Alone in a strange country – unaccompanied refugee children

An increasing part of the asylum seekers coming to Denmark are "unaccompanied minors". They are under 18 years and arrive without their parents or other guardians

Among professionals they are called UMIs, and this article uses the word "minors" in stead of children or young people. A 12-year-old from Syria is definitely a child, but a 17-year-old from Afghanistan would probably be considered a young man, also by himself. According to Danish law a person is normally considered a child until the age of 18, but the Alien Act (immigration and asylum law) also uses age limits of 15 and 16 in relation to family reunification.

How many are coming, and who are they?

Most unaccompanied minors are in their late teenage years, and almost all of them are boys. Most often they come from the same countries as the adult asylum seekers; meaning that when many adults are coming from Syria, many unaccompanied minors are also coming from there – however, over the years there has been a predominance of Afghans, especially from the ethnic minority Hazara.

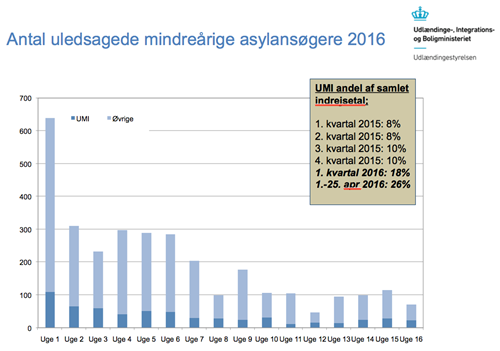

During the first four months of 2016, 629 unaccompanied minors came to Denmark. In April they made up all of 26% of the new arrivals – bearing in mind that the total number for that period was very low. So far this year, the vast majority have been from Afghanistan.

Number of applicants January-April 2016 (in Danish)

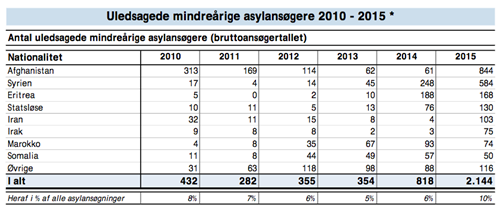

Last year 2,144 UMIs arrived, and out of these were 844 from Afghanistan, 584 from Syria and 168 from Eritrea. In 2014 the total number was 818, and the previous years came around 300 a year.

See chart: Numbers 2013-2016, Nationality + numbers 2011-2016 (in Danish)

If we look at the development from 2014 till today, both the number and the share of unaccompanied have risen rapidly: In the month of January 2016 came almost 300, which is ten times as much as the number for January 2014. Also the share of UMIs out of the total number of asylum seekers has increased. Between 2010 and 2015 the share was 6-10%, and first quarter of 2016 it was up to 18%.

Number of applicants and nationality 2010-2015 (in Danish)

In 2015, 77% of the unaccompanied minors were over 15 years, and 17% were 12-14 years old. Seven out of ten are boys, but the predominance of boys decrease somewhat among the youngest ones.

See chart: Distribution by age and gender, 2014-2015 (in Danish)

A relatively new phenomenon is the group of unaccompanied minors with "street behaviour", mainly from Morocco. They have a very problematic attitude including violence and threats, and often disappear after a few months. The children's centers have difficulties handling them, forcing the authorities to reserve one center only for them, and to make a special compartment in center Sandholm for them. Danish Red Cross held a conference about this group in 2014, read more here (report in Danish).

Traditionally Sweden has received many more UMIs than Denmark, and last year the number rose significantly. From September 22 till November 22 the small municipality Trelleborg in region Skåne with only 43,000 inhabitants had to find accommodation for 4,200 unaccompanied minors – in one day arrived 218. In Sweden, the Afghan boys between 16 and 18 are the majority, as in Denmark.

Why is the number rising now?

The general situation in Afghanistan is deteriorating day by day. Taleban is gaining terrain, and they are always looking to recruit big boys as suicide bombers and to place roadside bombs. The future seems completely hopeless for the young ones and their parents after 35 years of war, and life in Iran as illegal aliens is the only alternative for many. Therefore they risk everything and head for the west – looking for safety as well as a future of education and income.

