New ruling: Denmark violates refugees’ right to family life

The European Court of Human Rights has ruled against the mandatory three years waiting period on family reunification concerning 4,000 Syrian refugees in Denmark

The ruling shows that Denmark has not only “approached the limit” of human rights, as the government is doing deliberately when it comes to deterring refugees, but has overstepped the line. Unfortunately, the damage has already been done for the many who have been separated a long time, had to see their family embark on a dangerous journey, or have travelled back to be reunited with their loved ones.

Omar, who lost his case and had to wait for three years, writes to us today:

“My family and I have been separated for four years, as they had to stay behind in Syria. It gave me a severe depression, as my family was in great danger and I was not able to support or help them. Our youngest child was six years old at that time, and he suffered from mental problems because of the war. He is now 12 years old, and still has fears, anxiety and difficulties with adjusting to his new life here. We are grateful for everything Denmark has given us, but nothing can compensate for the mental pain we suffered through four years of separation.”

Omar is the second person from the right. The picture is from 2016 and shows the four persons who sued the state in 2016.

The process

Six years ago, Denmark introduced as the first country in Europe a special, weaker asylum status for Syrian war refugees, and one of the limitations in rights was a mandatory waiting period of one year, which was soon expanded to three years, before they were even allowed to apply to have their family members join them. Shortly after, other countries in Europe agreed on similar waiting times for refugees’ family reunification.

Back in 2016, Refugees Welcome met with the lawyer Christian Dahlager and a group of Syrian refugees who had been affected by the Danish legislation, to discuss a plan for bringing them to the courts. One of them was Omar, whom we wrote about for the first time in 2016.

Dahlager worked pro bono and took some of the cases to the National Court and later to the Supreme Court, where the Danish state sadly enough got a blue stamp for the law. The judges defended the state’s right to limit a ‘mass influx’ to the country – in spite of the fact that the number of new arrivals had dropped significantly at that time – and found that it was not a hindrance to family life but just a postponement. The family members who lost their cases were deemed to cover the costs for the court.

But one of the cases was taken to the human rights court in Strasbourg and further on to the Grand Chamber, because the court had never previously considered a similar matter, though several other countries had introduced waiting periods for refugees’ family reunification after Denmark had led the way in 2015.

Basically, the court had to assess a fair balance between two opposite interests: the refugee’s right to re-establish a family life in safety, and the state’s right to limit immigration. Important considerations here are whether the resident has strong ties to the host country, whether there are strong family ties and maybe dependence between them, and whether there are serious obstacles for obtaining a family life elsewhere.

The court decision

The new ruling, ”M.A. v. Denmark”, was rendered on July 9th with a dissent from only one of the 18 judges of the Grand Chamber.

The court found that the couple had indeed established a strong family life after 25 years of marriage and two children, and that it would be impossible for them to maintain it in Syria. Even though the judges respected Denmark’s wish to reduce immigration, they found that three years is too long to be separated from your family, especially as these family members found themselves in a very insecure area (Syria), especially because time for the flight, asylum case processing and family reunification process will all serve to further lengthen the waiting period.

According to the judges, the Danish state should have assessed the cases individually, carried out an ongoing assessment of the situation in Syria, and reconsidered the legislation when the number of new asylum seekers in Denmark dropped significantly (shortly after the new law was passed). In total, the court found that the Danish state did not find the right balance between the conflicting interests, and thereby violated article 8 concerning the right to a family life of the European Convention on Human Rights.

But already in 2016, the European Human Rights Commissioner addressed the Danish government and warned against the three-year waiting period. She emphasized that all refugees (regardless of their status) have a right to be reunited with their family, and that this furthermore constitutes a safe and legal way to safety for refugees from Syria. She also argued that family reunification is a prerequisite for successful integration.

UNHCR likewise warned against the waiting period and the serious negative consequences of separating families due to flight. UNHCR agrees with the European human rights commissioner that the right to family life covers all refugees, no matter which status they were granted. The letter also informed the Danish government that refugees with subsidiary protection (in Denmark under section 7(2) and 7(3)) in general are in need of protection for the same length of time as convention refugees (section 7(1)).

Denmark is not under pressure

Unfortunately, the court accepts the discourse of immigration being an economical burden, and that integration will be easier if fewer new people arrive – but both views are questionable. There are analyses showing that immigration adds to the economy of the host country. And family reunification adds to both the will and the ability to integrate. During the periods when Denmark had the highest number of new arrivals (1995 and 2016) integration has been more successful than other periods.

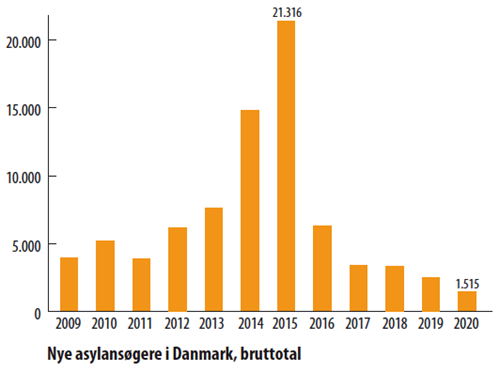

The court in Strasbourg also mentions that in times of high influx numbers a state can choose to grant protection to more people instead of allowing family reunification. But family reunification is in fact the only safe way out of Syria, and Denmark has at no time (except maybe November 2015) been seriously under pressure by the number of new arrivals. Since spring 2016, when Sweden closed its borders, and until today, extremely few asylum seekers have arrived in Denmark. We receive far less than our fair share measured by inhabitants in Europe. The judges could have disagreed with the state’s right to limit the number of refugees when the numbers have been so low.

New asylum applicants in Denmark, gross numbers

Another European court, namely the EU court in Luxembourg, has taken a different position, as it does not find that refugees with subsidiary protection necessarily have the same right to family reunification as convention refugees. And it actually accepted a three-year waiting period in an EU directive from 2006 with the curious argument that integration has better conditions if the refugee gets time to establish a life first! That line of thought reflects a total lack of empathy and understanding of how devastating and destructive it is for refugees to be separated. Many refugees in Denmark have been unable to learn Danish or work because they have been sleepless every night worrying about the safety of their children and spouses.

The new ruling forces Denmark and several other countries to adjust the national legislation, but it doesn’t specify exactly how long a waiting period can be accepted. So far, Mattias Tesfaye is awaiting an interpretation of the ruling from the state’s legal experts.

As a member you make it possible for us

to work on principal cases such as this