First impressions of Sandholm

Visit Denmark's reception camp for asylum seekers, seen through the eyes of an American lawyer

INFO

In February 2018, I moved to Denmark from the United States, where I had worked as a criminal defense attorney. Although I had some experience representing refugees and asylum seekers in American courts, I knew little about the Danish asylum system. In order to educate myself, I began volunteering at Refugees Welcome, a Copenhagen-based NGO that provides legal counseling services to asylum seekers in Denmark. As an organization, Refugees Welcome has ten years of direct counseling experience based on the idea of treating people who come to Denmark seeking protection and advice with the highest amount of dignity and respect – as fellow human beings.

In May 2018, Refugees Welcome began holding additional counseling sessions at Center Sandholm, the initial processing center for all asylum seekers in Denmark. I accompanied representatives from Refugees Welcome on one of their first visits to Sandholm. What follows are my initial observations- not as an expert, advocate, or judge, but as an attorney, volunteer, and newcomer to Denmark and the Danish asylum system.

Center Sandholm, Denmark’s oldest camp for asylum seekers, sits atop a green hill surrounded by sprawling farmland about 30 km north of Copenhagen. The location is the site of a former military complex and many of its historic yellow buildings still remain in use today. With nothing but fields and pasture on all sides, the camp’s baroque structures and imposing gated entrance stand out.

All new asylum seekers who enter Denmark are sent to Sandholm soon after they arrive. Most remain here during the initial stages of the asylum process, where they are asked to provide background and biometric information before they are picked up in buses and resettled in other camps, mainly in Jutland. Official interviews concerning identity and motives for asylum are also conducted here.

With so much movement in and out of the camp, Sandholm’s population is constantly in flux. When I visited, about 150 men, women and children were present. I was told by a Red Cross volunteer that around 50 more were there earlier in the day, but they had been picked up that morning by the Danish Immigration Service for resettlement elsewhere. At maximum capacity, Sandholm can hold, and has held, over 500 people at once, but today the number of people arriving is much lower.

My first impression of Sandholm was that it looked and felt like the jails I had visited as an attorney in the United States. (In fact, Sandholm was once used as a prison, and there is still a correctional holding facility for asylum seekers attached to the camp.) The grounds are surrounded by a border wall made of solid yellow brick in parts, wired fence in others. Towering lampposts with spotlights can be seen along the perimeter and within the interior of the camp. The main entrance road is blocked by a metal gate supported by large stone columns, with a door on one side through which the camp’s occupants are allowed to leave and visitors can request to enter, provided they check in with the staff of the Danish Red Cross, who operate this and several other refugee camps across Denmark. They sit in a guard house adjacent to the main gate, watching rows of surveillance monitors and documenting all those who enter and exit the camp.

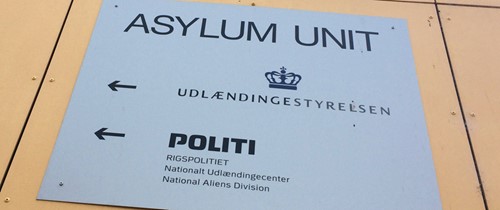

Just beyond the guardhouse stand the on-site headquarters of the Danish Immigration Service and National Police, whose presence in the camp is as ubiquitous as the distinct odor of fertilizer that followed us as we walked, likely wafting from a nearby farm.

After I and two representatives from Refugees Welcome arrived at Sandholm, we were greeted by a Red Cross volunteer who provided us with ID badges and walkie-talkies. He gave us a brief overview of our itinerary – attend dinner with the camp’s occupants, where we would have an opportunity to introduce ourselves and explain the reason for our visit, and then commence counseling sessions in an available activity room. As he spoke, through the window behind him I observed the main gate creak open as a yellow and white police cruiser entered the camp.

We took dinner in the canteen, a long, generic-looking dining hall with white plastic tables and harsh, fluorescent lighting. The walls were empty save for a few scattered flyers and several small watercolor paintings that appeared to have been made by the refugees themselves, perhaps in an art class. One depicted a lush, flat Danish landscape, another a Danish flag in the shape of a heart with the words “thank you Danes” scrawled beneath it in English, and another was a crude drawing, possibly by a child, of multi-colored stick figures holding hands in a circle. We walked over to a centrally located table, spread out the informational pamphlets we had brought, and prepared to talk with anyone who was interested.

