Interpretation in asylum cases 1:2 / Facts concerning legislation and standards

The National Audit Office has documented that the use of interpretation services by the authorities is haphazard and represents a serious risk for incorrect decision-making – it is far too easy to become an interpreter

In this article, we present the facts concerning how interpreters are used within the asylum system. In our second article, ‘Practical experiences and examples’ you can read interviews with an interpreter and a case worker and see RW’s recommendations.

The National Audit Office has, on its own initiative, investigated the use of foreign language interpreters within the areas of law, asylum and health, and in March they published a 50 page account, ‘Myndighedernes brug af tolkeydelser’. The conclusion was clear: the standard is by no means satisfactory and it has a negative effect on both legal decisions and patient safety. The National Audit Office recommends that a common upgrading of interpreters abilities should be established and they refer to the positive experiences from Norway. RW have for many years been critical of this area, including in an editorial from 2012 ‘Dødsensfarlig tolkning’ and welcome the report from the National Audit Office.

Refugees are also over-represented when it comes to dependence on interpreters in the health system and in dealings with local municipalities, where the interpreters’ skill levels are often even lower. Our article primarily focuses on the processing of asylum cases.

Why are interpreters so important in asylum cases?

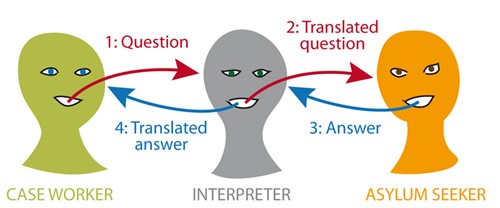

As a rule, asylum seekers rarely speak Danish and even though some speak English or French, all conversations with the authorities must go through an interpreter, as case workers don’t necessarily speak anything other than Danish. The written application form for asylum is 7 pages long and must be filled out in the applicant’s mother tongue and then translated on paper. Asylum interviews at the Immigration Service – there are normally two of these – last between 3 and 7 hours and a summary is written in Danish during the course of the interview. This summary in Danish is then translated orally for the applicant at the end of the interview.

A possible meeting with the Refugee Appeals Board as well as the introductory meeting with a lawyer both take at least 2 hours and here a short summary is also written in Danish. All of these many hours of communication between asylum seekers and the authorities are conducted via different interpreters who are chosen from the Danish National Police’s list of interpreters.

Both questions and answers are reliant upon how the interpreter perceives and translates what is being said.

It’s not just a question of getting an idea or a message through to the other party. A large part of an asylum case (often the most important part) consists of the evaluation of both the applicant’s credibility and exactly how great a risk they are exposed to. Here, emphasis is placed on details in the description of situations, the person’s manner and precise expressions. Even the language or the dialect the applicant speaks is assessed in terms of the credibility of their identity. If an applicant asks to make amendments to the summary or if the same question is answered in a slightly different way in the different summaries, this is often perceived as ‘divergent or enhancing explanations’ and can lead to the rejection of an application.

When all of this has to go through an interpreter, who doesn’t necessarily write/speak both languages to a sufficiently high standard, and who doesn’t always work professionally in relation to the ethical rules of interpretation, there is a great risk that the result will be inadequate or misleading. Incorrect decisions can be made, and this can put the lives of asylum seekers on the line.

Many rejected asylum seekers blame interpreters for not understanding them and see them as being the cause of their rejection. It is a minority of cases where you can say that the interpreter alone is to blame, but it can’t be denied that it plays a role, to a lesser or greater extent, in many cases. The National Audit Office found that one quarter of case workers in the Immigration Service ‘often’ experience uncertainty in the details concerning cases, as a result of bad or inadequate interpretation. It’s a fact that many mistakes and misunderstandings can occur when interpreting and that these could be greatly minimised by introducing serious quality-control within the branch.

