EDITORIAL: A solution model for refugees in EU

Distribution has to be based on uniform assessments and rights

Photo: Le Lykke Nielsen / 3,000 safety vests on Lesbos

Dams

All EU countries have to face the reality, and realize that refugees have come to stay, and that more will arrive in the years to come. No matter how many Frontex can keep out, many will keep coming. It is no use to put up border control and tighten the asylum rules in the individual member states. This will work like dams, only pushing around refugees internally. In the end, when everybody has built fences, the majority will end up in Italy and Greece. The two countries are already close to being bankrupt and have a massive unemployment problem. An even larger amount of refugees could make them collapse, and this will be expensive for the whole EU, maybe even make the whole union break up. The Dublin convention had this imbalance for many years, which has now become crystal clear. Besides, Europe cannot afford on a moral level to continue the scare-away tactic. We have to find durable solutions.

The amount

The number of new refugees is not a huge problem in itself – the problem is the uneven distribution within EU on short term. Almost all the refugees are now arriving in a few countries: Germany, Hungary and Sweden at the top. Denmark and Norway are also receiving a reasonably high amounts compared to the size of our populations, but we have strong economies.

If the one million refugees who arrived to Europe from outside (not counting the many refugees from Balkan who are a socio-economic problem) were more evenly distributed among EU's 503 mio inhabitants, it would not be a problem. Try telling a headmaster at a Danish public school with 500 pupils that the school will have to receive one more pupil a year, and see if she reacts with panic and strong worries about the culture and future of the school?

Expense or income

Temporary accommodation and case handling is expensive, if done in a reasonably decent manner. If many are granted asylum, expenses during the following years will include housing, health, interpreters, education – and often some kind of social allowance until the newcomers are able to support themselves.

On a longer time perspective, refugees are not necessarily an expense. On the contrary, they can be turned to an income for a Europe with dropping birth rates and a rising need for labour. But this requires that Europe invests right from the start in turning them into active citizens, building on the resources that they bring with them. It also requires that we make changes in our Scandinavian society model, which in some ways is no longer a welfare system but a bureaucratic and client creating monster. Maybe that would also benefit ourselves?

It also requires a different attitude. In Denmark, we found out long ago that a child will give the best performance when given love, comfort and appreciation. But nonetheless, we meet new citizens with suspicion, punishment and a message that they are not wanted here – and then we blame them for not being successful in our society.

Distribution

Until now, different models for distribution of refugees within EU have been discussed, and an agreement for the first 160,000 has even been reached. But only a few hundred have actually been resettled so far – it is not working. There are two reasons why not.

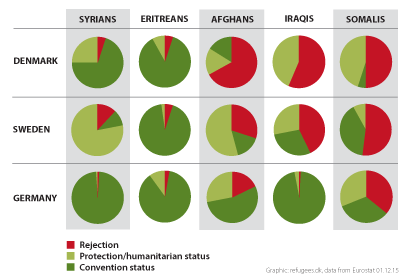

Firstly, it is hard to see how a distribution could be fair without at the same time agreeing on some kind of uniform assessment of the asylum cases. As the graph below shows, the differences right now are enormous when looking at which outcome an asylum case will have internally among the European countries (read more about the graph here). Each state has its own legal procedure, its own practice developed over the years and its own, changing political climate on top. To obtain a more uniform line of assessments, the European Asylum Agency EASO should determine the general line in the asylum decisions. The national asylum offices (Immigration Service in Denmark and similar in other countries) could handle the cases locally and take the decisions in the first instance, under guidance from EASO, and an independent European court could take care of appeals. This way, refugees would have almost the same chance in different EU countries.

asylum decisions (first instance) 3. quarter 2015

Secondly, there are too big differences between a refugee's future life situation in for instance Poland, Sweden and France. Rules for family reunification and permanent residence permit are very different, and the same goes for rights to allowances, health, education – and the actual access to the labour market. On rights, minimum standards could be introduced, as EU has already started to do (Denmark is outside these). Economically it would be possible to give the receiving country compensation per refugee the first couple of years, just like the Danish state reimburses the municipalities to some extent.

EU could be inspired by the Danish model of forced allocation between the municipalities, which as a principle works well. Parameters could be how many refugees came last year, how high is BNP, how is the employment rate, how many empty houses, has the state faced any special situations lately? An option to swop refugees could also be introduced, allowing refugees to move to another member state if they wish to, for instance because of family members which is one of the main factors for choice of country.

It may seem like a big task, but as EU has succeeded in introducing farm subsidies, common customs rules and free movement of labour, it ought to be possible to allocate 1 refugee pr 500 EU citizens per year in a way that would be acceptable by most. But we don't have much time.

For Denmark it will necessary to take part of a common asylum policy, and we will most likely get fewer than now. It will also make it easier to prepare for the arrivals, and an immense amount of time and energy will be released to discuss other important issues like transition to sustainability.