Great disparity in asylum assessment

Denmark, Sweden and Germany are at odds in terms of how the same asylum case should be assessed

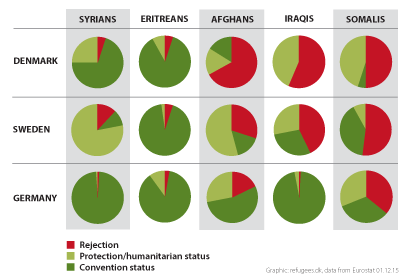

The graph shows enormous differences between how asylum cases are assessed in Denmark and in our neighbouring countries: not just the chance of being granted asylum, but also which status applicants are granted. Choice of status is important, because convention status gives access to a more secure form of residency visa – often for a longer period of time and with more rights attached.

Asylum decisions (first instance) 3. quarter 2015

There are large differences within this area internally across Europe and it has long created difficulties in relation to the Dublin Agreement, which means that registration with the first fingerprint becomes a lottery. It is also a substantial problem when the EU attempts to reach an agreement on the allocation of asylum-seekers. It’s difficult to see how any allocation can be considered fair, unless countries also become more consistent in terms of their assessment of asylum cases (read more: EDITORIAL: A solution model for refugees in EU)

An Iraqi citizen has a 43% chance of being granted asylum in Denmark and a 99% chance in Germany. An Afghan citizen has a 67% risk of rejection in Denmark and just 18% in Germany.

A Somali citizen has roughly the same chances of getting asylum in both Sweden and Denmark – however, in Sweden he’ll be granted convention status, not so in Denmark. This is the reverse of the situation for Syrians, who have a 70% chance of getting convention status in Denmark but just a 10% chance in Sweden.

The only country about which there appears to be agreement is Eritrea. Here, the picture is largely consistent across Europe: on average, 96% get asylum and out of these, 70 – 100% get convention status. There is also agreement on giving asylum to almost all Syrians, but their eventual status varies to an astonishing degree.

FACTS: Convention status (in Denmark §7,1) is the strongest form of protection that can be given to people who are persecuted, as defined in the UN’s Refugee Convention. However, there are also other forms for subsidiary protection. These can be granted in the case of people who risk the death penalty, torture or other inhumane treatment, as described in the European Convention on Human Rights and the UN’s Convention against Torture, and as such, come under the Danish Aliens Act §7,2 or the new §7,3 (1 year protection status). The latter is so far only granted to Syrian citizens (ca. 20% of them). Furthermore, residency can also be granted on a humanitarian basis, which is regularly used in some European countries, but very rarely in Denmark.

Disagreement on status

In Denmark, the majority of Syrians and almost all Eritreans are granted convention status, due to forced military/national service and desertion. Somalis and Iraqis are rarely granted asylum as defined by the Refugee Convention, but are typically granted a weaker form of protection status.

There will always be a degree of variation in terms of practice in the area of asylum, from country to country, but it is notable to see such a great disparity between three countries, which are otherwise similar in many other areas. Such great differences are not just an expression of a harder or softer line in relation to credibility in individual cases, but also reflect vastly different interpretations of the situation in the respective homelands. If you look at each nationality, the applicants’ stories are often broadly similar: roughly speaking, Syrians flee from war and military service, Eritreans from endless national service and oppression, and Afghans from the Taliban and private conflicts.

Eva Singer, Head of Asylum in the Danish Refugee Council, explains that the disparity in the assessment of cases among our neighbouring countries has always been great. Among legal professionals, there is disagreement about how to assess persecution in relation to the Refugee Convention. Singer relates that Germany has changed its practice in relation to Syrians. Previously, if they had deserted from military service, they were granted protection status, now, they get convention status. Military service is not in and of itself a guarantee of asylum, but it can lead to asylum in cases where said military service will involve being forced to commit human rights abuses. Eritreans are typically granted convention status everywhere, because in addition to their military service, they are also under threat of punishment for ‘desertion of the state’ – i.e. having left the country illegally.

Another cause for disagreement is the ‘agents of persecution’: those, who are doing the persecuting. It can be anything from the state authorities, as in Eritrea and Iran, but it can also be a strong group, which the authorities cannot protect the asylum-seeker from, or which have outright taken control of a country, such as Al-Shabaab in Somalia, the Taliban in Afghanistan or IS in Iraq. Here, it seems that the European countries disagree most over whether or not persecution is covered by the Refugee Convention. However, it is also surprising that that the same European countries also have vastly differing views in terms of the persecutors. For example, Sweden gives convention status to the majority of Somalis, but to very few Afghans, despite the fact that both Al-Shabaab and Taliban are both strong forces, which actually have control of large parts of the respective countries.

Sweden’s reputation

Based on these figures, one can perhaps wonder why Sweden has the reputation as being the best asylum country in Europe. For all of the main groups of of asylum seekers, the chances of being granted asylum are higher in Germany than in Sweden, and for the majority, the chances of getting convention status are greater there. For Syrians, it’s actually better to aim for Denmark, unless you fall under the 20% who are affected by the 1-year §7,3.

According to Sanna Vestin, spokeswoman for the Swedish umbrella organisation FARR, for many years, Sweden has only awarded convention status to a very small proportion of asylum-seekers. Syrian military service or desertion is generally not regarded as ‘persecution’. However, the number of asylum-seekers being granted convention status is increasing, particularly for Afghans, and Vestin sees this as being connected with the EU’s Qualification Directive.

The Swedish government have announced new restrictions, which mean that all those without convention status will not have any right to family reunification. These restrictions have not yet been enacted however, and there is uncertainty about whether or not they actually will be. Sweden will also cut back on the granting of visas on the basis of humanitarian grounds and this would mean the rejection of many unaccompanied minors from Afghanistan, who typically would have been granted humanitarian residency in Sweden.

Asylum-seekers rarely pay much heed to these complicated and changing statistics. The majority aim for the countries where they have family, or where they feel the opportunities for access to work and education are good, or which have a reputation as being welcoming to refugees. In Italy, the chance of getting asylum is great, but refugees have extreme difficulties when it comes to finding work and a place to live, and Africans in particular often experience racist behaviour, therefore making Italy an unpopular country among asylum-seekers.

Note: The figures for Denmark are taken from Eurostat and do not exactly match those released by the the Danish Immigration Service for the same period. This can be due to different start points in collation of the figures. The largest disparity is for Afghanistan, where the percentage of recognition according to the Immigration Service is 52% and not 33% as shown in the graph.