New practice: Somalis lose residence permits after 4 years

The authorities are adopting a new line, that asylum may not necessarily be extended; five Somali cases may be only the beginning

Photo by Gerd Gottlieb: Thank you party held by Somalis in Sandholm after receiving asylum in 2012

UPDATE 13.10.2016: Danish Immigration Service informs that the 1,200 cases to be screened cover 1,450 persons (of these 165 school seeking children). Of these, ca. 220 have been granted asylum (7,2) first time between 2002-2011 and have had the permits extended afterwards. The remaining ca. 1,230 persons have been granted asylum (7,2 or 7,3) first time in 2012 and onwards. Persons who have had their permits extended after 20.02.2016 will not be part of the screening.

Some Somali refugees in Denmark now risk losing their residence permits. In 2012, Denmark was forced to align its practice with a judgment by the European Court of Human Rights. It was the so-called Sufi and Elmi judgment, which said that the overall situation in Mogadishu was so dangerous that everyone coming from there should have protection. But now the Danish Refugee Appeals Board has expelled five Somali refugees (link to text in Danish), referring to recent reports of improved security in Mogadishu.

Serious consequences

Ninety-one Somalis who had been rejected for asylum were subsequently granted residence permits in 2012 on the basis of the judgement. Later, many of them were permitted to have family members join them in Denmark under family reunification rules. Some of the ninety-one residence permits expired after 4 years, and the Danish Immigration Service recently decided to refuse to extend them. The final decision on five selected test cases passed to the Refugee Appeals Board, which found by a majority that the security situation in the subjects' home region was significantly improved.

The Sufi and Elmi judgment had only a short-term impact, because already in February 2013, the Danish Immigration Service began again to refuse asylum to almost every second new applicant. But withdrawing a residence permit is a much more drastic step, because here the burden of proof moves to the authorities: are there concrete improvements in the home situation which means that the case must be looked at completely differently? The Refugee Appeals Board's reasoning is not clear from their new decisions, which mention reports of both improvement and deterioration.

The Danish Immigration Service has indicated that it will screen 1,200 Somali cases (link to text in Danish) to see if the home conditions played a sufficiently significant role in determining the grant of residence permits to them. Those affected will receive a letter and their cases will go to a hearing. Unless they have a particularly strong attachment to Denmark for other reasons, they risk being expelled from the country.

The question is what will happen to those who are denied extensions to their residence permits. So far, the only prospect seems to be that they will be required to move from their Danish municipalities, schools and workplaces back into asylum centres, mainly the removal centre, Kærshovedgård. It has been many years since rejected asylum seekers were sent back to Somalia. The last attempt, in May 2015, went wrong: the Somali authorities denied having accepted the entry of the four men, who were flown in by helicopter. It is unclear what happened to the men and the Danish authorities have not made any public confirmation. Recently, the Danish authorities made another attempt, which was foiled because the plane's captain refused to include a Somali who resisted travelling. There are already 150 Somalis awaiting expulsion from Denmark.

Attachment to Denmark

Just four years of legal residence is not long enough to apply for permanent residence; currently six years of residence is required, and the government plans to increase this to eight years. Matters such as education, self-reliance, Danish language skills, etc, may not be considered until the full time requirements have been met, and even then few Somalis will be able to meet all the requirements for permanent residence.

Many Somali children were able to gain family reunification in Denmark, but now risk being expelled together with their parents. For children, the requirement is usually six to seven years of legal residence in Denmark, for it to count as an independent attachment to Denmark.

Last year the organisation Refugees Welcome sought permission to stay under the Convention on the Rights of the Child for a number of children from different countries, all of whom had spent between five and ten years in Danish asylum centres after having had their asylum claims rejected. The permits were refused on the grounds that they had resided illegally and that it was their parents' responsibility that they had been so many years in Denmark.

Humanitarian considerations are not often given weight in Denmark anymore. Last year, only 25 people received 'humanitarian residence' under section 9b of the Aliens Act, and it was due to their having life-threatening diseases which could not be treated in their home countries.

Differences in asylum status

There are three different ways to get asylum in Denmark, ie three different statuses:

• 'Convention status' under section 7 (1) of the Aliens Act. This is the strongest status, coming directly from the UN Refugee Convention. The Convention requires 'fundamental, stable and durable change' in the refugee's home country before the authorities can consider withdrawing a residence permit.

• 'Protection status' under section 7 (2) of the Aliens Act. Individual protection status' refers to other conventions signed by Denmark - in particular Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which prohibits torture and other inhuman treatment or punishment. It is this status, which virtually all Somalis have.

• 'Temporary protection status' under section 7(3) of the Aliens Act. This third status was added in 2014. It is a weaker protection status, only aimed at the general situation in the country of origin. It was designed for the Syrian refugees who are not individually persecuted, yet cannot be returned. In practice, it is used mostly for women, unaccompanied minors and older men. If section 7(3) status had been introduced before 2012, it is likely that many Somalis would have received it. In 2015, five Somalis did receive section 7(3) status.

In November 2015, the Danish government shortened the term of section 7(1) and (2) statuses, which until then had both been given for 4 or 5 years initially. Now Convention status is valid only for two years, while both section 7(2) and section 7(3) protection statuses are each valid for only one year.

The six years of temporary residence required before one can apply for permanent residence (which is likely soon to be increased to eight years), along with very high standards of proficiency in Danish language and the requirement to be in full-time work, mean that the ability to stay in Denmark as a refugee hangs by a thread. This is a new situation, because refugees in Denmark previously received the right to permanent residence automatically after a number of years.