For the Syrians it is a desperate way to get a whole family to safety – by sending one child out with an uncle, the rest of the family may later get a visa and avoid the deadly, insecure and expensive way with the smugglers. The more Europe closes its borders and makes access to family reunification harder, the more children and teenagers will be forced to flee on their own.

The young ones from Eritrea are hurrying out of the country before they are called in for the harsh military training, which will lead to an indefinite amount of years in the national service program under slave-like conditions. Often the whole family is in debt after paying the smugglers for bringing the child to Europe.

Special advantages

The minors are accommodated in special centers; there are currently 16 of those in Denmark. They get a personal representative through Danish Red Cross, who will accompany them at interviews and meetings with the authorities, and will also act as a social contact and support. However, there is a shortage of representatives in all the centers at this time (see a list of the centers here). The processing of the asylum case is usually faster than the adult ones, but not always.

The children's centers are smaller and much more homely than the normal centers; there is staff around the clock, and a lot of activities are going on. The minors go to school every day (special asylum schools). They are driven or accompanied by an adult if they must go to a meeting, to the doctor etc. To some of the minors it can actually be a disappointment to be granted asylum and be sent out to a municipality where they are suddenly left much more to themselves. However, they still get much more help than an adult refugee gets.

A clear advantage for the unaccompanied is the fact that they will not be transferred according to the Dublin convention because of fingerprints, which means that they can in effect choose which country to seek asylum in.

The chance of getting residence permit

Basically, the minors must meet the same demands as the adults to get asylum, but they often have the impression that it will be easier. Almost all unaccompanied minors go through the normal asylum procedure, as the authorities find them mature enough for that. However, there is no professional assessment of the maturity, and there are examples of reports from psychologists/ psychiatrists who have found the minor not to be mature enough for this procedure – but then it was too late. The only support for the minor is the representative who rarely has any kind of legal training and has no saying in the matter.

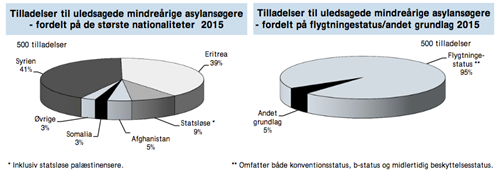

As almost all the minors go through the normal procedure, the decisions follow the pattern of the adult ones: Eritreans and Syrians will all get asylum, whereas more than half of the Afghans will get a rejection. In practice, the authorities will wait until the rejected minors turn 18 to send them back. In 2015, 500 minors were granted asylum and 71 rejected. The high number of permissions reflect that more than 80% of the applicants were from Syria, Eritrea or stateless. Only 5% of the permits were given to Afghans.

Permits, nationality and status 2015 (in danish)

The unaccompanied minors have an extra chance of getting residence permit after another clause in the law (§9c 3,2), but this will not be tried until a final negative decision may be given. This clause can lead to a 1-year residence permit, if the authorities believe that the minor will in fact be all alone without any network in the home country. Very few persons are granted this every year: in 2014 it was 2 persons, in 2015 it was 5 (see link to chart below, in Danish). The authorities may state that the minor has referred to an uncle in the asylum interview, and there is no proof that his mother is in fact deceased (even if the minor does not have any contact with these family members). The permit will expire as soon as the minor turns 18 and will usually not be extended, unless there are special circumstances like very young age at arrival and therefore a strong attachment to Denmark.

"They asked a lot of questions that seemed weird – like trick questions. The same questions put in different ways. During the whole conversation I felt they did not believe me, so it was not a pleasant experience. Also because the translator was from Iraq and sometimes found it hard to understand what I meant." - Milad from Afghanistan

See chart: Permits 2103-2015 (Danish)

Age testing

Very few unaccompanied minors bring any kind of proof of their age, and the authorities judges some of them to be older than they claim. In that case, they are called in for an age test, where a doctor will look at X-rays of teeth and hand bones as well as physical appearance overall – undressed. However, the test does not give a precise result. It was developed in the 1950s in England, and critics claim that it is not useful to determine the age of young people from other parts of the world. Eg. Afghan and Iranian boys can grow a thick beard far earlier than European boys, and teeth and bones can be affected by nutrition and hard physical labour.

