Questionable test determines the age of refugee minors

An increasing number of age determination tests are being carried out on unaccompanied refugee minors. The test is based on probability but has definitive consequences.

So far this year, 800 tests to determine the age of unaccompanied refugee minors have been carried out by the Department of Forensic Medicine. This is twice as many as last year, despite the fact that only half as many unaccompanied minors have arrived during 2016. Many of those who have been tested this year, actually arrived last year when there was an increase in the tendency for the arrival of the very young children without parents. In 2014, 815 unaccompanied refugee minors came to Denmark and only 292 were tested to determine their age.

This could suggest an altered and intensified practice, even though the Danish Immigration Service maintains that they only carry out the test if there are suspicions that the person could be over 18 years of age. The increase can also partly be explained by the fact that the Department for Forensic Medicine has increased its capacity to carry out the examination. However, a representative from the Danish Red Cross, who wishes to remain anonymous, has related that all unaccompanied minors are now being age-tested, unless they are obviously very young or have documents that prove their age. Only a minority have these.

The test’s results lead to the Immigration Service changing the age of ca. 70% of the minors that are tested to being over 18. Here, it is important to remember that the youngest are not tested – and that children as young as 7 arrive without their parents.

A new practice, just announced by the Immigration Service, will see all unaccompanied minors, who are judged to be 17 years old being placed in adult centres rather than the special children’s centres they would normally be placed in. At the moment, ca. 700 individuals are residing at children’s centres, and 220 of these are registered as being 17 years of age. They will now be moved to ordinary asylum centres, where they will share rooms with adults and where they will be without the special support they received at the children’s centres.

Uncertain results

The actual test method is unreliable and has been the subject of criticism throughout the years. On top of this, it’s up to the Immigration Service to interpret the result, which has extremely serious consequences for the youths in question. Often, the test is first carried out after a minor has been residing in children’s centre for several months, or in some cases, for up to a year.

The test is based on three elements: a doctor examines the undressed youth’s body, x-rays are taken of their teeth, and of the bones in their hands. On the basis of these three things – in particular, the x-ray of the hands – a written statement is made with an assessment of probable age. The method is known as the Greulich & Pyle method and was developed in the USA during the 1950s.

A professional representative from the Red Cross explains that the dentists who carry out the x-rays stop at the least resistance from the child – and the case is then determined without the x-ray. Many of the children have never been to a dentist before and are very nervous. The doctor examination where the child’s body has to be seen completely naked is also an affront for many – attempts are made to use doctors of the same sex but this cannot be guaranteed.

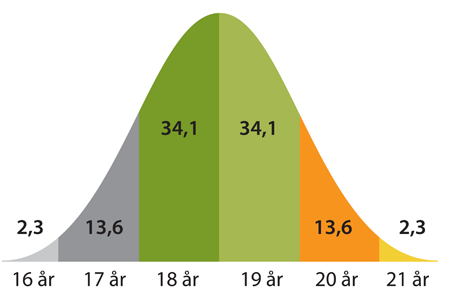

An example of an assessment of probable age (in percent)

In the graph shown above, the most probable age is 18-19 years of age (in total, 68.2% probability). There is 13.6% probability that the youth in question might be 17 or 20 years of age. Here, the Immigration Service will typically register him as being 18 years of age – the lowest of the most probable numbers. However, as the graph shows, it is a fluid curve and some of those tested will by necessity find themselves in the less probable areas. Therefore, it is inevitable that some minors will end up being treated as adults, which is illegal.

The Red Cross representative recounted a recent case where two sisters were sent to have their ages assessed. They had recounted that there was two and a half years between them. After the examination, the eldest sister was determined to be 18 and the little sister 19 – i.e. the big sister was suddenly the little sister. Although some individuals may have an interest in lying to make themselves seem younger, it’s difficult to imagine why two siblings would intentionally try to swap their ages. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to see documentation from this case as both sisters have since been moved to adult centres and are therefore no longer in contact with their representative.

The Department of Forensic Medicine has also stated themselves that their examination shouldn’t stand alone – yet it does in almost every case. The Danish Refugee Council, Red Barnet and Refugees Welcome therefore call for a supplementary examination, where the child’s maturity is gauged based on psycho-social parameters.

The Danish lawyer Jens Bruhn-Petersen took a case to High Court in 2009, and the court agreed that his Afghan client might be under 18 years when he applied for family reunification with his mother in Denmark – in spite of the age test showing a 84% probabilty that he was over 18. The court found other facts in the case as important. But this option is not available for the unaccompanied minors, when the age test stands alone.

So far, Sweden has rejected the examination method used in Denmark as it was deemed too unreliable. However, this year, it was decided that 15-18,000 unaccompanied minors in Sweden would be examined using a new method. It is based on x-rays of teeth and knees and the Swedish authorities deem it to be more reliable.

Missing documentation

There’s no doubt that some of the minors who claim to be under 18 are, in fact, over 18. However, it’s also a fact that many of the asylum seekers from Africa and Afghanistan don’t know precisely when they were born. Birthdays are not celebrated as we do in the West and you don’t get an official document when a child is born. Children are often only registered for the first time when they start school.

The majority of unaccompanied minors arrive without any form of documentation, and there can be many reasons for this. Many have never had an ID-document, such as many of the Afghan boys who grew up as illegal refugees in Iran and Pakistan. Others have lost them during their flight, such as those forced to hand them over to smugglers and still others have thrown them away intentionally with a view to pretending to be younger. Other ID-documents are not officially recognised in Denmark as they are too easy to forge. This generally applies to all documents from Afghanistan and it’s precisely here the majority of unaccompanied minors come from. And even if a teenager from Eritrea does manage to acquire their birth certificate and have it sent to Denmark, it will normally not be accepted as proof of the child’s age.

