Refugees from Eritrea are a fantastic success in the Danish labor market

Employment figures for the refugees who arrived five years ago are both surprising and positive

The picture above was taken in a summerhouse July 2015, shortly after the four Eritreans had received their residence permits. None of them have been relying on social benefits except for the first months. Today they are respectively: glazier apprentice after finishing 9th grade and FVU in Danish; chauffeur for an embassy; machine carpenter in a furniture factory in spite of university degree from his home country; and working as a consultant for vulnerable families after finishing a university masters degree in Denmark. One has married a Dane, another has been reunified with his Eritrean wife.

During the so-called 'refugee crisis' five years ago, the vast majority of those who came to Europe were from Syria. And the same was true for the 10,000 who were granted asylum in Denmark at the time: more than half were from Syria. There was a big focus on that group, and almost none on the second largest group: those from Eritrea. But how have things gone, here five years later? A new analysis shows that the Eritreans have been incredibly resourceful at gaining employment, with rates equalling those of Danish women – see the statistics later in this article. A fantastic success story, which the Danish Minister of Integration has remained silent about.

A new refugee group in Denmark

In 2015, 2,400 refugees from Eritrea were granted asylum, and some of them got permissions for their families to enter in the following years. In total about 5,000 Eritreans came from 2014-17. They did not get nearly as much attention as the Syrians, and were completely unknown in a Danish context, though not in Europe. There was a bit of talk in the corners that they could become "the new Somalis" – a phrase intended to denote a group that kept to itself, stuck to its home country's traditions, with low levels of education and difficulties in finding jobs. Both countries are located in the Horn of Africa.

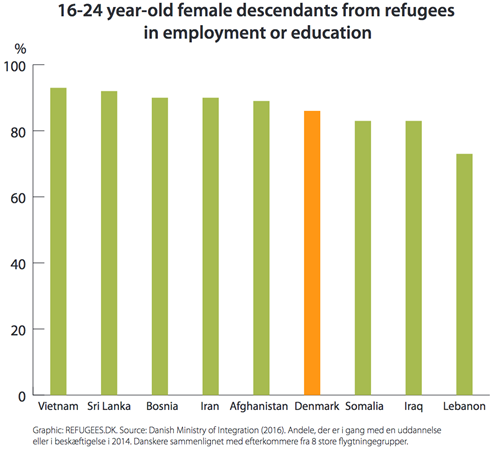

However, the negative image of Somalis is exaggerated. Refugees from Somalia arrived during periods when there was much less focus on helping refugees complete Danish courses and get a job, and they still are met with great distrust in the labor market. Somali women, on the other hand, have gotten more jobs than Lebanese and Syrian women, and the next generation has been adept at breaking their social heritage; many young Somalis have come to university despite having an illiterate mother.

Additionally, the statistics relating to Eritreans show a starkly contrasting and very surprising picture – never has a refugee group become self-sufficient so quickly and to such a great extent! There are many factors other than education that are crucial to getting a job.

Traditional Eritrean food: injera.

From a different world

Both Syria and Eritrea are dictatorships, and many refugees are traumatized to varying degrees. The Syrians come from a devastating and bloody war that struck them quite suddenly. The Eritreans come from a more stable everyday life, where many in turn have lived in miserable conditions, been imprisoned and have performed forced labor for years. The Eritreans have been subjected to far worse abuses and greater risks on the long journey through Libya and across the Mediterranean than the Syrians, who have typically traveled via Turkey.

Eritrea is one of the poorest, most closed and least-developed countries in the world. It is led by a cynical dictator who exposes the population to incredible suffering. There is no internet access outside the capital, and the country's only university was closed in 2003. It uses the Amharic alphabet, which is fundamentally different from ours, and very few speak English. Against this background, it might seem impossible to enter the Danish labor market. But there are a number of other factors that have helped them.

Demonstration December 2014: All Eritrean asylum cases were put on hold while Immigration Service made a country report which turned out to be biased and not usable.

The social profile of Eritreans

Almost all Eritreans who have come to Denmark belong to the Christian part of the population. They are however orthodox and have their own churches and rituals, which are far from those of the Danish national church – but many Danish congregations do a lot of integration work, and they have been good at inviting the Eritreans into their local communities.