Men and women who had been waiting outside began to enter and form a line to receive their dinner, prepared and served by Red Cross staff – a stew made of unclear ingredients served over white rice in a styrofoam container with a side salad and assorted pickled vegetables scooped from a large plastic barrel. Thinly sliced white sandwich bread, emptied from plastic bags, was piled high into a basket at the end of line. One by one, the camp’s inhabitants shuffled past to collect their food. As they did, some began to notice and approach us. We were informed by our Red Cross chaperone, who sat with us during dinner, that he knew of a few others who were interested in speaking with us.

After dinner, he guided us across the camp to the activity room where the counseling sessions were to take place. We passed row after row of small, tightly packed apartments comprising the residential areas of Sandholm. Their resemblance to army barracks betrays their former purpose, and they line narrow streets, some unmarked and unpaved, separated by the occasional patch of green space. The only presence I witnessed on these streets was that of the two police cars that crossed our path along the way.

We passed a group of young children laughing and playing football on a small and steeply graded hill to our right. Behind them, a man smoked and walked in slow, deliberate circles, staring at his feet the whole time. In the distance, beyond the fence, a vast green field approached a dotted treeline. The wind was strong, and I could hear the nearby apartments creak with each gust.

As we made our way to the activity room, I caught sight of the line of people that had already begun to form outside of its door. Our chaperone remarked that they are required to wait outside, and it was a good thing that the weather was nice. He showed us into the room, opened a few windows, and brought us some coffee. He turned to leave, but before he did, he advised that we keep each session to under ten minutes.

We met with several asylum seekers that day in our makeshift office. As I sat and listened to them speak, some in broken English, some in perfect Danish, I detected the common elements of fear, gratitude, and shame weaving throughout their very different stories.

Our visitors included a soft-spoken young man fleeing gang violence in Lebanon, who had been living and working in Aarhus for three years without a valid permit. He was brought to Sandholm after having an argument with his boss over unpaid wages. Instead of paying the young man, his boss reported him to the Immigration Service.

We met with a former Iranian military officer-turned-whistle-blower who fled his country after the army found out that he was leaking confidential information to NGOs in Iran. He, his wife, and his daughter were all terrified because they had heard stories in the camp of government spies sent to track down and kill enemies of the state abroad, even going so far as to pose as refugees themselves in order to get close to their targets. Maybe the threat was exaggerated, but their fear was not.

Next, we spoke with a doctor from Ethiopia and member of a minority political party fleeing state persecution at the hands of his country’s political and ethnic majority. After refusing to cooperate in what he described as the cover-up of state-sanctioned killing, his life was threatened and he was separated from his wife and young daughter. He was ultimately forced to flee the country without them. Because of this, soon after he left Ethiopia, he tried and failed to commit suicide.

At this point in our conversation, the man began to sob inconsolably. As he did, our chaperone entered the room to remind us that our ten-minute time limit was up.

Our final visitors were a middle-aged man from Iraq and his 16-year old son, born and raised in Denmark. They found themselves in Sandholm because two years ago, when the father’s Danish residence visa expired, he moved with his son to Iran for a job opportunity that didn’t work out. When they tried to return to Denmark, the father was denied a visa and told that his only way back into the country was as an asylum seeker. Now father and Danish-born son sit in Sandholm, passing time and waiting to learn if they will stay in Denmark or be forced to leave.

After an hour or so, the Red Cross volunteer entered the room once more and told us that no one else wished to speak. He collected us and guided us back to the main entrance, past the shaky rowhouses and empty streets, where we turned in our badges and radios. We thanked him and said our goodbyes to the rest of the staff. As the sun began to set, we left the camp, making our way through the metal gate and towards the car that would take us back to Copenhagen, back to our homes, the faint smell of manure still clinging to the air.

ENDNOTE

After initial visits in May, Refugees Welcome and the Danish Red Cross came to an agreement whereby Refugees Welcome would be given a key and allowed to conduct counselling sessions independent of oversight or time constraints. This is crucial to fostering an atmosphere of trust, and important because advice must be given on an individual basis – some sessions may take up to an hour or more if the case is complicated. Refugees Welcome continues to visit Sandholm as long as the resources are there, providing weekly visits as a supplement to weekly open counseling at Trampoline House in Nørrebro.

Become a member of Refugees Welcome,

and support our independant counseling