In 2015, 351 of the 844 unaccompanied minors were called in for age testing, and 66% of them were found to be over 18 years.

Family reunification

Before 2014 there were only a few applications for family reunification from unaccompanied minors every year. The number has increased with the Syrian UMIs: out of the 657 minors who were granted asylum from January 2011 to August 2015, 185 applied for family reunification, and 128 of these were in 2015.

Almost all the Afghan boys are saying that their family has been killed or that they lost contact with them. This is not always true, as they know they will have a second chance if they have no family (though very small, as mentioned above). Some of the Afghans have grown up in Iran or Pakistan, where their parents may still be living as illegal migrants. The boys do not imagine a reunification and prepare themselves for a life alone – in the hope of being able to send back some money to the family, if they have one.

The situation is quite different for the Syrian minors who keep a close contact with parents and siblings, and they usually have a set plan to apply for family reunification and be reunited as fast as possible. They are often not prepared to handle the waiting period all alone, where asylum processing and family permits can take many months or even years. A 7-year-old girl from Syria had to wait for more than a year to get a family reunification permit for her parents.

The young ones from Eritrea have a third situation: they are in contact with their family, but they don't really believe that the rest of the family will succeed in leaving the home country illegally, which is the only way, so they brace themselves to be alone, sometimes with support from uncles or aunts in Europe.

"When you are alone, you are more responsible, you have to deal with everything yourself, and you don't know if it's right or wrong. I have this feeling that I'm not really safe when my parents are not there." - Zakir from Afghanistan

Unaccompanied minors with asylum on §7(3)

UMIs have the right to apply for family reunification for their parents and siblings under 18 immediately, no matter which kind of asylum status they get – the 3-years waiting period for refugees with asylum on §7(3) does not apply for them. UMIs from Syria almost always get §7(3)-status.

But even if you have the right to apply to bring your parents and siblings here, you may not get the permit. The case processing time is the same as for the adult refugees, which means that you may easily have to wait more than one year in total to see your parents again.

The assessment depends on the age of the minor, both at the time of arrival and the time of the decision. Roughly speaking, the chances will decrease when you turn 15. It is also crucial whether the minor already has one or more persons in Denmark who can form a sufficient family network – eg. the uncle he came to Denmark with, a grandmother or an older sibling.

In the spring of 2016, there has been made 11 decisions concerning unaccompanied minors with asylum on §7(3) who applied for family reunification for their parents and siblings. 4 permits and 7 rejections were given. All the applicants above 14 years got rejections, except a 17-year-old, who had special problems.

Legal guardian

If the minor is granted asylum, the municipality (kommune) has to provide a temporary holder of custody (MFI) who will also be a legal guardian, and in some cases the representative from the asylum phase can continue in this role. It is important for the minor to have a steady, personal relation to an adult who is independent and who will look at the best interest of the minor. If the minor is placed in foster care, this person has a more formal role, as the foster family will take care of the minor's social needs.

In some cases, an older sibling or an aunt/uncle can be appointed as legal guardian in Denmark, if both parts agree to this. The minor and the older family member may even have made the journey to Europe together, and they may have a wish to stay together. Usually this works out fine and is in the best interest of the child – other times it can be an unfortunate decision from the authorities' side. An extreme example was the two Afghan brothers Vahid and Abolfazl, where the older brother was made a guardian for his 16-year-old brother, in spite of the fact that they both suffered from mental problems (anxiety and suicide thoughts). They were deported to Kabul after 5 years stay in Denmark, and it ended very badly: the youngest died and the oldest is now living under ground in Iran. Danish Radio/television made a program about the brothers earlier this year.

Even though many of the UMIs seem mature and independent after the hard life they have had, they are still children – separated from their close family against their will, and much too young to be alone in a strange country. Even the best foster family can't make up for their own family and their home country. On top of this, they are all affected more or less by the cruel experiences they all had in the home country and on the long journey, making them mentally vulnerable.

Residence permit – what happens then?