Great consequences

The biggest problem is that a test, which has such a large margin for uncertainty, can have such a decisive impact on the young. The first consequence is that a youth over the age of 18 can be sent to another land under the Dublin Agreement, if s/he has had their fingerprint taken there. Many have provided fingerprints in Italy, where the conditions they are accommodated under are inadequate and objectionable, or in Hungary or Bulgaria, where no accommodation is provided at all and where the asylum procedures are utterly unacceptable.

If the youths haven’t provided a fingerprint in another country, and are granted permission to have their cases handled in Denmark, their stay in an adult centre will be markedly different from that in a centre for children. Centres for children are typically quite small and located in smaller towns. They are manned 24 hours a day, often by staff with pedagogical backgrounds. The children reside two to a room, go to school every day, are involved in making food and can avail of a range of sport and hobby activities. Many children are also in contact with a psychologist. The adult centres on the other hand are much bigger, with up to 600 residents of all ages, and a single man will often share a room with three to four others. Some centres have canteens rather than kitchen facilities and access to school and other activities is very limited.

The actual asylum application and the chances of being granted residency also change with an age determination of over 18 years. The right to having a representative present during interviews stops and the fact that children can have difficulty in relating and explaining their backgrounds is no longer taken into account. Processing time for cases concerning minors should - in theory - be quicker, but this is not always the case. At the moment, 300 unaccompanied minors have waited a full year for an answer, and many are first sent for an age assessment after a year of waiting. Minors also have an extra chance of being granted a residency permit (§9c stk 3,2) if the child has no family-based network back in their homeland, but this residency permit expires once they turn 18.

Even those who are granted residency can expect a great difference between arriving in their new local council as an unaccompanied minor or as a single adult over 18. Local councils have special responsibility in terms of minors, who will be offered accommodation in either sheltered accommodation, an institution or with a foster family, depending on their maturity and wishes. Here, they will get support and help to get up in the mornings, do homework, make food, choose clothes etc., and will be accompanied to meetings and appointments. A temporary guardian will be appointed by the State Administration, the local council will provide two social workers to each child and hold regular meetings with schools and places of residence. Normally, the child will be enrolled in an ‘integration class’ at school and offered sport and other leisure activities.

On the other hand, an 18-19 year old who arrives to a local council will typically be lodged in a temporary residence together with other refugees. He’ll be given the very low integration benefit and go to language school ca. 12 hours a week, supplemented with unpaid work experience for up to 37 hours a week. No social supports and the only meetings are with the job centre every third month.

For the Syrian children, there’s an even more important difference: if they are under 18, they can apply for family reunification for their parents and younger siblings. In practice, however, very few children over 16 are granted permission for this.

For the very young children, it has a kind of backwards consequence: if the Immigration Service judge a child to be too immature to go through the asylum process, they will then wait until the child is old enough. For example, a 9 year old girl has been told she must wait until she turns 12. Previously, residency was granted after the paragraph for exceptional circumstances (§9c stk 3,1) in these types of cases. As long as she doesn’t have residency, she can’t apply for family reunification with her parents.

Give them the benefit of the doubt

The Immigration Service claims that they give the children the benefit of the doubt in that they choose the lowest of the most likely ages. But the test itself is for the first, not scientifically reliable, and there is also a risk that the minor should actually be positioned in the more improbable end of the spectrum. This will inevitably lead to some children being treated as adults under Danish practice, and this is illegal. The lack of assessment of the minor’s mental state and maturity is also a problem, as some very vulnerable minors can be placed in situations that they are not able to handle.

The UNHCR recommends that the EU should come to an agreement concerning a common, holistic method and that children should be given the benefit of the doubt.

The very sharp and black-and-white line that is drawn between being over and under 18 can seem so artificial when you see a group of teenagers at a centre for children – their maturity and mental health can be so different, but they are fundamentally all in the same situation. Many of them were on the run for several years before they arrived here and were, therefore, without a doubt, children at the time they were forced to leave their parents and their homelands.

Best interest of the child

Danish practice works after the model of ‘the greatest probability’ when determining age, which by design leads to a small percentage of children being mistakenly treated as adults. 17 year old unaccompanied minors have to live at adult centres, children lose their residency visas in Denmark when they turn 18 (if they have been granted one due to lack of network in their home country) and very young children can’t get residency, and thereby the right to family reunification because they are too immature to go through the asylum process. None of these conditions sit well with the demands stated in the Convention on Children’s Rights that the interests of the child must always be given the greatest weight in all decisions concerning children.

Asylum or residency on humanitarian grounds?

The unaccompanied minors from Syria and Eritrea are granted asylum, just like their adult countrymen. But the young Afghans, who make up the majority of unaccompanied minors, are very rarely granted residency. They are not deemed individually to be at great enough risk and likewise the general state of their homeland is not deemed to be sufficiently critical. However, common for them all is the fact that they’ve been through very traumatic experiences and that they have been forced to leave the world they knew all too soon. When the young are deported back to Afghanistan, they are in a profound emergency situation: they often have no remaining family, they have no means to live by and have lost their self-confidence and hope for the future. There is no follow-up investigation to see what happens after they are sent back, but some of the few for whom there is information have ended up on the street (one individual was even killed shortly after returning), in camps for internally displaced people or have fled to neighbouring countries.

It is no longer Danish practice to give residency on humanitarian grounds: over time, that has been restricted to those with life-threatening illness. Report in English on this issue here.