question are more insecure when it comes to sitting opposite a stranger and explaining their backgrounds coherently and chronologically – they have less education than men, seldom speak more than one language, their motives for asylum are often more personal and shameful to relate, and finally, they are often also responsible for children.

In this way, some women will be more uncertain, less well prepared, more emotionally affected by the situation and more alone with their worries and questions. If a woman has a small child, she will, as a rule, have the child with her during the asylum interview. You can’t directly see from the statistics whether or not women are rejected more often than men, as the numbers aren’t tallied on the basis of gender. However, a number of women who travel here with their husbands will be granted asylum on the basis of their husband’s motives.

INFO:

TOP 5 NATIONALITIES THAT SOUGHT ASYLUM IN DENMARK IN 2016: SYRIA, AFGHANISTAN, STATELESS, IRAQ, MORROCCO

The journey and residence in asylum centres

Even before women arrive in Denmark, a large number of them fall victim to attack and rape along the way – both before and after their arrival to Europe. Amnesty has documented this in a report from 2016, and we often hear accounts of it at Refugees Welcome. Men who have travelled across the Sahara, through Libya and over the Mediterranean often say, “It was terrible for us but even worse for the women”. It’s common for newly arrived women to be pregnant after having been raped on the way. After their arrival in Denmark, there is no systematic investigation of whether they have been victims of abuse and whether they require help. They must inform the authorities themselves at the general doctor’s examination and even if they do this, they have very limited access to therapy and psychological support.

Asylum centres are not divided by gender and the majority of residents are single men. You don’t share a room with the opposite sex unless you are a couple, but will often share a kitchen and bathroom. There are very few places reserved for women. Right now, (May 2017), there are 40 asylum centres, of which 8 are centres for children, with ca. 8,000 residents in all. Until now, there has been a half-centre for women with ca. 50 places (Fasan Centre in Kongelunden) as well as a small secure department in the centre at Sandholm, with 8 places for threatened women. Even in 2016, when the number of applicants was over 17,000, divided between 96 centres, no new women’s centres were opened.

The small women’s centre at Kongelunden is due to be closed because of mould in the buildings and the women will be moved to the bigger centre at Dianalund near Sorø. A number of the women whose applications have been rejected in phase 3 has already been moved to the deportation centre at Kærshovedgård outside Ikast, where they make up a very small group among the men.

Many more women would rather live at a women’s centre. They feel very insecure in the large centres, among hundreds of men. Just going to the canteen to eat together with 300 others can be an insurmountable obstacle for a single woman. Rape occurs and is not always reported as it is carried out by men from the same country, who threaten their victims into silence. The centres are often located in isolated areas with long, unlit roads at night and women are afraid to walk home alone.

Integration phase

When women are granted asylum or family reunification, they end up in yet another system, where they are at a disadvantage. They are met with the same demands and the same possibilities as their husbands, as we have equality in Denmark. The problem is just that these women have not grown up in an equal society and have, as named above, had less access to education, less work experience, are used to being relatively dependent on their men and they have a greater responsibility for their children than their partners do. This places them at a disadvantage with nearly all of the parameters used to assess integration in Denmark: language ability, education, work, network and active participation in society.

Access to permanent residency and citizenship is also based on the same factors, and with a temporary residency visa, women are still dependent on their husbands. The cap on unemployment benefits and the 250-hour rule also have the same effect as a number of women fall out of the system entirely and are forced to live on their husband’s income.

Danish society is therefore complicit in reinforcing inequality instead of fighting against it. The numbers also reveal a depressing statistic, where just 5% of refugee women have found jobs after 4 years: that’s just one woman for every four men (numbers from 2015*, the same pattern appears to be presenting itself for 2017*, even though more refugees are entering the labour market). The Minister and municipalities point the finger at refugees’ cultural backgrounds and state that demands must be made and that women ‘should get themselves out on the labour market’.

Interestingly, the statistics in terms of education look completely different. More women than men complete the highest Danish language course (DU3) and when you look at universities, there are many more young women* than young men with non-western backgrounds, completing further education. This might suggest that although female refugees are starting at a disadvantage when compared to men, if they get the chance, they commit and see it through to completion.

However, the Syrian women who arrived during recent years were granted the §7.3 status, which does not give them free access to higher education. And that leaves them with fewer options than the brothers or husbands they came with.

*) links to articles in Danish

Refugees Welcome recommends:

Today, the Danish state continues the oppression and discrimination that many female refugees have been victims of. It must be understood that female refugees often flee for different reasons than men and asylum procedures should be adjusted to reflect that.

There is no economic or rational justification for not creating asylum centers exclusively for women – something that would make refugee women more secure and give them more empowerment.

Women who are granted residency in Denmark need more support and skills development in order to compete with men (and with Danish women). This extra effort can be justified as it can be seen that women are more interested and persistent in terms of education.

Immigration Services and the Danish Refugee Appeals Board:

• More focus on gender-based persecution in assessment of asylum applications (see the UNHCR’s guidelines)

• Inform women that they can request a female interviewer and interpreter, and how they can do this

• More, and smaller, women’s centres

Parliament:

• Easier access to gaining independent residence after family reunification (especially under §9c.1, §26 and §19)

• Ensure better access to interpreters and independent advice at asylum centres

Municipalities:

• Special focus on women in integration endeavours: courses, child-minding, mentors, network