Refugee fathers become mentally ill while waiting for family reunion

A new Danish study proves the negative consequences when refugee families are waiting to be reunited

FACTS:

The study is based on data from Danish registries between 1995 and 2015, covering a total of 120,000 refugees over those 24 years. This group includes the ones who arrived as asylum seekers as well as the ones who joined later as a result of family reunification. Out of the 33,000 in the group where the father arrived first, 19,000 were children and 6,800 were fathers. The study looked into the mental health of those 6,800 fathers. The authors come from University of Copenhagen and from the Rockwool Foundation Research Unit which financed the study. Download the full study here (in English).

Family reunification cases concerning refugees:

2020: Applications for partners and children in total: 1,467 (whereof 910 permits).

Eritrea: 256 applications for partner (149 rejections, 107 permits) = 41,7% chance

Syria: 209 applications for partner (93 rejection, 116 permits) = 55,5% chance

Afghanistan: 134 applications for partner (54 rejection, 80 permits) = 59,7% chance

Photo: 7-year old girl celebrates her birthday with her father for the first time ever, shortly after arriving in Denmark with her mother. Private photo.

The new study

Danish researchers present a study which is the first of its kind in the world. The study documents how the waiting time affects refugees in Denmark who are waiting for their families to arrive – most often fathers who have been forced to leave wives and children behind in the home country or in a third country.

The findings are significant. The risk of getting a psychiatric diagnosis is twice as high for refugee fathers who are waiting for their families to arrive than among other refugee fathers – and the risk increases with longer family separation. More than 20% of the waiting fathers have been diagnosed with a mental disorder, the most common one being PTSD.

According to the research group, countries receiving refugees should be aware that delaying family reunification can lead to adverse mental health effects. Poor mental health can spill over into worsened labour market attachment, making family poverty more likely. On a long-term perspective, parental mental health problems are found to be associated with increased risk of mental health problems and lower school performance among refugee children. Such potential costs should be considered when implementing policies prolonging family separation periods.

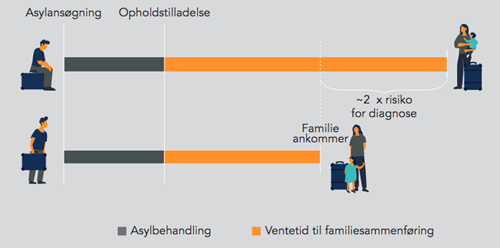

Illustration from Rockwool Foundation Research Unit

Why are refugees separated in the first place?

The majority of asylum seekers arriving in Denmark were already part of a nuclear family before being granted asylum. However, most families arrive separately, and most often the men arrive first. This is sometimes misunderstood as if the men did not care about their wives and children, but in fact it is a choice they are forced to make in order to secure their families in the best way.

Firstly, the strongest motive for asylum usually lies with the husband or the young son in a family – for instance, political activities or refusing to perform military service. This means that the men are in more immediate danger than the other family members, and for the same reason they also have a better chance of being granted asylum.

Secondly, the journey from their home countries to safe host countries such as Denmark is long, dangerous and expensive. No man wants to risk the lives of his children and maybe pregnant wife on a journey like that if it can be avoided. But very few imagine that the separation will last for 4-5 years.

Phases of the waiting time

The fathers do not know how long it will take to process their applications, first for asylum and then for family reunification, neither the outcome of the applications. Hence, they wait with ‘double uncertainty’, which can increase the risk of mental disorders according to the new research study.

Eight out of 10 of the fathers in the study have waited for more than a year to be reunited with their families, and one out of four have waited more than two years.

Several long periods can separate a refugee family. The first one is often the flight itself, which can take many months or even years, before reaching a safe country and applying for asylum. Then there is waiting time while the asylum case is pending, which can easily take one year – and if granted, a new case handling time for the family application, most often also around one year. If that one is rejected, the appeal case can last 2 years at the moment in the Danish administration – and might end up in the court system, or the case can be re-opened and start all over.

Recently Denmark was convicted of violating refugees' right to family life in the case M.A. v. Denmark at the Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. The issue in that case was an extra waiting time (or quarantine period) of 3 years applied to a group of Syrian refugees on purpose by the Danish parliament. However, this does not concern the families in the study, as the mandatory waiting period was introduced by law in 2015, when the study ends

Omar was one of the fathers who was told to wait 3 extra years for his wife and children: "My family and I have been separated for four years, as they had to stay behind in Syria. It gave me a severe depression, as my family was in great danger and I was not able to support or help them. Our youngest child was six years old at that time, and he suffered from mental problems because of the war. He is now 12 years old, and still has fears, anxiety and difficulties with adjusting to his new life here. We are grateful for everything Denmark has given us, but nothing can compensate for the mental pain we suffered through four years of separation."

Omar with his family in Syria before he had to flee with his eldest son

Worst cases are not covered by the study

The new study does unfortunately not show anything about the ones who fail in the system: fathers who apply and appeal in vain for years, due to the very strict rules and demands on documentation which refugees are not always able to live up to. In 2020, 58% of family applications for a partner from Eritrean refugees in Denmark were turned down, among other reasons because their marriage certificates are not accepted, and cohabitation cannot be proven.

Those fathers will appear in the data set as "single", though they are in fact not. And they are probably the ones most severely affected of all. According to our experience with this kind of cases in Refugees Welcome, those are the ones most severely affected. The authors emphasize that there is an urgent need to explore the mental health consequences for refugee fathers who are denied family reunification.

An example of such a case is Misghinna who arrived from Eritrea and was granted asylum in 2015. He had to leave his young wife behind in Eritrea before crossing the desert and the sea to Europe. His application for family reunification was turned down. The couple had lost their first child but had another one in 2018 as a result of his visits to her in Ethiopia, where she is staying. Their appeal case is still pending, leading to 6 years of separation. Misghinna is close to a mental breakdown but manages to keep his job in order to support himself and his family. Read his full story here.

Misghinna: "I feel Denmark as a kind of brain-prison now. Economically, socially, mentally I have been in prison for the last 6 years. I have trauma and feel anxiety, tired, hopeless... even in the worst dictatorships families are not separated like this. I was planning to continue my studies, but now it's not possible. Even if I have done all I could, and everything is ready for my wife and son, I feel guilty because I still failed. Every day my son says: 'Tomorrow we are going to my dad.' My heart aches."

Misghinna and his wife were engaged in 2012 and married in 2015

Critique from Danish Ombudsman

The Danish Ombudsman has criticized the waiting time in these cases back in November 2020, but the problem keeps getting worse. At the moment, Refugees Welcome is involved in or aware of 6 cases where the total expected waiting time is so far between 18 and 27 months – only for the appeal case at the Immigration Appeals Board. The authorities excuse themselves by being understaffed and the Covid-19 epidemic. Both explanations seem quite weak, as the number of family reunification cases overall has dropped from 18,776 in 2015 to 4.61 in 2020, and none of the cases require personal meetings with the applicants.

As a member you support our efforts

to help refugees being reunited

as fast as possible