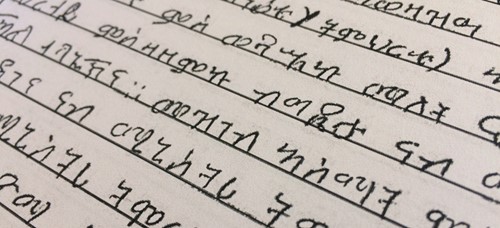

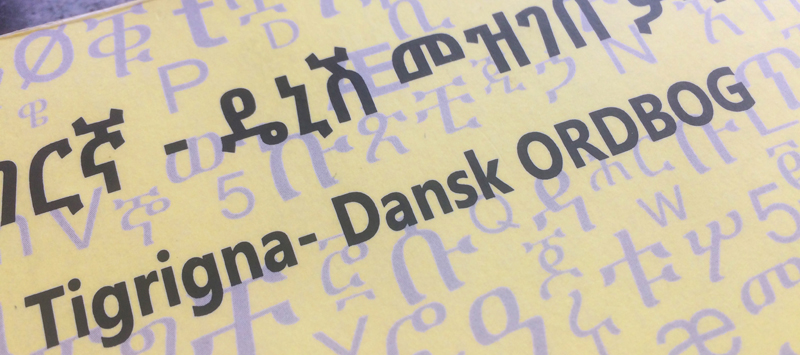

Hand-writing from an asylum application, Tigrigna

Who can be an interpreter?

In Denmark, there is essentially no requirement for qualifications in order to be an interpreter, making it the only profession in Denmark which is entirely without the requirement for documented competence. The Immigration Service and the Refugee Appeals Board only use interpreters who have been included on the Danish National Police’s list. However, it is alarmingly easy to be added to this list. In 2017, 1,832 interpreters were on the list, covering 137 languages and dialects. The list is not publicly available. The interpreters either work as self-employed or through interpretation bureaus, and under the Ministry for Justice the hourly rate lies between 328 – 573 DKK, depending on the interpreters category. For local municipalities and municipalities, interpreters work for hourly rates of as little as 200 DKK and here there is no requirement that they be present on the National Police’s list.

In 2015, the National Police published ‘The Interpreter’s Handbook’, which includes 9 pages with relevant and important information on working as an interpreter – and 21 pages about sending invoices. The handbook also presents a brief overview of what is expected of an interpreter in connection with various different tasks, e.g. that when in court, the interpreter must be able to differentiate between terms such as ‘separation’ and ‘divorce’ and that when working for the Immigration Service, they must have familiarity with precise terms concerning weapons and the military. However, there is absolutely no information about where you can acquire this knowledge – and nobody checks whether or not you have it.

As a result of Denmark’s EU opt-out, we are not required to adhere to the EU’s requirements in this area – and even if we were, we couldn’t live up to them.

The Immigration Service has chosen to make their own database of interpreters, which includes information about the interpreters backgrounds and experience and which includes fewer interpreters than the Police’s list. According to lawyers and interpreters we have spoken with, in practice the Refugee Appeals Board works with an even smaller group of interpreters and they place higher demands in terms of their abilities than other authorities.

All asylum interviews take place at the asylum centre in Sandholm

“Mother tongue interpreter”

If you can speak and write relatively fluent Danish and have another mother-tongue, you can be approved to interpret between the two languages. This is called mother-tongue interpretation and 77% of all interpreters on the National Police list belong to this category. You can be accepted onto the list by filling out a questionnaire and taking part in an interview at your local police station, but the procedure varies from place to place. The National Audit Office’s spot-check showed that the limited information which is required isn’t even collected in all cases.

The Police have no chance to assess the standard of the applicant’s abilities in languages such as Somali, Kurmanji or Tamil and the use of control-translations has proved to be sporadic and limited to certain languages – many are not even tested in their ability to translate to Danish. In addition, you also have to complete a 1 day course on interpretation techniques, ethics and invoicing.

The future interpreter has perhaps never received teaching in their mother tongue – rather they have just spoken it with their family at a non-complex level, often with a limited vocabulary and incorrect grammar. There are also 112 interpreters who are approved to interpret in 4 or more languages – which means that it is not only their mother-tongue they are working with.