If protective status may be withdrawn without the existence of a stable and lasting improvement in the home country, this makes an untenable situation for refugees, who may receive asylum one month and have it withdrawn the following month. Here it is also important to remember that half the world's refugees are children, who have a special claim to security.

In principle, similar policies could be applied in the future to other refugee groups, such as Afghans and Iraqis. The Danish People's Party has long sought that refugees should not be integrated, and sent home as soon as possible.

Situation in Somalia

Since war broke out in Somalia in 1991, there have been many changes in the situation, but no stable peace periods. 20% of Somalia's population has fled the country. Somalia has for many years been top of the list of dangerous countries and failed states. The Danish Foreign Ministry warns against all travel there, and presently describes the condition of the capital, Mogadishu, as 'war-like'.

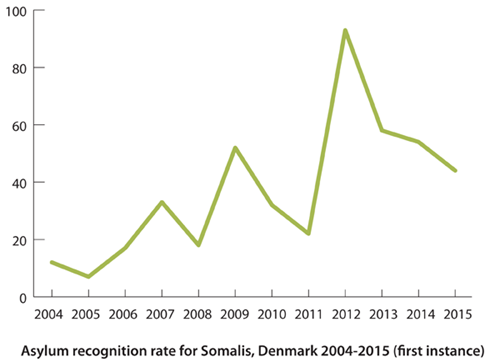

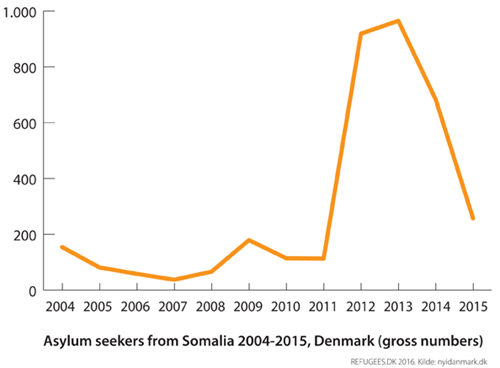

The Danish authorities have over the years found it difficult to make a firm position in regard to asylum-seekers from Somalia. In the 1990s, Somalis gained asylum almost automatically if they belonged to one of the smaller clans, but since then the share of positive decisions for asylum has varied between 7% in 2005 and 52% in 2009. The number of asylum seekers from Somalia has also varied widely, from ten persons in 2008 to 965 in 2013.

A man who was granted asylum in March 2016 has just received a letter that his residence permit will now be withdrawn. According to his lawyer, Hannah Krog, it is quite inexplicable that his position should have changed so quickly. Hannah Krogh has also handled several of the five new test cases, and she is appalled by the decisions. According to the lawyer, the Somali cases are dealt with strangely overall. In 2015, 44% of Somalis seeking asylum here got it, typically if they came from areas controlled by al-Shabaab. But this position changed suddenly in April 2016, when the Refugee Appeals Board began to refer to the flight options within the country in order to reject asylum claims, without having (as is the usual process) selected a number of test cases.

The Refugee Appeals Board wrote in one of their new decisions: "Looking, however, additionally at the Lifos Country Report: Somalia [...] of June 16, 2016 - this is for the Board the latest background information - including that al-Shabaab is at present just outside towns, including Mogadishu, from where they infiltrate the towns, mainly at night [...]. It also appears that the overall security situation in Mogadishu has deteriorated since 2015 and that al-Shabaab, which now carries out several attacks against large towns, increasingly makes its attacks against civilian targets. However, after an overall assessment of the background information, the Refugee Appeals Board majority finds that the overall situation in Mogadishu has improved – although the situation continues to be serious and must be characterised as fragile and unpredictable – just like the changes are not quite temporary in character. The majority of the Refugee Appeals Board takes the view that the removal of the complainant to Mogadishu no longer constitutes a violation of Denmark's international obligations, including Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights."

The Sufi and Elmi judgment was far from only based on the overall risk in Mogadishu, but also on the risk that those who had stayed a long time in the West would be particularly exposed to harm from the Islamist al-Shabaab movement, and who, without close family relationships, risked ending up in refugee camps under unacceptable conditions.

The European Court of Human Rights believed that all this would constitute a violation of Article 3 ECHR. But these considerations are not even mentioned in the new decisions from the Refugee Appeals Board, two of which are published here in anonymous form, in Danish (and two others can read under 'Praksis') – even though they could be said to be very relevant.

Many of the Somalis who were granted asylum in 2012 because of the Sufi and Elmi judgment had already spent several years in the asylum centres as rejected asylum seekers. Most Somali families are scattered, so many of those who have now been rejected have no family network to return to. And in a failed state which has been at war for over 20 years, one cannot expect support from anyone other than family. A serious humanitarian situation can in itself constitute a violation of human rights, such as would be covered by the Sufi and Elmi judgment.

Problems with integration

The constant threat of losing their residence permits will hamper the integration efforts of both the refugees themselves and of local authorities and businesses. The motivation to learn the language, find a job, continue in education, start a business, get acquainted with the community, etc, is weakened when you do not know whether you will be able to stay.

Somalis belong already among the immigrants/ refugees who are least assimilated and least likely to be self-supporting. Only 26% of Somalis living in Denmark are in work. It seems as though this may be hidden factors in the assessment of the risk to them. According to Statistics Denmark, there are 11,900 Somali immigrants and 8,900 of their descendants in Denmark.

Sources: nyidanmark.dk (Danish Immigration Service), the Danish national police force, Statistics Denmark, the Danish Refugee Appeals Board