Elderly refugees are vulnerable and more exposed to poverty

Retired refugees are a growing and overlooked group, and they are significantly worse off than ethnic Danish elders

About the study “The new elders”

The study was carried out by Anika Liversage from VIVE and Mikkel Rytter from Aarhus University, and it compares three different groups of elders with minority background to elders with Danish background at the age 65 to 74, based on statistical data from 2018. The first two groups originate from Turkey and from Pakistan – the two countries where the majority of migrant workers came from in the 1970s. The third group arrived later as refugees from the Arabic speaking countries Lebanon, Iraq, Syria and Jordan. The three groups are compared with Danish elders in general, and also with Danish elders who have attended school for seven years or less. The latter group has educational similarities with the ethnic minority elders, who are often very poorly educated. The analysis looks at poverty, employment and accommodation/family relations. Download here (in Danish).

The number of elders with refugee or migrant background is rising all over Europe, and this is a challenge for the health and care sectors. Furthermore, this group is far more exposed to poverty than elders with an ethnic Danish background, and their health is poorer.

The new study shows that ethnic minority elders are significantly worse off than majority Danish elders in several ways – also when compared to majority Danish who only attended primary school. Refugees are more exposed than migrants, and women are more exposed than men. Furthermore, recent legislation will lead to an aggravation of the problem in the future.

Many reasons for the vulnerability of the elders

Poverty especially affects elders with a minority background for two reasons: smaller savings and a limited right to public benefits. Firstly, their connection to the labour market has been shorter, more unstable and on lower salaries, which leads to less savings in the form of pension schemes and investments. For instance, the new study shows that almost all Danish men were working at the age of 55, but only around half of the men in the minority groups.

The majority of these are also renting their home, while most of the elderly Danes own their home, and have therefore gathered assets through that. Furthermore, many do not have the same access to benefits due to a principle of gradually obtaining the right to benefits, in this case you must have lived 40 years in Denmark before you can get a full retirement pension and the special bonus for elders. Refugees were exempt from this demand until 2018, where the exemption was removed.

Denmark has very limited experience with ethnic minority elders, as the first large groups of migrants have only recently retired. The ones who arrived back then are far less integrated than the ones who arrived in recent years; especially many of the women have never been part of the labour market and do not speak Danish. This is due to the fact that as working migrants they did not plan on staying in Denmark and that the Danish state did not really have any integration policy at the time.

This group also often has a smaller network which increases the risk of social isolation. On top of these things, ethnic minorities in general have a poorer health condition than the majority population: more suffer from chronic diseases and obesity, and especially refugees suffer from mental problems caused by trauma.

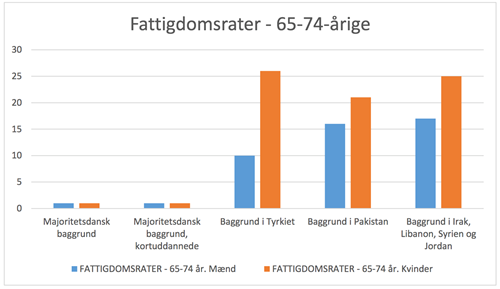

The study also finds large differences between men and women from the minority groups in the analysis: 10% of Turkish men are living below the poverty line, while as many as 26% of the Turkish women do. In comparison, the number for Danish elders is only 1%, and the number is the same for women and men. This mirrors the fact that minority women have a much weaker attachment to the labour market, and many of them came to Denmark several years after their husbands. In this way, minority women are again disproportionally affected, as we have described earlier.

Chart from "De nye gamle": Poverty rates among the five groups (blue/men, orange/women)

An elderly refugee in Denmark is thus in a far less favourable position both economically, socially and health-wise than an elderly Dane. Adding to this difference, the Danish state is less capable of helping elders with a minority background, as the care sector is rarely equipped to include other cultures, religions and languages.

We already have serious problems on this issue within the health sector, as professor Morten Sodemann has often tried to draw the public’s attention to. Language and culture barriers lead to misunderstandings and wrongful treatments.

Furthermore, the situation puts an extra pressure on the younger family members who are forced to house, support and translate for their parents. Many of the elders are not able to pay the required own share for a nursing home placement, so it’s not just for cultural reasons that many ethnic minorities live together across generations.

Photo: Martin Thaulow

Future prospects

While the new Benefits Commission (Ydelseskommissionen) rightly recommends a new distribution of social benefits in favour of providers and thereby children it does not mention the elders.

There is indeed a need to accommodate newly arrived refugee children better, as integration allowance is only about half of the normal social benefits (kontanthjælp), and they are not even fully entitled to the special child allowances. Danish Institute for Human Rights documented in a report from 2018 that many refugee children grow up in serious poverty, which constitutes a breach of the Danish constitution.

However, the elders face similar issues as they have not lived in Denmark for 40 years and thus do not qualify for full retirement pension. There is therefore a need for the Benefits Commission to also include the elders in their recommendations.

An increasing part of staff in the health and care sector with ethnic minority background will hopefully help diminish cultural misunderstandings, but other factors are pulling in the opposite direction: The number of elders is rising, and they live longer. Several of the restrictions that have been introduced in recent years will add to the problems in the future. More elders will have to live on a limited pension (brøkpension), because the principle of gradual obtaining rights now also includes refugees. The demand for self-payment of interpreters after three years in Denmark is affecting many elders. Fewer will be able to obtain permanent residency and citizenship due to an ongoing tightening of the requirements, leading to even fewer being able to buy their own homes.

Nursing homes and hospitals can work on a better cultural understanding, and educational institutions as well as the labour market can become more inclusive. But the structural discrimination which is implied in the law of demanding 40 years in the country before obtaining a pension, the self-payment for translation and the strict access to permanent residency can only be changed through legislation.

As a member you can ensure our future work

for the most vulnerable refugees