Interpreters with another form of education

Other categories of interpreter are state authorised translators (8%), state-assessed interpreters (2%) and interpreters with a higher education in a second language (13%). These interpreters typically have a higher hourly rate of pay. However, ‘state-assessed interpreters’ no longer exist and the title of translator is not acquired through an education but rather an exam, which very few take. At Aarhus University, the M.A. in International Business Communication can be taken in English, Spanish, German and French. For the majority of the languages that are most in demand (such as Somali, Pashto, Urdu, Farsi, Tamil and Tigrigna) there is no official education or certification.

A number of private companies offer courses and educations (tolkeuddannelsen.dk and Tolkeakademiet) but these are not recognised educations. The website ”Det Nationale Tolkeregister” was set up by a private interpretation firm. The Army’s education as Language Officer – a two-year-long course, which also includes military training and deployment with the army – can only be done in Russian, Arabic and Dari.

Receipt from Sri Lanka, Singalese

Complaints about interpreters

The National Audit Office points out that there is inadequate inspection of interpreters and that problems go unreported. Only the local authorities – those who in fact ordered the interpreter’s services – have the right to complain, and not those who have been interpreted. Nonetheless, when asked, one in four of those working for the authorities who were involved in the study answered that they had complained about interpreters. Case workers can complain within the Immigration Service’s own database but this complaint is not registered anywhere else.

Asylum seekers are not informed that they can complain about interpreters or that they can stop the interview if they aren’t satisfied with the interpreter. By way of introduction, case workers from the Immigration Service ask if the interpreter and asylum seeker understand each other – via the interpreter! It’s difficult to say no, and there are many other factors which also mean that asylum seekers will endeavour to complete the interview, even with the most hopeless interpreter. Applicants have often waited for that day for many months, are nervous and are looking forward to getting it over with. Calling it off would mean new waiting time and irritation from both the Immigration Service and the interpreter. You try to make a good impression as you think that a difficult complainer will have a worse chance of getting asylum.

Finally, there can also be other things than just matters of language that can make applicants feel insecure with interpreters, and which can be difficult to explain via the interpreter themselves. For example, the interpreter may have expressed some personal opinions, threatened or dismissed something. If the applicant becomes nervous that the interpreter might give details concerning them to others in their homeland, or if they express their own opinion concerning the applicant’s case, the applicant will react by withholding important details in their case and in doing so, can ruin their own chances. See examples of this in our second article.

The health clinic at Sandholm – for some inexplicable reason, the information is presented in Danish and German.

The interpreter and the authorities are colleagues of a sort and have often worked together previously. This connection can often be noticed by the applicant and it creates an even greater fear of complaining. The interpreter will naturally also attempt to quash any sign of dissatisfaction.

There is also an additional false insurance built into Immigration Service procedure. Applicants are asked to sign each individual page of the interview summary after it has been translated orally by the interpreter. But this is not a guarantee against misunderstandings as the same mistake can easily be repeated unnoticed at this stage – and the interpreter can skip a paragraph without anyone being able to check it. This also often takes place late in the day, when everyone is tired and just wants things to reach a swift conclusion.

See examples in our second interpreter article.

If an audio recording of the interview existed, with the help of another interpreter, a lawyer would be able to clear up potential misunderstandings or unethical behaviour before the case was brought to the Refugee Appeals Board. Both RW and Foreningen af Udlændingeretsadvokater (Association of Immigration Rights Lawyers) have recommended this for many years. In place of this, the applicant can record the interview on their own smartphone – a practice which is allowed.

