The road to freedom goes through Hell

In August 2014, Simon and his wife Ghenet put their lives in the hands of human smugglers. Their hope was a free life in Europe. This is his story.

After I was released from prison in 2010, I married Ghenet. She had been by my side through everything, and I loved her very much. I had ended up in prison because I had deserted after two years in military service. In Eritrea, as an ordinary citizen you have to do your service for the state, so after military service I was supposed to continue civil service. But I did not want that, we wanted a normal life, and we succeeded in putting up a shop, though that is a difficult thing to do in Eritrea. My wife was in charge of the shop and I helped her during weekends, but apart from that I could not work, because the state wanted me to work for them.

It was a difficult life, and may times over the years I wanted to flee from my country. But then I would put my destiny into the hands of unscrupulous human smugglers? Maybe I would end up as a hostage and they would demand money for me? Maybe they would sell my organs? Ten years passed like this. Ten years where I was optimistic about the situation of the country – things would be better. But every time things got worse.

In the end I could not see any way out, and I decided to flee.

The dictator of Eritrea, Issayas Afwerik, had been ruling the country for two decades at that time. I was supposed to go back into military service once again, and the army gave me a Kalashnikov. Even elder men of 70 year were obliged. I had had enough. So I decide to of to the neighbor country Sudan. The flight was dangerous, I had to avoid the militia working with the government. If I was caught, I would end up i prison again. But I took the chance, and I succeeded.

All photos are private, taken by Eritrean refugees in Denmark

Thousands of dollars for a trip to Hell

In Sudan I had a little of my freedom back, but it was only a limited time. It is estimated that 100,000 Eritreans are living in Sudan, but you will not get a status of refugee, and if the authorities find you, they will imprison you and send you back to Eritrea. Corruption is the core of the Sudanese society. The police will demand money from you, but ordinary people will too. I have been stopped by a 12 year old boy who kept shouting “habesha, habesha…” which means that we are different from them. We not only don’t speak their language, we also look different and we are Christians.

I lived in Sudan with my younger brother and sister, who had also escaped from Eritrea., and after one year my wife Ghenet left everything we had and also came to Sudan. The authorities had started asking for me, and she no longer felt safe. But life was hard in Sudan, and every day a fight for survival, so after seven months Ghenet and I decided to take the dangerous trip through Sahara and across the Mediterranean to Europe.

For years I had warned people not to take that trip. “It’s dangerous. You pay thousands of dollars to end up in Hell” I had told them. But we had no choice, if we wanted to live freely and in a democracy.

Unscrupulous smugglers

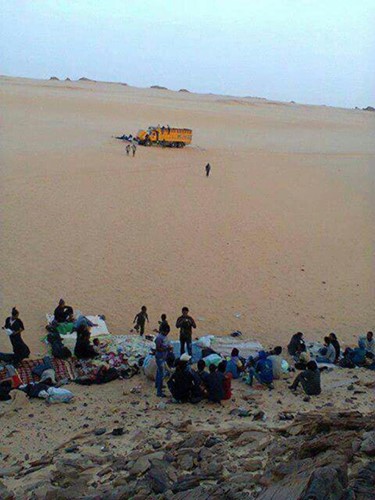

The second week of August 2014 Ghenet and I began our journey. Many young Eritreans, but also people from Somalia, Ethiopia and Sudan accompanied us on the journey. We showed the Sudanese human smugglers that we had 2,000 dollars for the trip, and in the middle of the night we were put in a truck.

But already in the outskirts of Khartoum we were stopped by soldiers. They searched us and took what we had, including my wedding ring of gold. Ghenet was smart enough to take off hers and keep it in her mouth – I am sorry that I did not do the same. But as usual, they were just after our belongings and let us continue.

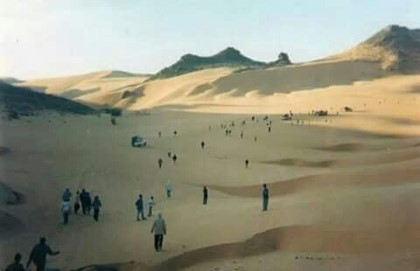

We drove through the desert for four days without resting. The smugglers used the compass in their mobile phones, because in Sahara there are no roads, so otherwise it is impossible to find the way.

