Sweden: Refugees with temporary protection have right to reunification

Swedish supreme court says limiting family reunification is a breach of conventions

LINKS:

Download the Swedish ruling (in Swedish)

Read more about the Danish ruling

Download the Danish ruling (in Danish)

Read more about the big turn in Swedish asylum policy in 2016

In July 2016, the Swedish parliament passed a temporary law, which has later been expanded until April 2020. It grants temporary stay for 13 months at a time to refugees who do not achieve asylum as individually persecuted according to the Refugee Convention. At the same time, they have no right to bring their closest family to Sweden, as refugees normally have.

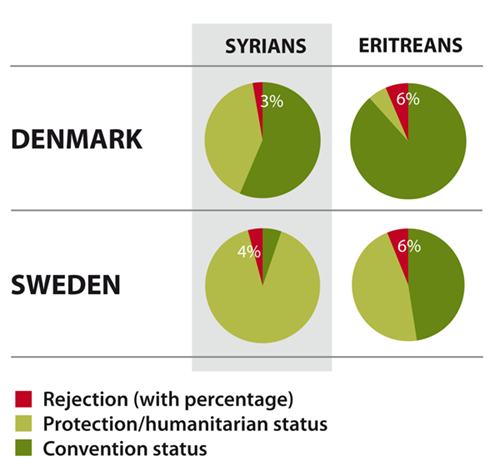

The limitation targets the majority of refugees who are granted asylum in Sweden. On this specific point, Sweden has a very restrictive practice: Only a small part of the Syrians and less than half of the Eritreans are given convention status in Sweden, whereas more than half of the Syrians and almost all Eritreans get it in Denmark. The starting point for the court ruling is exactly the temporary status, and thereby the same person is treated very differently in Sweden or Denmark, already when it comes to the granting of asylum.

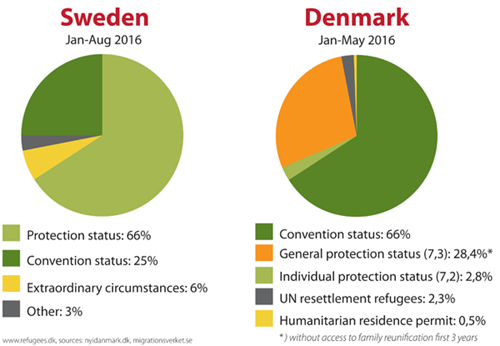

Distribution of asylum status, all, primo 2016

Distribution of asylum status, Syrians and Eritreans, 2016

The temporary Swedish law bears some resemblance to the Danish Article 7(3) status, which is a 1-year permit given to Syrians without an individual asylum motive, and which includes a 3-year quaranteen before accessing family reunification. This law, however, was approved by the Danish supreme court one year ago. The Danish judges found that the state has a legitimate right to limit immigration through upholding a waiting period for family reunification of refugees. Sweden has had a much higher influx of refugees than Denmark, and nevertheless the Swedish judges found that the consideration for the unity of the family and the best interest of the child was more important.

The court ruling will probably mean that Sweden must process a large number of new applications for family reunification – in 2017 alone, more than 14,000 persons were granted protection status.

At the time when the Danish supreme court ruling was made, the number of new asylum applicants was around 300 per month – a very low amount, which has been stable since spring 2016 and still is. There was no challenge to the asylum system – asylum centres were already being closed down by the numbers. It is also remarkable, that the Swedish judges interpret the right to family life much more seriously than the Danish, though they both refer to the same practice from ECHR. An important difference between the two rulings are, however, that the Danish case was about a married couple, whereas the Swedish one was about a child and his parents and brother. The best interest of the child is not part of the Danish ruling.

The Swedish case is about an 8-year old boy from Syria, who came to Sweden with his uncle in December 2015. He was granted temporary protection status in March 2017. His parents and brother had left Syria and had not obtained legal stay in any other country. They applied to be reunited with the son in Sweden in July 2017 but were rejected in two instances (Migrationsverket and Migrationsdomstolen). The authorities recognised that the law is intervening with the right to a family life but found the need for the state to limit the pressure on the Swedish asylum system to be proportional. It was also mentioned that the child was not without caregivers, and that the law was temporary and would not lead to separation for ever. The best interest of the child could not lead to a permit in itself.

Migrationsöverdomstolen, which is the third and final instance, did not agree with this assessment. The ruling refers to practice from ECHR where a 2-year separation between a young child and its parents was found to be ‘very long’ (Nunez vs Norway) and says that when it comes to children, their best interest should come before the wish from the state to limit immigration in a proportion assessment (Mugenzi vs France).

The boy had already been separated from his parents since 2015 and was now 8 years old. The court found this to be a very long time for a child, and that a prolonged separation would be a breach of the Convention on the Rights of the Child articles 3, 9 and 10 as well as ECHR article 8 on the right to family life.