Eritreans drink beer and go to bars, which can also make it easier to make Danish friends and become part of the social environment in the workplace. The women dress in western clothes, and some have even served in the military. The Eritreans are known as polite, kind, calm, reliable, conscientious and very hardworking. Slightly reserved, suiting the Scandinavian temperament. The Eritreans also have a form of humor that is close to the Danish – using irony, making fun of each other and not being easily offended.

Danish workplaces that have employed Eritreans, for example in IGU courses, say quite unanimously that their language skills and training have often been a challenge, but that their discipline, reliability and social skills have fully offset these. The vast majority of Eritreans have been employed in service, warehousing, retail, transportation, cleaning and agriculture.

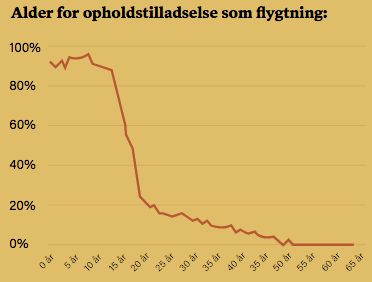

Finally, the Eritreans in Denmark are very young – a large proportion were teenagers or in their twenties when they arrived. Many have brought their wives and children up here subsequently, predominantly smaller children and women in their twenties and thirties. Many of the Syrian refugees are older, which generally makes it harder for them to learn the language and get hired. In both groups, most of the refugees are men.

Eritreans dipping into the cold, Danish sea in Januray 2015, celebrating an Orthodox Christian holiday.

Eritreans surpassed Syrians in levels of employment

Five years ago, the Danish media and politicians were very concerned about whether it would be easy or difficult to introduce Syrian refugees into the Danish labor market. Would cultural differences and lack of education drive them to welfare? Or were there many highly educated people among the Syrians as Akademikerbladet wrote in 2016?

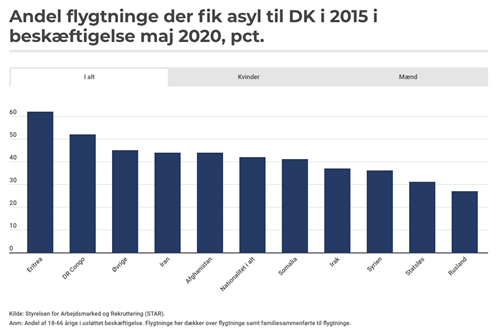

The new Danish Knowledge Center for Integration has looked at how many of the refugees who were granted asylum in 2015 are in unsubsidized jobs five years later. The analysis shows that the Syrians have done better than previous cohorts of refugees, with a total work rate of 50% after five years. But other groups have surprisingly fared even better; Afghans, Somalis and Iraqis, who arrived the same year, are employed at higher rates. At the same time, one must remember that the numbers show the average for a large and diverse group. The media have told of many examples of young Syrians of both sexes who have rushed through the school and achieved top marks – in Danish!

But the clear top scorers in the analysis are Eritrean men, who only five years after arrival are employed to almost the same extent as Danish women, namely 71%. Danish women are among the most active in the world (72%). This is very impressive when one considers the starting point. The Congolese are also at the top – especially the women – but the group is very small (a total of 51 people), which means that few people can make a big difference.

Employment January 2020 among refugees granted asylum in Denmark 2015, percentage. Unfortunately all graphics are only in Danish. Danmarks Videnscenter for Integration.

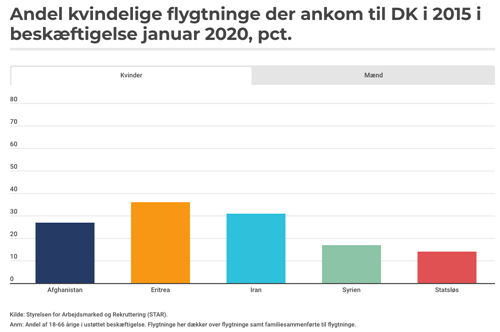

Female refugees are generally far below men in terms of employment. But here, too, the Eritreans do better: the gap between men and women is far smaller among the Eritreans (men 71% / women 33%) than among the Syrians (men 50% / women 14%).

Employment January 2020 among female refugees arriving in Denmark 2015, percentage. Unfortunately all graphics are only in Danish. Danmarks Videnscenter for Integration.