When we reached Libya the Sudanese smugglers gave us to some Libyan ones. Once you gave yourself over to the smugglers, you are their possession. You will no longer be seen as a human being, but as cargo that needs to be transported from one

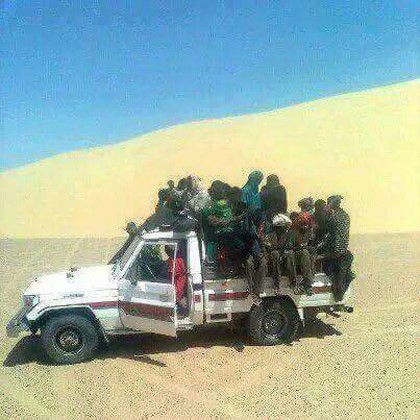

30 in each pickup van

When we arrived in Libya, at last we got a short rest. The smugglers had to eat and trade what they had – among other things a flat screen TV – and when they were done, we were loaded on board again. This time onto three Toyota pickup vans. We were at least 30 on each van, and there was no from for our bags where we had food, water and basic necessities. “If you want to go to Paradise, you must leave them here”, they told us. They put the women in the middle of the vans and the men on the rim – if anybody got sick or fell off, it was just too bad.

The smugglers had taken drugs. With a speed of 150 km/h they drove nonstop through the last part of the Sahara. No breaks, no food, no drinking. It was incredibly hot and endlessly flat, and for three days there was nothing green as far as you could see.

After three days we arrived at Elzabaya and we were sent into a large warehouse with at least another 100 refugees. We were supposed ti stay here for one month, and the only thing we had to eat was a little bread.

We were lucky

The sound of shootings was constant, and I was taken aback by my emotions. What had I done? This was what I had always tried to avoid, and now I was in it nonetheless, in a country totally destroyed by civil war. But there was no turning back now, and I got a hold of myself.

The journey to the Mediterranean coast went through Tripoli where intense fighting was going on. 100 of us were “luck” enough to be transported through – the ones who had another 2,000 dollars for the trip across the sea to Italy. The journey took 12 hours, crammed inside the middle of a truck full of sacks with animal food. We passed ten check points. If we were caught, we would end up in prison. Incredibly, we made it and we were put off on a beach. Here we had to hide for two weeks until the smugglers who were supposed to take over, came.

Sometimes I think that we survived against all odds. We were 500 on board the small boat. We were afraid of the Libyan navy, the human smugglers whoi came from different groups, and of the ea. The refuges were fighting over the food and water. “Let this end well”, Ghenet and I prayed to God, “let us survive this”.

And God hear our prayers. After 15 hours on the small boat we were rescued. We arrived to Europe.

On train to Denmark

We were lucky. It was the Italian coast guard who rescued us. We had ended up in the south of Italy near the coast of Sicily, and after another 15 hours on the skip of the coast guard we reached the big island. Some humanitarian organizations received us and installed Ghenet and me in a hotel.

We had no idea about where to go. Most of the other people installed in the hotel left shortly after, to avoid having fingerprints taken in Italy. But I didn’t care, and at that time I saw no problem in that. The only thing I could think about was being alive, and grateful to be a survivor.

Some young refugees who were now living in Italy helped us for a fee to have money transferred so we could buy a train ticket for Milano. And after three days we left for the Italian city. We had still not had our fingerprints taken, and we decided to head on to Denmark.

We had heard that in countries like Denmark, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and Norway, Eritreans got asylum. So we took the train from Milano to Germany and from there to Copenhagen, where we went directly to the police station and asked for asylum.

The Danish language is a challenge

Ghenet and I were sent to a Red Cross asylum center in Jelling, where we ended up waiting for 7 months. We did not know our destiny, but got confused when we saw that people who arrived after us got asylum. But I liked the Red Cross staff members. Their work was meaningful in my eyes, they were true to their values and were decent people, they did what they could to make our stay pleasant by arranging courses and activities. This made me happy after having seen the lack of respect for human life from the smugglers, but also from the authorities of my home country.

It turned out to be the Eritrea report (by Danish Immigration Service, ed.) which was the cause for the delay of our cases, and two months ago (May 2015, ed.) Ghenet and I had a positive answer. Now we have started our new life. We moved to Favrskov and already we have lots of Danish friends. The biggest challenge is the Danish language which is hard, but fortunately I speak English. I love our new life, and I am touched by the Danish hospitality that we meet everywhere. Now I am just looking forward to finding a job.

Then I can start paying back to Denmark.

Often I think about Eritrea and the many people living under the dictatorship. I survived prison and the escape, which many people didn’t. But you can not imprison a free soul, and I think I ended up surviving because I have always believed that the worst prison is your own conscience.

Glossary – National Service

In Eritrea, all citizens, men and women, are called in for National Service, a kind of mandatory civil work beside the military service. The work can be anything from teaching to prison guard to mining. The laws says it takes 18 months, but in practice there is no end date, and some have been there more than 10 years. Escaping will result in years of prison. There is no court system in Eritrea.