Denmark is failing resettlement refugees

Despite a rising global need and historically low numbers for new arrivals, the Danish state refuses to accept responsibility

In 2015, the then government decided to stop the agreement to receive 500 refugees via the UN resettlement programme per year, also called quota refugees. An agreement which went all the way back to 1979. The reason was the relatively large number of spontaneous refugees who arrived in 2015, i.e. those who find their way by themselves via dangerous routes. However, Denmark was the only country in Europe that introduced a stop – Sweden and Norway, on the contrary, raised their quotas during that period.

Since the decision to accept a small yearly quota again, the narrow criteria have strained the selection, and in January 2024 the full quota for 2021 has not yet arrived.

Avoiding the asylum system

Quota refugees have already had their identity and asylum needs assessed by UNHCR, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. There is therefore no doubt that they are refugees, and UNHCR has assessed that these particular persons cannot in the foreseeable future (perhaps never) return safely to their home country, and are therefore in need of permanent resettlement in another country. Juridically they are granted a permit under section 8 of the Danish Alien Act, with either protection or convention status.

When Denmark has agreed with UNHCR on which countries to receive this year's quota from, a small group of case managers from the Danish Immigration Service and the DRC Danish Refugee Council travel to those countries and briefly interview the selected in person with the use of interpreters. The refugees also get some information about Denmark in advance, and can decline the offer.

The municipalities in Denmark are informed in good time that they will receive a number of quota refugees, and both local authorities and civil society can prepare themselves for the special circumstances of this group. The refugees can also be placed in a few municipalities rather than spreading them over many, thereby gathering knowledge and creating networks.

Quota refugees arrive safely directly at their new home, and do not have to spend a long and uncertain waiting period in the Danish asylum centres. On the other hand, it can be overwhelming for them to arrive directly in Danish everyday life, which is extremely different from everyday life in a UN refugee camp somewhere outside of Europe.

Tent camp on the Greek island of Chios, photo Frederik Scheuer 2020

How many have arrived in Denmark?

Denmark has received quota refugees since 1979, but they made up only 12% of all the refugees who were granted asylum in Denmark in the 10-year period before the stop was adopted. Shortly after the stop, in the spring of 2016, the number of spontaneous refugees fell drastically, and has been historically low ever since. But it wasn't until 2020 that the Danish government decided to open quota refugees again – but only 200 per year so far. However, the narrow criteria for which refugees would be accepted proved to be such a big challenge that it has not even succeeded in meeting the small quota.

The system always contains a backlog, as you rarely manage to accept the entire quota before the end of the year. But at the moment we are so far behind that some of those who were on the 2021 quota and were selected in May 2022 will not arrive in Denmark until the spring of 2024. No one from the 2022 quota has entered yet.

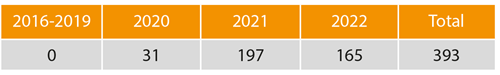

All in all, a total of only 393 quota refugees have thus entered in the course of 8 years.

The table below counts a total of 393, but should have been closer to 600 (200 per year x 3). These figures come from the Danish Immigration Service's annual Figures & Facts reports, and do not agree with figures from the UNCHR (see next table), which may be due to different calculation methods.

Number of received quota refugees according to the Danish Immigration Service

The narrow criteria

The problem with meeting the quotas is that the Danish ministry has set some special criteria since 2020: it must only be single women with or without children from the DR Congo plus LGBT people, and they must be taken from the camps in Rwanda. But this is difficult to handle for UNHCR, as they do not have that type of information on their lists and therefore have to handpick each one. However, the responsible minister Kaare Dybvad Bek has just decided that the 2023 quota can also be obtained from Afghans and Eritreans who have fled to their neighbouring countries, but it still has to be single women, children and LGBT people.

In the past, UNHCR was consulted to choose those with the greatest need to be resettled, and Denmark accepted a certain number with special needs for care and treatment. But in 2005, the Danish government introduced a requirement for "integration potential", which in practice often excludes particularly vulnerable, sick and illiterate people. The requirement for integration potential remains, but is somewhat at odds with the selected group of people these years: many of the women from the DR Congo have lived in the Rwandan camps all their lives, have very little schooling behind them and only speak the small language of Kinyarwanda. In addition, they have sole responsibility for a group of children. It is not an easy starting point for meeting the official main goals for successful integration: learning fluent Danish and getting a full-time job. Read about the DRC's and the municipalities' experiences with the first group of women from Rwanda.

The so-called integration potential has had an influence on which countries have been chosen to pick Denmark's quotas from. The choice of Rwanda is very likely connected with the plan to move the entire Danish asylum system to Rwanda. But the fact that these are refugees with a Christian background may also have played a role.