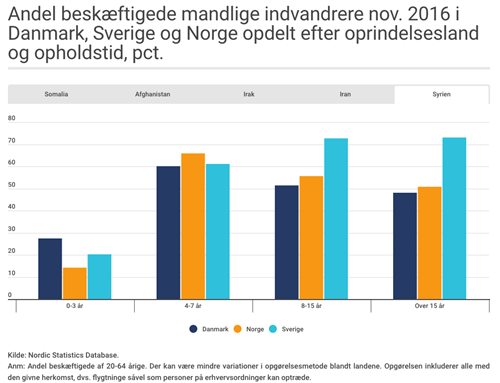

Overall, refugees have done exceptionally well in recent years in gaining employment. But where Denmark has focused unilaterally on finding unskilled jobs for people as soon as possible, Sweden and Norway have focused on teaching the new inhabitants the language and giving them an education first. In the short term, Denmark’s policy gives slightly better numbers for the men, but in the long term, the neighboring countries' strategy gives much better results, especially for women, despite the fact that they have received a larger number of people.

Percentage of male immigrants in employment November 2016 in Denmark, Sweden and Norway by country and length of stay. Unfortunately all graphics are only in Danish. Danmarks Videnscenter for Integration.

Percentage of female immigrants in employment November 2016 in Denmark, Sweden and Norway by country and length of stay. Unfortunately all graphics are only in Danish. Danmarks Videnscenter for Integration.

The significance of education levels

In 2017, the Rockwool Foundation made a large survey of immigrants' level of education from home, which showed that 66% of Syrians have primary school as their highest level of education – constituting the lowest level of education among the large groups of foreigners in Denmark. Only 3% of Syrian refugees comes with a long higher education (compared to 20% of Iranians). Statistics Denmark followed in 2019 with similar results.

Highest education completed among the 6th to 10th largest nationalities of immigrants 25-64 years old, June 30th 2016, percentage. Unfortunately all graphics are only in Danish. Rockwool Fonden.

The average level of education among Eritreans is also low. But enrollment in language schools actually reveals that the Eritreans have higher levels of education than the Syrians. In 2016, there were proportionally more Eritreans in Danish 2 and 3 (which are adapted to students with the middle and highest level of education) than in Danish 1 (adapted to illiterate / short schooling), as compared to Syrians.

However, researchers from KORA reminded us that it is a Danish education that is crucial for one's connection to the labor market, and not a previous education from another country. And very few in the two groups of refugees have been in Denmark long enough to get an education here. Therefore, it is difficult to compare Syrians and Eritreans with groups such as Iranians and Bosnians, most of whom have been here for many years. And therefore it is interesting that the Danish Knowledge Center for Integration has only looked at those who arrived in 2015.

In general, there are major barriers to getting a Danish education among the first generation of refugees. The Danish Students' Union published a shocking study in the spring of 2020, which showed that the chance of getting an education decreases sharply the older a refugee is on arrival. The 0-13-year-olds are in line with Danes, but thereafter rates drop quickly. For those who arrive as young adults, only 19% enter the educational system.

Refugees starting a youth education or higher education by the age they had when they were granted residence permit, 20-65 year old in 2017. Graphic from the analysis "Refugees in education", DSF 2020. Unfortunately the analysis is only in Danish.

In the future, the situation will likely only get worse, because the political focus is solely on getting newcomers into jobs as soon as possible. Since 2015, education has not counted at all toward requirements for permanent residence, which is a huge problem for young refugees – see for example Rahima's and Bhupa'stories here. Second generation, ie. young people who grow up in Denmark whose parents are refugees, on the other hand, enjoy high rates of education. Where first-generation refugee women have a lower education and employment rate than men, second-generation women overtake their brothers.

What can we learn?

It can be concluded that the fear of the relatively large number of refugees who came to Denmark five years ago was excessive. Although many came at once, and from very different cultures, they succeeded more quickly than ever in finding jobs, learning the language, and thriving in their new surroundings. A large part of the success can be attributed to the refugees' own will and energy, but increased focus and a greater effort in the municipalities has also had a very positive effect. It is remarkable that the Danish Minister of Integration has not highlighted the success that lies in these figures.

A successful integration policy requires the continuous collection of experiences and evaluation of previous strategies pursued. Every nationality and every individual has strengths as well as challenges, and the same tools do not work for everyone. It's about time that the government starts recognizing the resources and efforts of the refugees in stead of focusing on returning them. In fact, the Paradigm Shift has already had a negative impact on employment for refugees.

We depend on members

to write articles such as this one!