The Refugee Appeals Board overrules Immigration Service decisions

Most Somalian and Syrian withdrawals of residence permits are overruled or sent back to the Immigration Service

FACTS:

When a refugee gets his or her residence permit withdrawn the Danish Immigration Service summons the individual for an interview, often in the presence of an interpreter, where the individual is asked about the original motive for seeking asylum, any new motives for seeking asylum, and about his or her connections to Denmark, both with respect to integration and family relations.

The case is decided upon by an academic employee (not necessarily a law graduate), which is working under the supervision of an office manager. These officials work directly under the current Integration Minister.

If the decision is that the residence permit should be withdrawn the case is automatically transferred to the Refugee Appeals Board, which is an appeal body. Here the applicant is assigned a lawyer, and the case is generally decided upon orally at a board meeting. The Refugee Appeals Board either agrees with the Immigration Service and confirms its decision, disagrees with the Service in which case the residence permit is given back, or asks the Service to process the case again.

The Refugee Appeals Board’s various parallell boards consist of three individuals: A judge, a lawyer appointed by the Law Council, and one individual appointed by the Integration Ministry.

The Refugee Appeals Board’s decisions are final and juridically overrule the decisions taken by the Immigration Service, in such a way that the Immigration Service has to align its practices with those of the Board.

One of the most discussed topics relating to refugees is that of returning to the origin country when the security situation has improved. Already in 2015, when the government was headed by Helle Thorning Schmidt, a law was passed which stipulates that a refugee’s residence permit may be withdrawn although there has not been any stable and lasting improvements in the home country.

This paradigm shift was seriously introduced in connection with the Finance Act Agreement in January 2019, where focus shifted from integration and opportunities for permanent residence to temporary permits and returns. Most experts agreed that this policy would not be possible to implement in reality, as the conditions that create refugees typically are long term and last several years.

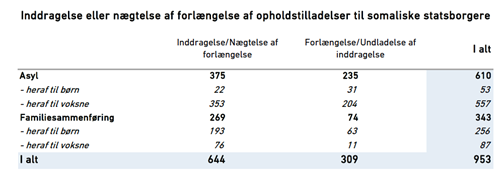

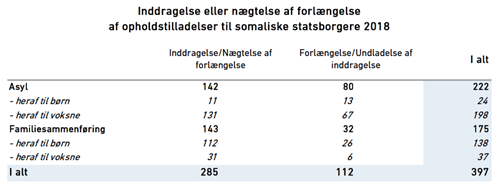

Somalia

The effect of the new legislation has so far been that many Somalian refugees have lost their residence permits, many after having spent 4-5 years legally in Denmark. This happened after 6 test cases had been processed by the Refugee Appeals Board, which had confirmed the Immigration Service’s decisions in all cases, although the reports serving as foundation for assessing the security situation in the country were criticised. Subsequently the Appeals Board has however overruled or sent back more than half of the in total 1.350 withdrawals (see tables from the Immigration Service below).

2017:

2018:

The Appeals Board has until now processed 458 out of in total 1.350 cases, with the following results:

Confirmation of the Immigration Service’s decision: 212

Overruling the Immigration Service’s decision: 91 (whereof 41 decisions were overruled based on the individual’s connections to Denmark)

Cases sent back to the Immigration Service: 155

In effect, the Appeals Board has disagreed with the Immigration Service in more than half of its decisions regarding withdrawal of residence permits. For other types of cases during 2018 the Appeals Board disagreed with the Service in only 17% of the cases.

Syria

This summer the Immigration Service tried again with a new group: Syrian refugees from Damascus holding temporary §7,3 residence permits — this again with reference to a report describing security improvements. This time the Appeals Board very surprisingly overruled all 6 test cases and moreover assigned all 6 individuals asylum statuses according to §7,2 or §7,1.

The Appeals Board has in the 6 cases not taken a stance on whether the general conditions in Damascus have improved, but decided that the following reasons are cause for protection:

• Close family members of individuals with special risk profiles, including people who have avoided their military service or similar, or who because of other reasons are perceived as being in opposition to the Syrian authorities

• Individuals stemming from, or who have stayed in, areas which previously were controlled by the opposition

• Public servants who have left their position without prior permission

• Individuals who in one way or another have been exposed as opponents of the Syrian regime (for instance via media exposure in their country of asylum)

Read a summary of the cases here (in Danish)

Serious consequences

The two situations above can be seen as a general disapproval of the way the Immigration Service works, which is problematic. The 6 Syrians and the adults among the 1.350 Somalians had all been summoned to a new interview in connection with the withdrawal of their permits, where they hopefully were asked about any new motives for asylum.

In all Syrian cases the Appeals Board found new motives for asylum. In 20% of the Somalian cases the Appeals Board deemed that the individual still was in need of protection, or that his or her attachment to Denmark was so strong that he or she could not be returned. In both situations the cases had been evaluated differently by the Service just shortly before. Even more of the Somalian cases were sent back to the Service, which in practice means: do your work properly, take a look at these cases again. The Immigration Service has previously been criticised for not taking into account children’s asylum motives, but has assured that during the past years children have been asked this directly during interviews with parents. Nevertheless the Appeals Board has found new asylum motives, including risk for circumcision of children in many Somalian cases — and in all Syrian cases there was an individual motive that the Service apparently had not found.

Concerning withdrawal cases the Appeals Board thus disagrees with the Immigration Service in 6 out of 6 Syrian cases, and 246 out of 458 Somalian cases. This should be reason enough for self-introspection by the Service, and hopefully also by the politicians who should realise that it is not realistic to send refugees home after only a few years — and that the new focus on temporality and returns is a failed policy which only serves to undermine integration efforts.

Residence permits should only be withdrawn when there are very compelling reasons for doing so and when the case has been evaluated carefully. To send an individual home is a violent and intrusive change in that individual’s life — emotionally this creates anxiety and may cause or reactivate traumas. Practically it also places the individual (and possibly also his or her family) in a legal limbo, as formally the residence permit is withdrawn while one awaits the decision of the appeal. The rights to work, receive benefits and study are immediately lost. A complaint to the Appeals Board may however have a suspensory effect on these matters until a final decision has been made.

Read the story of Fadima: Refugees forced to live on the street despite legal residence

Read more about the Syrian test cases here

Read more about the Somali cases here (update from 2018)