Refugees forced to live on the street despite legal residence

Fadima got asylum in 2014, but her permit was revoked. While waiting for a decision from UN she is not allowed to work, so she lost her job and her flat

Read more about Knud Vilby

The Danish government’s attempt to return a number of refugees who have earlier been granted asylum in Denmark is raising new questions regarding the legal rights of the individual refugee. Refugees end up in a situation where they on one hand are given permission to stay in Denmark but on the other hand are deprived of an income to support themselves. They end up on the street although they are legally allowed to stay here.

This is not about rejected asylum seekers, but about refugees who sought and were granted asylum, because the assessment at that time was that their claims were justified. They were given residence permits when their cases had been considered by the authorities, and they could therefore start their integration in Denmark.

Today, however, the authorities find that conditions in the countries of origin are so much better that they can be returned without any (major) risk. Their residence permits are therefore withdrawn, and they are typically asked to leave Denmark within 30 days.

Several of these cases have been appealed to the UN human rights committees, after both the Danish Immigration Service and the Refugee Appeals Board have decided to deprive the refugees of their residence permits. The UN has rejected most of the requests, but in some cases the arguments are strong enough to make the UN consider them. If that happens, the Immigration Service informs the refugee that he or she is allowed to stay in Denmark until the case has been finally decided. And this will often take up to 2 years.

But the rejection by the Refugees Appeals Board implies that the work permit and the right to receive social benefits is withdrawn, and these decisions are not altered. The refugee ends up in a limbo. He or she can stay because of the ongoing case but is not allowed to have an income.

A specific example is 32-year-old Fadima from Somalia. She fled from Somalia, where her father was killed, and where she was forcefully married to a member of the Al-Shabaab terrorist group. She fled from an area controlled by Al-Shabaab. She was granted asylum in 2014 and received a temporary residence permit.

Four years later, in 2018, Danish Immigration Service judged that her residence permit should be withdrawn because conditions in Somalia had improved. According to them, there was no longer an actual risk for her if she went back. The case was appealed to the Refugee Appeals Board, which in May 2019 agreed on the decision by Immigration Service.

Niels-Erik Hansen (lawyer specializing in asylum cases) has submitted the case of Fadima to be considered by United Nations Committee on elimination of all discrimination against women (CEDAW), arguing that there is a risk of gender specific victimization among other things because Fadima comes from an Al-Shabaab controlled area.

The Committee finds that the arguments against returning Fadima are strong enough to accept the case for specific and concrete procedure. And she has consequently been informed that she can stay in Denmark for as long as the processing of the committee takes. But without work permit or other options for economic support, maybe for years.

Fadima is not a rejected asylum seeker. She was granted asylum in 2014. She has not committed any offence against Danish law during the almost 6 years she has lived in Denmark. After a few years of internships and jobs as caretaker for children, a Danish employer had given her a job, but he will now risk a fine if he keeps her as an employee.

She has been deprived of all means to support her living. She has lost her work. She has lost her apartment, because she is unable to pay the rent. She is regularly spending her nights at a shelter for homeless women and she is seeking help from friends. Her access to doctor and health care is like an asylum seeker: only neccessary and acute help.

Ultimately, she may be forced to once again stay at an asylum center, but only with the purpose of spending the waiting time. For she is staying in Denmark legally for as long as it takes for the UN to deal with her case.

It is not known how many cases like Fadima's there are in Denmark, but her case is not the only one which has occurred after the immigration authorities' decision to revoke many residence permits and return refugees.

(Fadima is not the correct name, but I know the name and her case).

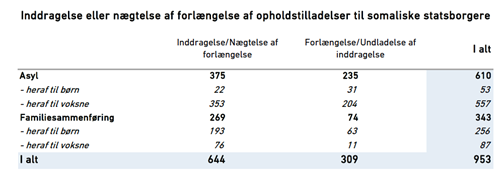

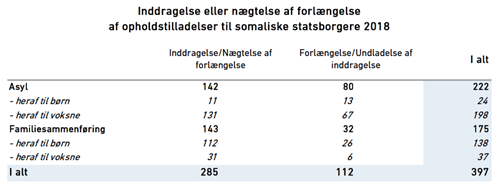

Fadima is one among more than 1,300 Somali refugees and family reunified persons to refugees who have had their permits revoked during 2017 and 2018. Numbers below from first instance (Immigration Service) and text extract from Immigration Service yearly report 2018 (only in Danish).

The Refugee Appeals Board, which is appeals body for these decisions, has a somewhat different attitude to the Somali withdrawal cases. So far, the board has decided in 458 cases, and the outcome was:

Confirmation: 212

Reversion: 91 (of these, 41 were because of attachment to Denmark)

Return to Immigration Service: 155

So, the board has disagreed with Immigration Service in more than half of thes cases. In other types of cases the board only reversed the decisions in 17% of them, in 2018.