The unaccompanied minors are placed by Immigration Service in a municipality in the same way as the adults, but a handful of municipalities have decided to make a special effort in this field, among them are Roskilde and Frederiksberg. Consequently they receive more UMIs than others. The reception is coordinated by the child- and youth department and the integration department of the municipality, with responsibility for accommodation, school, health and guardian.

The youngest ones will most often start in a reception class in a local public school, the older ones in a class for foreigners in a youth school, and later they may continue to VUC (adult education schools). Some municipalities offer a stay at "efterskole" or "højskole", which has shown good results. The municipality can choose to extend the extra support for the minor some time after he/she turns 18 if there is a need for this.

A Swedish report has found that a larger part of the UMIs become self-supporting when they grow up, compared to refugee children who arrive with their parents. According to the researchers behind the report this may be due to the UMIs being more independent, having a better network (municipality/ foster family/ representative) and being very concerned with sending money home.

Institution, shared housing or foster family?

Shortly after the minor has been granted asylum, the municipality must have a meeting with him/her in the asylum center, where the issue of accommodation should be discussed. The minors under 16-17 years of age may be offered a foster family, but the most common solution is an institution or a shared housing for young people. In practice, UMIs fall under the same legislation in Denmark as Danish children who are placed in care. Most municipalities don't have a sufficient amount of UMIs to have special houses for them, and therefore they sometimes end up in the same places as Danish children in care. This is not a good idea, as these Danish children have a very different kind of problems than the refugee children.

In an institution there is professional staff (pedagogues) around the clock. A pedagogue in a former orphanage, now housing 20 UMIs from Eritrea, Syria and Afghanistan, tells that they are between 2 and 4 persons on duty all the time. There is also a kitchen lady, preparing the food for the minors. The staff will wake up the minors in the morning and send them to school, and social activities and practical help is offered during the day and in the evenings.

Shared housing is more independent, and some of them are run by Danish Refugee Council's Integrationsnet. Here, a smaller group of the UMIs live together, and a pedagogue/ social worker comes by every day. The young ones will have to do their own cooking and cleaning. This model is used mainly for the UMIs who are close to turning 18.

A foster family can be either full time, meaning that the child lives with the family, or as a support family during weekends and vacations for a child staying in an institution. The foster family must be approved first and will receive an economic support according to the task, as well as compensation for food and lodging. All unaccompanied minors receive the same amount to cover clothes and shoes and some pocket money.

Obviously, foster families can offer the strongest personal care and most effective integration. It is also by far the cheapest solution for the municipality. But many of the young ones over 16-17 years will find it difficult to be "a child in a family". For the ones who are traumatized or have special problems it may also be too much of a task for a family to handle cultural differences and language problems as well as psychological problems. However, many municipalities wish to use this option more and are advertising for new foster families.

Danish friends are hard to find

The 16-18 year-olds can easily be isolated in the Danish system. They don't have time to learn sufficient Danish language to be able to follow a normal public school 8th or 9th grade, and in the youth schools or reception classes they will have no Danish classmates.

Naturally, they will stick to their countrymen when they can, rather than building relationships with UMIs from other countries, but many of them wish to have more contact with young Danes.

Some have the courage to join a local sports club, but it may prove hard to be the only refugee among Danish teenagers. A stay in "efterskole" or "højskole" is therefore more a effective way to access a community of young Danes and will often result in friends for life.

Do you want to do something?

Read more here (in Danish) about becoming a representative, temporary holder of custody or foster family. The two first ones are carried out voluntarily and unpaid, whereas foster families receive some level of economic support. Usually there is a need for all three tasks, depending on where in Denmark you live. If you are young yourself, you can join Danish Refugee Council's youth network DFUNK, offering a lot of young-to-young activities.

More about UMIs:

• Award winning documentary by Michael Graversen: "Drømmen om Danmark" (Filmstriben)

• DR2 (Danish TV) has shown three documentaries about refugee children, unfortunately no longer online.

• Brochure from Børnerådet: "Man har brug for både held og hjælp" (in Danish)

• Homepage of Immigration Service (in English).

All numbers, charts and tables are taken directly from Immigration Service.

Photos by the author + DFUNK. Quotes are taken from Børnerådets brochure.