New peace deal between Eritrea and Ethiopia – any change for Eritreans in Denmark?

Limited improvements in sight for Eritrean population

Ethiopias new prime minister Abiy Ahmed visited Eritrea in July, and Eritrea’s dictator through 30 years Isaias Afwerki returned the courtesy. The two countries’ leaders have not visited each other for the last 22 years. The two leaders shook hands on ending the border conflict which rose after Eritrea’s independence in 1991, and has led to a standing army on both sides of the border ever since.

In 1998-2000 the conflict evolved into a bloody war, costing tens of thousands of lives, most of them on the Ethiopian side, and forcing one million to be internally displaced. Large groups of both populations were deported. A terrible situation for two peoples who have much in common and all go under the name of “habesha”. Ethiopia has now decided to accept the border line which UN and Eritrea agreed on back then.

Turning point between the two countries

It’s a historical peace deal, by Western media presented as a turning point in the relationship between the two countries, and many see it as new opportunities for the populations of both countries. The deal is not only about the border line, but also about opening up for trade, direct phone connections and re-opening embassies. News of direct flights between Addis Abeba and Asmara were quickly out. Washington Post wrote on July 13th an overwhelming article about two brothers, separated by the border war in 1998, now reunited at last. Other commentators have been more realistic.

Two questions come to mind when the initial cries of joy have faded out. The first one is, are changes for the Eritrean population really in sight? The next one is, will it have any impact on the 1 million refugees who have been granted asylum in Europe, Canada and USA?

I spoke to people from both countries, living in Denmark, following politics in the region closely. The short answer to both questions unfortunately seems to be No.

First, we have to look at the deal itself. The most striking thing is the inequality between the two leaders and their countries.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia is a powerful player on the African continent with its 100 mio inhabitants and a history as the only country never to be colonized. In spite of many violent conflicts between the ethnic groups of the country and problems with corruption and abuse of power, it is however a fragile democracy with a constitution and rule of law. The economy is growing fast, though the majority is extremely poor.

Eritrea

Eritrea is a small country with 4-5 mio inhabitants (nobody knows for sure), and has been totally isolated from the world since the border war broke out in 1998. The freedom fighter Isaias quickly turned out to be an oppressive dictator, and the country has never implemented its constitution or developed a legal system. Emergency rule has been declared for the last 15 years, and a large part of the working population are stationed on open-end conscription for military or civil service with one month of leave per year. The economy is based on a single gold mine and massive support from the 1 mio Eritreans living abroad, sending money home – both for daily necessities and to pay human smugglers and corrupt government officials large sums.

Transport and trade

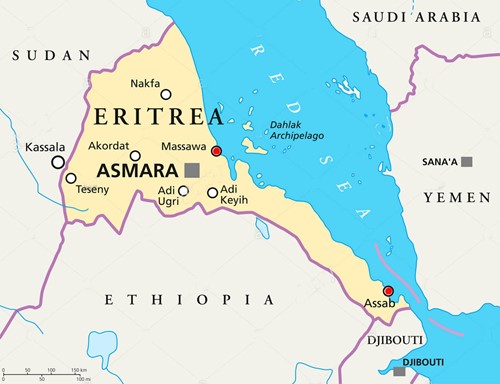

Ethiopia has no access to the sea and transport by ship – which Eritrea has, in the form of the two harbours Assab and Massawa. Therefore Ethiopia is very keen on transporting goods through Eritrea, and is ready to pay fees and duties for it. At the moment, 95% of all goods in and out of Ethiopia is passing through Djiboutis harbours, at a high price. Eritrea needs the money and doesn’t really use its harbours anyway – Assab looks like a ghost town and Massawa is far from the beach vacation place it could be. Transport through Eritrea could mean cheaper goods for both countries and a larger supply.

However, it is doubtful whether Ethiopia or private companies will make large investments in the Eritrean infra structure, as everything depends on Isaias’ personal mood and attitude. It’s risky to invest in a country without rule of law, governed by one man. And nobody knows what will happen the day he is gone.

No political changes

At a glance, it looks like an advantage for Isaias that he can post fewer soldiers at the border with the new peace deal. But in practice he uses both military and civil service as free labour for the state, and also a s a way of oppressing any resistance or individual initiative. Without the threat from Ethiopia which he has been thundering about for 22 years, this will be hard to maintain. If he demobilizes parts of the army, it will lead to unemployment, and a good guess is that he will let small businesses and private income pass under the radar instead of supporting it officially – and keep his power through corruption.

Though an agreement has been reached as to where the border line goes, it does not necessarily mean less border control. It is still illegal for the ordinary Eritrean to leave the country without a visa and a permission – which you will only get if you have the right connections and trust from the government. Eritreans from the intelligence service and the ones who have a Western passport and pay their taxes to Isaias can travel almost freely. It will probably be a little easier for others to get a permit in the future, but it is unlikely that young men can run away from military service and walk across the border. Isaias has promised no changes in the conditions inside Eritrea – as opposed to Abiy, who is constantly talking about development and reforms in Ethiopia. The standard answer from Isaias is “we are looking into those things.”

One of the Eritreans now living in Denmark thinks that the two leaders have probably made a diplomatic deal to diminish political resistance movements in both countries. It is well known that Ethiopian opposition people are working from inside Eritrea and (to a lower extent) the opposite – this can be suppressed by allowing intelligence service from the other country to enter and “talk to them”. Another way is to help some of the most prominent persons to get asylum in Europe or USA, moving them out of the area.

For Eritrean refugees in Denmark, the deal will not have a big impact. It will be easier for them to visit Ethiopia, but if they return to Eritrea they will still face the same risk of imprisonment without a trial, torture and inhuman treatment in the prisons – just for leaving the country illegally, or maybe even having absconded from the open-ended military service. Even children are put in prison for months, if they are caught trying to cross the border.