Ticket from Egypt, Arabic

Children as interpreters

According to law, children over the age of 15 can be used as interpreters within health services in special situations. Children are never used as interpreters in the processing of actual asylum cases but at asylum centres and in connection with meetings with local municipalities, lawyers, journalists etc., it is often the eldest child in the family who ends up acting as interpreter. This is a huge problem from an ethical perspective, firstly, because children are exposed to things they perhaps shouldn’t have to know and secondly because they can become extremely stressed by the weight of the responsibility they bear for correctly understanding and translating important interviews. Everyone involved with asylum seekers and refugees should be aware of the importance of not using children as interpreters – even though it can often seem like the easiest option. Legislation should also be tightened so that the practice is avoided in all contexts.

Challenges with certification and requirements

The establishment of a state-recognised interpreter education supported by the state education grant, examination and certification of experienced interpreters at different levels, courses in subject-specific terminology, publicly available lists of interpreters and their abilities, and a gradually introduced requirement that the authorities may only use interpreters with the necessary approval are all examples of practices that would ensure a much higher skill/accuracy level and greatly reduce the risks for making mistakes.

However, there will still be problems, even in the most idealised system. Interpretation is difficult by nature as the three people involved can perceive and express themselves in different ways, depending on their background, culture, opinions, experiences etc. The interpreter should be a neutral filter, which formulates and transmits the message perfectly – but this cannot happen. Therefore, specific sentences and answers within an asylum case should not be given as much significance as they are given today.

Supply and demand will also create problems, even if the recommendations listed above were to be implemented – perhaps they would even make it worse. The languages spoken by newly-arrived refugees change rapidly. For example, for many years just a few hundred asylum seekers came to Denmark from Eritrea each year but in 2014, over 2,000 came in the space of just a few months. The few Tigrigna interpreters operating within the system simply couldn’t meet the demand and Immigration Service was forced to advertise for more. Afterwards, it was discovered that some of the old interpreters sympathized with the regime in Eritrea and you could therefore not be sure that they hadn’t passed on detailed information concerning the new applicants.

Tigrigna-Danish dictionary, which an interpreter has produced as no official dictionary between the two languages exists

Some languages are so uncommon that it would be difficult to educate and examine interpreters – even now, there are not interpreters for every language. Here, it could be possible to enter into a co-operation between the Scandinavian countries or to make more use of the applicant’s second language rather than their mother-tongue.

Today, one of the requirements from the National Police is that the interpreter must not have “connection to foreign authorities”. However, in the National Audit Office’s spot-check many had been approved without all of the requirements being checked. And how can such a thing be checked in a reliable way? There are many situations where the interpreter comes from the same country as the applicant and perhaps from the opposing side in the conflict which led to their applying for asylum. For example, an Assad supporter can end up interpreting for a supporter of the rebel forces. Even if the interpreter endeavours to behave professionally, it will still have some sort of impact on the case.

This problem could be resolved by choosing an interpreter who spoke the same language but came from another place – something asylum seekers themselves favour. For example, an Iraqi interpreter could translate for a Syrian and an Afghan for an Iranian. However, there are many differences between dialects and the same expression can mean different things in Morocco and Lebanon, metaphors can be utterly unknown for one of the party, town names can be spelled incorrectly etc.

Experiences from Norway and Sweden

Sweden has, for many years, had state authorization of interpreters and they also have a state register of authorized interpreters working in 45 languages. They also educate interpreters within specific fields of expertise. The demand for certain languages has at times been greater than the register could meet and therefore the use of interpreters without authorization is allowed for certain tasks.

Norway had the same problems as Denmark but decided to do something to increase the quality. In 2005, a publicly available, national register of interpreters was introduced, with 1,800 approved interpreters in 66 languages. The interpreters are divided into 5 categories, where the minimum requirement is the completion of a three-day course in ethics and techniques as well as a test in both Norwegian and the second language. An internet-based and part-time education as an interpreter, divided into two modules is also on offer, after which you can take a part-time bachelor degree over 4 years. In order to achieve state authorization, you have to pass a practical interpretation test and so far, this can be taken in 29 languages. During 2018, it is expected that the Norwegian parliament will pass legislation with a set of requirements for when authorities must use interpreters of a specific standard.