In 2001-2002, 84% of the quota refugees came from Afghanistan, Sudan and Iraq, and the majority were therefore Muslims. In 2006-2007, the share of Muslim quota refugees fell to 11%, and after 2005 Christian refugees from Myanmar and DR Congo were among the chosen ones.

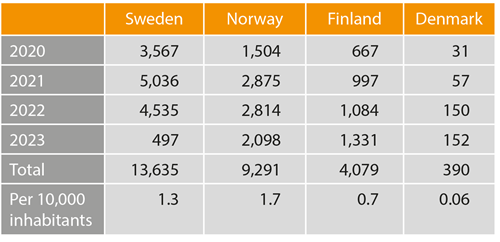

Denmark is at the bottom of the Nordic region

When the stop was introduced in 2015, Denmark received 0.09 quota refugees per 1,000 inhabitants, and was thus the country in the Nordics that took the fewest in relation to the number of inhabitants. The figure for Norway was 0.43, Sweden was 0.19 and Finland 0.18. At the same time, the number of spontaneous refugees was also lower for Denmark per capita than for the other Nordic countries, and the number has dropped sharply in Denmark since then. Denmark is now in 24th place in the EU measured per inhabitant.

Number of received quota refugees according to UNHCR:

Efficient system, but far too few recipients

The refugee resettlement system itself is often and rightly highlighted as one of the most important and best solutions to the global challenge of housing refugees. However, UNHCR itself points out that the system cannot stand alone and cannot replace spontaneous asylum applications. Alternative forms of entry such as humanitarian visas, sponsorship programs, family reunification and work permits also contribute to securing a future for refugees. However, a large-scale and effective expansion of the quota system is the most obvious improvement in view. And it would undoubtedly reduce the number of people who embarked on life-threatening journeys via deserts, mountains and seas.

Some of the benefits are:

- Relief from overburdened nearby areas and neighboring countries, where approx. 80% are located today

- Long, dangerous journeys with smugglers can be replaced by safe and legal transport

- The receiving country can prepare both itself and the applicants for arrival

- Special needs and vulnerable people can be prioritized

However, need and demand are in stark contrast today, and it is getting worse year by year. Less than one percent of the world's refugees are resettled. Only 18 countries in the world, 13 of which are in Europe, have committed to receiving a fixed annual quota, and the total number represents only a fraction of those identified by UNHCR as in need of resettlement.

In 2023, only 3,737 refugees were resettled among the 2 million that UNHCR had selected from the total of approx. 110 million displaced and approx. 36 million refugees worldwide.

The USA topped by receiving 1,677 quota refugees, but in comparison there are approx. 6.6 million in temporary camps in the world. In Cox's Bazar in Bangladesh alone, there are approx. 600,000. Seen in that light, it seems absurd that Denmark's quota is counted in a few hundreds.

Profile of quota refugees that UNHCR resettled in 2023 (3,737 in total):

- Top 5 countries of residence: Turkey, Malaysia, Lebanon, Ethiopia, Iran

- Top 5 nationalities: Syria, Myanmar, DR Congo, Afghanistan, Eritrea

- Top 5 recipient countries: USA, Canada, Germany, France, New Zealand

UNHCR estimates that the need for resettlement will increase by 20% to 2.4 million in 2024. At the same time, an increasing proportion of them have an urgent need for treatment of life-threatening diseases, as fewer and fewer recipient countries will accept them – including Denmark. Source for the above mentioned numbers: UNHCR.

Danish hypocrisy

Danish politicians from many different parties have long talked about the asylum system being "broken" and that Europe must destroy the smugglers' business model in order to avoid the many deaths in the Mediterranean. There is also a lot of talk about helping in the neighbouring areas rather than letting the refugees come up here, and that the current system favours the strongest.

All of this appears to be the highest degree of hypocrisy, only intended to win Danish voters, seen in the light of the fact that Denmark has in practice done the exact opposite by receiving an ever smaller number of quota refugees. At the same time, successive Danish governments have actively undermined the entire foundation for resettlement, which is a lasting solution. This has been done with the many restrictions on access to permanent residence and citizenship and finally with the 'paradigm shift' in 2019, after which even quota refugees only get a permit "with the aim of temporary residence", and in principle can lose it again.

“It offers individuals and families a unique and meaningful chance to rebuild their lives in an environment where their rights are protected from day one, and where access to naturalization and citizenship promise an end to years of displacement.”

– UNHCR about the resettlement programme

The case of the Bhutanese refugees, which we described recently, clearly illustrates that Denmark does not live up to its responsibility and does not recognize the premise of resettlement, when even stateless quota refugees are still in temporary residence after 15 years and do not have a real chance in order to obtain the Danish citizenship they were promised.

Did this article give you useful information?

Become a member today

and support our future work